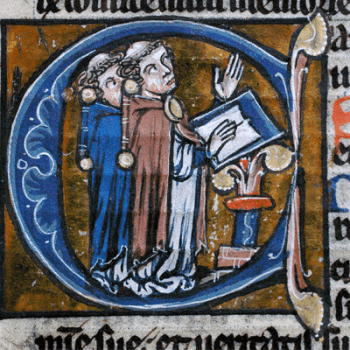

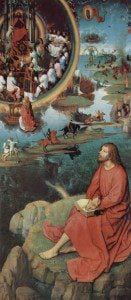

A man named John found himself “on the island called Patmos on account of the word of God and the testimony of Jesus.” While “in the Spirit on the Lord’s day,” he heard a loud voice instruct him to “write what you see in a book and send it to the seven churches.” Presumably, like many ancient Israelite prophets, John receives his visions while in a trance or some state of altered consciousness. What John saw and wrote has become the most influential — and controversial — vision in the history of Christianity. As Elaine Pagels observes in her Revelations, John’s apocalypse has served as source material for John Milton, Julia Ward Howe, Michelangelo, and Tim LaHaye. At the same time, as late as the early 1500s Martin Luther wanted to remove Revelation (and the Book of Jude) from the New Testament canon, though the reformer subsequently changed his mind.

A few basics:

▪ Based on differences of both language and theology, scholars do not connect John of Patmos with either the Gospel of John or the Johannine epistles. In contrast to that of John’s gospel, New Testament scholar Dale Martin terms the Greek in the Book of Revelation “atrocious, seeming almost illiterate at times.” Unlike the Book of Revelation, moreover, neither the gospel nor those epistles identify their authors.

▪ The book presents itself as “the apocalypse of Jesus Christ.” One might think of it as Jesus Christ’s unveiling or uncovering of both the present and the future.

▪ The Book of Revelation consists of a series of visions, centered around theophanies of Jesus Christ and visions of judgment and warfare between God and Satan. Before he receives any instructions about what he should write, John sees “one like a son of man” arrayed in glory. After John writes the epistles to the seven churches, he receives a marvelous vision of the heavenly throne and sees “a Lamb standing, as though it had been slain.” In the book’s nineteenth chapter, John sees heaven open and he sees a rider on a white horse, “clad in a robe dipped in blood.” This figure, coming to smite and rule the nations, is the “King of kings and Lord of lords.” After Jesus Christ’s armies defeat those of the beast, Satan is bound in hell for a thousand years. In a “first resurrection,” martyrs come to life and enjoy a millennial reign with Christ. After the thousand years, Satan is briefly loosed but suffers a final defeat. All of the remaining dead stand before Christ’s throne, judged “by what they had done.” Those whose names are not found in the book of life are cast into the lake of fire. Finally, John sees a “new heaven and a new earth,” and a holy city “new Jerusalem” comes down from heaven. God will dwell with resurrected and redeemed men and women, who will no longer experience pain or death. Instead, they shall worship God and Jesus Christ. In fact, they will see God’s face.

Now, if I could explain exactly what the above means for our immediate futures, or if I were even willing to take an impassioned stab at it (Vladimir Putin as new candidate for “anti-Christ,” a term which, by the way, only appears in the Johannine epistles, not as many presume in the Book of Revelation), I could author much better-selling books.

In the meantime, it might be fruitful to examine what sort of believer John of Patmos might have been and how early Christians would have understood his apocalypse. To this end, I’m relying on Elaine Pagels’s Revelations and Dale Martin’s New Testament History and Literature.

Pagels suggests that John is among the second generation of Christian believers, beginning to write around the year 90, around two decades after the failed Jewish revolt against Rome. The Book of Revelation brims with anger against Rome and perhaps against the Emperor Nero, whose name in Hebrew might be the meaning behind the mark of the beast being 666. Again according to Pagels, though, John writes not only “against the Romans but also against members of God’s people who accommodated them and who, John suggests, become accomplices in evil.” Although the “multivalent” symbolic language of the book has lent itself to a host of interpretations, Pagels (and most other scholars) believe that John wrote first and foremost about the situation in which he found himself, not events in a distant future (or our present). She understands a chasm between prophets such as John and the Gentile followers of Paul and his allies, who were steering the early church in a very new direction. John warns his followers against those who “say they are Jews, and are not.” These Christians ate meat sacrificed to idols and, John alleges, practice fornication. The former point is a rather different perspective than Paul’s. As Martin puts it, John condemns “comfortable Christians” who conform too much to the pagan standards of the Roman empire. True followers of Christ might encounter persecution from Rome, but they will triumph in the end. “For those slaves of Christ who suffer in poverty and patience,” writes Martin, “stoutly resisting Rome and their wealthy, idolatrous neighbors, the bloody, horned Lamb will finally bring salvation, happiness, and peace, a city better than Rome, a new Jerusalem.”

John’s vision of Jesus Christ led future generations of Christians to understand their Savior as — among many other New Testament images — the coming king, the lamb who was slain who becomes Satan’s vanquisher and who establishes a millennial reign on earth. The Book of Revelation is the only New Testament writing to present the idea of the saints reigning with Christ for “a thousand years,” an incredibly influential idea within the subsequent development of Christian eschatology. John also led many Christian visionaries and prophets to both replicate and appropriate his words and imagery, shaping the way that countless men and women saw and heard Jesus Christ. Like John, many of those visionaries believed that their contemporaries were too “comfortable” and needed to be awoken to a more pure and fervent devotion to their Savior.

Pagels also observes that John lived at a time of competition among Christian/Jewish prophets. He denounces a prophet named Jezebel and a man he calls Balaam. John apparently was one of a good many traveling prophets, many of whom taxed local Jewish and Christian communities for financial support. Indeed, there were early Christian bishops such as Ignatius of Antioch who emphasized the authority of bishops above that of prophets. By the end of the first century, there were already fault lines within early Christianity over the desirability or permissibility of prophecy, visions, and revelations. Those debates, of course, have persisted throughout the entire course of Christian history without ever reaching resolution.