And, behold, the archangel Michael rolled back the stone from the door of the tomb; and the Lord said: Arise, my beloved and my nearest relation; thou who hast not put on corruption by intercourse with man, suffer not destruction of the body in the sepulchre. And immediately Mary rose from the tomb, and blessed the Lord … And kissing her, the Lord went back, and delivered her soul to the angels, that they should carry it into paradise.

I have been reading some alternative gospels that in their day were enormously influential, but have since largely fallen into undeserved oblivion. In terms of understanding Christian history, they are enormously important. In this particular case, though, I need to offer a rationale as to why they merit that attention!

The passage above is from a fifth century text called The Passing of Blessed Mary, De Transitu Virginis. Its date is misleading, as it was by no means the first work to present the passing or death of the Virgin Mary in terms very close to that of Christ himself. Such stories were circulating from the third and fourth centuries, and were reported in a series of works like the Liber Requiei Mariae (The Book of Mary’s Repose) and the Six Books Apocryphon, which today survive in Syriac or Ethiopic, and the account of the Dormition credited to John the Evangelist. The De Transitu was so important because many of its predecessors were associated with heretical opinions, and this tried to reclaim this Mary tradition for orthodoxy. Also, the work’s translation into Latin meant that it would be easily available to the regions that would become central to the faith in the Middle Ages.

All these works recount a similar body of stories. After the Crucifixion, Mary devotes herself to the new church, but one day she receives an angelic visitation that recalls the original Annunciation. Knowing she is to die, she asks that the apostles be gathered from the corners of the world, and they duly appear. They accompany her at her death and join the funeral procession, which is marked by various miracles, mainly directed against the evil Jewish authorities. Christ appeared to take Mary’s soul to heavenly glory.

Throughout the various works, the analogies to the canonical stories of Christ are frequent and explicit. Apart from the second Annunciation, she features in a new Pentecost, a new entry into Jerusalem and, most spectacularly, her own Resurrection. These works are, very clearly, alternative gospels starring Mary. They are also substantial pieces: in English translation, the Six Books Apocryphon alone runs to some twelve thousand words.

As the core story was passed on, it acquired even more miracles, and still closer analogies to Christ’s experience. According to one widespread medieval legend, all the apostles gathered to witness Mary’s ascension to glory, except for Thomas (who was also inconveniently late for Christ’s Resurrection appearance). Mary, however, generously appeared to him personally, and as a token of proof left her Girdle or Belt, which became a famous relic. The scene was much used in Renaissance art, and it appears in the Golden Legend.

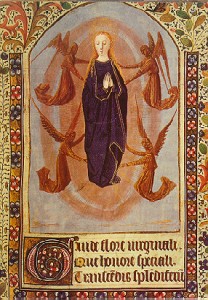

This literature had an enormous impact in giving pseudo-scriptural foundation to the very widely held church doctrine of Mary’s Assumption or Dormition. Assumption is the Western and Catholic term, suggesting that she was taken to heaven prior to death; the Orthodox accept Dormition, namely that after her bodily death, her body was raised as the first sign of the general Resurrection. Whichever version we consider though, these ideas were very widespread in Christian art through the Middle Ages and the Renaissance era, and shaped the Eastern icon tradition.

At least in official doctrines, those ideas are still, today, firmly held by the Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches – think of perhaps two-thirds of the world’s Christians. As recently as 1950, Pope Pius XII stated that “we pronounce, declare, and define it to be a divinely revealed dogma: that the Immaculate Mother of God, the ever Virgin Mary, having completed the course of her earthly life, was assumed body and soul into heavenly glory.” Catholic and Orthodox alike mark the date of the Assumption, August 15, as a great feast of the church.

Given the later impact of those ideas, we might think that works like the De Transitu would be worth intense study, especially given the fascination with ancient apocryphal and alternative gospels. Oddly, though, they have been badly understudied, even in the standard works on New Testament Apocrypha. (The great exception is the work of Stephen J. Shoemaker, in books like The Ancient Traditions of the Virgin Mary’s Dormition and Assumption, 2002).

One reason for this, of course, is that for most Protestants (and some Catholics), the ideas I am describing – the whole Marian lore – is so bizarre, so outré, so sentimental, and so blatantly superstitious that it just does not belong within the proper study of Christianity. If anything, it’s actively anti-Christian. Even scholars prepared to wrestle with the intricacies of Gnostic cosmic mythology throw up their hands at what they consider a farrago of medieval nonsense.

As I’ll argue in a forthcoming post, that response is profoundly mistaken. If we don’t understand devotion to Mary, together with such specifics as the Assumption, we are missing a very large portion of the Christian experience throughout history. It’s not “just medieval,” any more than it is a trivial or superstitious accretion.

By the way, September 8 is celebrated in Catholic countries around the world as the feast of Mary’s Nativity. For a few hundred million fellow-Christians, that’s an important date.