The Roman Pantheon is awesome. And I mean “awesome” in the sense that my good-English-professor-friend would approve: it evokes feelings of awe and wonder.

I caught my first glimpse of this 2000 year-old building after stepping from a stone-paved street into the Piazza della Rotonda. We were on our way back from the Roman Forum and, I confess, I was actually looking for a coffee shop (the Sant’ Eustachioe, if you are interested). Suddenly my son stopped and said, “Mom. Look.”

I caught my first glimpse of this 2000 year-old building after stepping from a stone-paved street into the Piazza della Rotonda. We were on our way back from the Roman Forum and, I confess, I was actually looking for a coffee shop (the Sant’ Eustachioe, if you are interested). Suddenly my son stopped and said, “Mom. Look.”

I did.

My husband was already taking pictures.

The magnificent porch of the building loomed in front of us, still looking virtually as it had when completed around 125 A.D. by the Roman emperor Hadrian. Because the original Pantheon (which had burned down in 80 A.D.) had been commissioned by Marcus Agrippa (son-in-law of Augustus Caesar), Hadrian dedicated the 2nd century construction to Agrippa: as the porch inscription reads, “M. AGRIPPA L.F. COS TERTIUM FECIT” or “Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, consul for the third time, made this.”

Attached to the awe-inspiring porch, of course, is the even  more awe-inspiring rotunda. The original Pantheon was designed as a typical rectangle temple. Not so the 2nd century building. It is an engineering marvel–boasting a circular dome that, at 142 feet high, was the world’s largest dome until the fifteenth century. It still (despite its age) is the world’s largest unreinforced concrete dome, as multiple Roman tourist sites love to tell.

more awe-inspiring rotunda. The original Pantheon was designed as a typical rectangle temple. Not so the 2nd century building. It is an engineering marvel–boasting a circular dome that, at 142 feet high, was the world’s largest dome until the fifteenth century. It still (despite its age) is the world’s largest unreinforced concrete dome, as multiple Roman tourist sites love to tell.

An incongruity, however, caught my son’s eye. He wanted to know why there was a cross on top of the ancient Egyptian obelisk standing in front of the Roman Pantheon.

Indeed, it is the question of this post–did early medieval Christians accommodate paganism? The Pantheon certainly suggests so, as in 609 A.D. it was converted into the Church Sancta Maria ad Martyrs.

So, yes, early medieval Christians did indeed accommodate paganism, at least to the point of repurposing a significant pagan building as a place for Christian worship.

But because they transformed pagan temples into churches, does that mean early medieval Christians also accommodated pagan festivals and holidays? This seems to be the common understanding, just check out paganmegan’s comment on my first Easter post and even the description of early medieval Christian missionary efforts on sites like http://mythsofchristianity.com/easter.

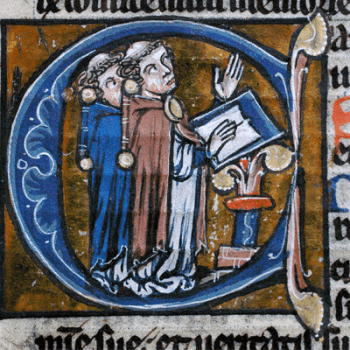

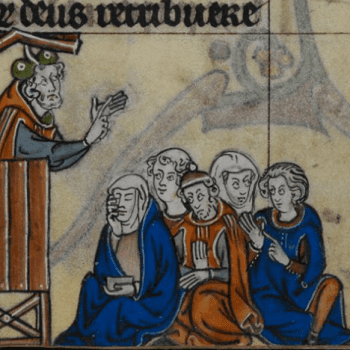

Let’s look at the source which begins most discussions (both scholarly and amateur) about early Christian accommodations of paganism. It is a letter that Gregory the Great, Bishop of Rome, wrote to the French abbot Mellitus in 601 A.D. Mellitus was then to relay the letter to Augustine of Canterbury, Gregory’s lead Bendictine missionary to East Anglia. This is what Gregory wrote:

But when Almighty God shall have brought you to our most reverend brother the bishop Augustine, tell him that I have long been considering with myself about the case of the Angli; to wit, that the temples of idols in that nation should not be destroyed, but that the idols themselves that are in them should be. Let blessed water be prepared, and sprinkled in these temples, and altars constructed, and relics deposited, since, if these same temples are well built, it is needful that they should be transferred from the worship of idols to the service of the true God; that, when the people themselves see that these temples are not destroyed, they may put away error from their heart, and knowing and adoring the true God, may have recourse with the more familiarity to the places they have been accustomed to. And, since they are wont to kill many oxen in sacrifice to demons, they should also have some solemnity of this kind in a changed form so that on the day of dedication, or on the anniversaries of the holy martyrs whose relics are deposited there, they may make for themselves tents of the branches of trees around these temples that have been changed into churches, and celebrate the solemnity with religious feasts. Nor let them any longer sacrifice animals to the devil, but slay animals to the praise of God for their own eating, and return thanks to the Giver of all for their fullness…For it is undoubtedly impossible to cut away everything at once from hard hearts, since one who strives to ascend to the highest place must needs rise by steps or paces, and not by leaps. (http://legacy.fordham.edu/Halsall/source/greg1a.asp; http://legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/source/bede1.asp for Bede’s account of the Anglo-Saxon conversion)

Three things stand out in this letter.

First, Gregory was writing it to a specific group of people in a specific location: the “case of the Angli” and “the temples of idols in that nation.” He is not making a pronouncement for all missionary endeavors throughout the whole of Christendom. As George Demacopoulos writes in his 2008 article, “Gregory the Great and the Pagan Shrines of Kent” (Journal of Late Antiquity), this is a “temporary accommodation for a long-term pastoral good” and “the exact prescription that was needed for the initial acceptance of the faith in Kent.” Moreover, Gregory made it clear that the buildings were to be used if they were “well built.” Gregory was acting pragmatically–why build new churches when sturdy structures already existed?

Second, as for the repurposed pagan feast, Gregory only states, “since they are wont to kill many oxen in sacrifice to demons, they should also have some solemnity of this kind in a changed form…” This is a far cry from wholesale adoption of pagan practices and celebrations. It is a suggestion about a particular custom–sacrificing cows. Of course, it is true that evidence of these sacrifices exist at medieval church sites (such as the oxen bones found at the site of St. Paul’s in London). It is also true that Gregory explicitly condemned such sacrifices for “demons,” allowing these sacrifices only for “the praise of God for their own eating.”

Finally, Gregory’s letter to Mellitus must be contextualized. Gregory the Great had a reputation as a “destroyer of pagan culture,” especially pagan idols. As Cristina Ricci has written in A Companion to Gregory the Great, “he was intolerant towards rites of pagan origin that persisted among Christians peoples.” Nor was Gregory alone. The Bishop of Rome Zacharius in a letter to Boniface 6 years later condemned “sacriligious priests who, you say, sacrificed bulls and cows and goats to heathen gods, eating the offerings of the dead, defiling their own ministry.” Likewise, in 742, Archbishop Boniface declared that all bishops should “see to it that the people of God perform not pagan rites but reject and cast out all the foulness of the heathen, such as . . . offerings of animals which foolish folk perform in the churches according to pagan custom.” (David Grummett and Rachel Muers, Theology on the Menu: Asceticism, Meat and Christian Diet, Routledge 2010). Rejection and destruction of paganism was the larger context of Gregory’s 601 letter–not blanket accommodation.

So where does this leave us?

I think the Pantheon provides our answer. It is clearly a pagan building, but it has been transformed into a Christian house of worship. Mass is still celebrated there, but it is on a Christian altar with no pagan idols in sight. In other words: of course early medieval Christians repurposed pagan sites (it was pragmatic) and of course they allowed local customs to continue that did not threaten or undermine Christianity. Indeed, Gregory’s letter to Mellitus set a precedent for how Christians could smooth the conversion process by allowing people to worship in familiar places and even in familiar ways (see the Spanish as a later example).

At the same time, we cannot forget that Gregory’s letter was specific, limited, and pragmatic. It did not permit wholesale adoption of any pagan custom. It also did not permit the “familiar” customs and places to continue worship of pagan gods (sorry, no undercover worship of Ishtar!). What it did do was use existing structures (those “well built” temples) to spread Christianity . Funny enough, as the cross in front of the Pantheon attests, this worked.