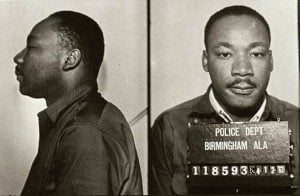

We who engage in nonviolent direct action are not the creators of tension. We merely bring to the surface the hidden tension that is already alive. We bring it out in the open, where it can be seen and dealt with. ~Martin Luther King, Jr.

When Martin Luther King, Jr. first drafted those now-famous in his Letter from Birmingham Jail, white and black Christians throughout the South were holding separate church services on Easter Sunday, 1963. While the celebration of the risen Christ should have united all Christians, like all other Sundays, it only served to highlight the distance between them throughout the American South. As King articulated, the direct action campaign of the SCLC and ACMHR did not cause this conflict between whites and blacks, but merely brought that conflict out into the open for the nation to see. Likewise, the legal wranglings over the closing of the Nashville Christian Institute (NCI) in 1967 did not cause conflict between African American and white Church of Christ leaders, but merely brought that submerged conflict to the surface.

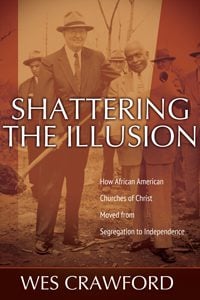

In Shattering the Illusion, Wes Crawford tells the story of how, in the wake of the conflict over NCI, African American Church of Christ leaders forged their way towards independence. (More on that here.) Crawford tells that story well, bringing to life African American Church of Christ leaders like Marshall Keeble, G.P. Holt, R.N. Hogan, G.P. Bowser, and Jack Evans. Little known even in most white Stone-Campbell circles, their stories have appeal beyond their particular denominational context for Crawford has answered the the “so what?” question well. He demonstrates that, although replete with particularities, the story of “how African American Churches of Christ moved from segregation to independence” is the story of American Christianity writ small.

On a small scale, the story of African American Churches of Christ demonstrates the manner in which race dominantly shaped Christianity in America. The same sequence of events that Crawford recounts took place (or had already taken place) in denominations across the country. In the first half of the twentieth century both African American and white churches of Christ were committed to a patternistic approach to the New Testament and a restorationist understanding of the church. Further, they both employed the Campbellite tripartite formula (158-9) of hermeneutics. And yet, agreement on these ostensibly first-order issues–as well as many more–could not bridge the racial gap. Thus, instead of embodying the unity that birthed the Stone-Campbell movement, they demonstrated a true maxim in America: race trumps religion.

On a small scale, the story of African American Churches of Christ demonstrates the manner in which race dominantly shaped Christianity in America. The same sequence of events that Crawford recounts took place (or had already taken place) in denominations across the country. In the first half of the twentieth century both African American and white churches of Christ were committed to a patternistic approach to the New Testament and a restorationist understanding of the church. Further, they both employed the Campbellite tripartite formula (158-9) of hermeneutics. And yet, agreement on these ostensibly first-order issues–as well as many more–could not bridge the racial gap. Thus, instead of embodying the unity that birthed the Stone-Campbell movement, they demonstrated a true maxim in America: race trumps religion.

As the hubbub over NCI unfolded and the courts ruled in favor of the white board of directors, the hidden resentment of African American Church of Christ members due to years of white paternalism came to the surface. That event shattered the illusion of racial unity, and African American and white Churches of Christ diverged sharply. As a result, over time their theologies diverged as well. Black Churches of Christ maintained a more traditional Stone-Campbell hermeneutic, even as white Churches of Christ embraced a hermeneutical shift. Unfortunately, this reality “reinforced the separation that the Civil Rights Movement precipitated (175).” As a result, as white leaders in the Church of Christ movement pursued racial reconciliation in the late twentieth century, they ironically found that theology as much as race, now separated them–a trend observable in almost every American denomination. First, race separated coreligionists. Second, separated by race, coreligionists developed differing theologies. Thus, through racism, blacks and whites were twice divided. Whether that divide remains too large to bridge has yet to be determined. Likely, the answer to that will be determined on a denomination-by-denomination or movement-by-movement basis. For Churches of Christ, Crawford seems cautiously optimistic.

Throughout Shattering the Illusion, Crawford also exhibits nuance of interpretation as it relates to African American religious history. For example, in recounting the story of Marshall Keeble, he demonstrates the manner in which the accommodation-protest rubric simplistically dichotomizes African American responses to a white dominated society. Although deferential to white leaders in the Church of Christ, Keeble did not accept the racial status quo. Rather, during his long career, he worked within the system in order, raising money to support African American education, a cause critical to long-term African American advancement. As a result, even while his deference gave white leaders the “illusion” of racial harmony, it also allowed a great many African American young men, including Fred Gray, to attend school. Fred Gray later became a Civil Rights attorney, working alongside Martin Luther King, Jr. and E. D. Nixon. In Crawford’s telling, without the “accommodation” of Keeble, the “protest” of Gray would not have been possible. Each worked in a particular way, and in a particular time, but both worked towards the same goal: the improvement of African Americans’ place in society.

A short read at 182 pages of text, an evening with Shattering the Illusion would be well-spent. Aside from what it reveals about Churches of Christ, it illuminates much regarding the manner in which race has shaped religion in America, dividing virtually every denomination. When you read it, read it with that in mind.