“The whole of sacred doctrine consists of two parts,” wrote John Calvin at the outset of his 1536 Institutes of the Christian Religion, “knowledge of God and of ourselves.” Likewise, in his expanded 1559 edition of the Institutes, Calvin repeated that human wisdom “consists almost entirely of two parts: the knowledge of God and of ourselves.”

Calvin’s opening paragraph in his final edition of the Institutes is beautiful. Even a quick survey of human endowments should convince us that they come from God, “that our very being is nothing else than subsistence in God alone.” Furthermore, “those blessings which unceasingly distil to us form heaven, are like streams connecting us to the fountain.” Calvin thus begins with the “infinitude of good which resides in God.”

Things quickly get less rosy, though. Later in that same opening section, Calvin writes that “ever since we were stript of the divine attire our naked shame discloses an immense series of disgraceful properties.” Looking at our “own evil things” should compel us to “consider the good things of God.” Right from the start, there’s a tension between the goodness and evil inherent in humanity, both of which Calvin believed should point human beings toward the source of infinite goodness and the ground of their being.

Calvin, the reformer whose prose both thrills and numbs, whose ideas both exhilarate and deflate. Just as Calvin found it a lifelong project to distil Christian doctrine into summary form, so for many Reformed Christians it has been a lifelong project to tease out the implications of Calvin’s ideas for their own lives, congregations, and nations.

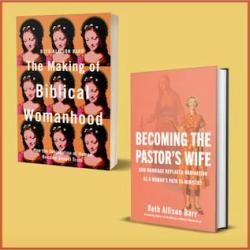

It is to this latter project that Reformation scholar Bruce Gordon turns to in his contribution to Princeton’s Lives of Great Religious Books series.

It is to this latter project that Reformation scholar Bruce Gordon turns to in his contribution to Princeton’s Lives of Great Religious Books series.

Gordon’s “biography” of the Institutes begins with the simple but crucial point that its reception has been and is inextricably linked with the broader reputations of its author and the “Calvinism” that emerged in the second half of the sixteenth century.

Following two chapters on the coming forth of the Institutes in its various editions, Gordon discusses its translation and then traces the ways that Europeans, Americans, and then eventually Christians around the world have read, ignored, understood, and reinterpreted the Institutes. Starring roles include many usual suspects, such as Schleiermacher, Warfield, Kuyper, Barth, and Brunner.

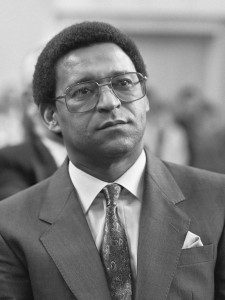

For me, the most fascinating chapter is Gordon’s account of how Calvin and Calvinism both undergirded the South African system of apartheid but also inspired some of its boldest opponents. Allan Boesak, for instance, emerged as the leader of black Reformed Christians who cited Calvin’s words that “where the glory of God is not made the end of government, it is not a legitimate government.” Furthermore, Boesak cited a passage from the institutes in which Calvin argued that because “we have been redeemed by Christ at so great a price as our redemption cost him … we should not enslave ourselves to the wicked desires of men.” Gordon uses such examples to highlight Calvin’s fundamental belief that, in Gordon’s words, “nothing in human existence, absolutely nothing, possesses a shred of authority or legitimacy apart from the will of God.” Gordon contends that the “Institutes is a thoroughly subversive work.” Oppressors have at various times found Calvin and Calvinism useful, but Gordon appropriately reminds that Calvin’s message has been a great comfort and inspiration “in times of persecution and exile, moral and political chaos, and personal tragedy.” It is a comfort to many to rest within God’s sovereignty.

Today, there are many constructions of Calvin. He is the “heritage” figure for many Reformed denominations, cited

occasionally but mostly ignored because many of those denominations have long since set aside many of his ideas. At the same time, his words provide ongoing inspiration for a range of Protestant Christians, from Neo-Calvinists like John Piper to anti-apartheid ministers and laypeople in South Africa. While Calvin has his fans, he has many detractors. “Calvin is a metaphor for everything people dislike about Christianity,” Gordon explains, “in particular its supposed intolerance and moralism.” If such detractors know anything about Calvin, they might know that he sanctioned the burning of anti-Trinitarian Michael Servetus and that he believed that God had elected the damnation of the vast majority of human beings.

Gordon explains that Calvin’s reputation has been haunted by his less desirable ideas and actions, namely his belief in double predestination and his sanctioning the execution of anti-Trinitarian heretic Michael Servetus in 1553. Indeed, Gordon’s book is a bit haunted by those things as well, especially the burning of Servetus.

First, in his discussion of original sin, Calvin observes that “even infants bring their condemnation with them from their mother’s womb, suffer not for another’s, but for their own defect. For although they have no yet produced the fruits of their own unrighteousness, they have the seed implanted in them … their whole nature is … a seed-bed of sin.” That robust sense of human depravity has been, well, a bit too total for many Protestants.

The shade of Servetus appears regularly in Gordon’s biography of the Institutes. How can we admire the writings of a man who sanctioned the burning of another at the stake?

Gordon addresses Calvin and Servetus in a brief appendix. As Gordon explains, Calvin had done his best to ignore Servetus, who wrote him extensive comments on the Institutes. When it came to executing heretics, moreover, Calvin was rather moderate. Gordon informs that he petitioned Geneva’s magistrates to merely decapitate Servetus. But Calvin did agree that Servetus deserved death. Geneva had asked other reformers, such as Melanchton and Bullinger, for their views. They agreed as well. Calvin was a willing participant in the process against Servetus, but not the prime mover. The Geneva Council controlled the affair. Had Geneva let Servetus go free, it would have confirmed to the world that the city condoned heresy. Servetus had no chance.

Gordon’s conclusion:

Why at a time when Catholics and Protestants perished at each other’s hands in great numbers has the story of Calvin and Servetus become emblematic of an intolerant age? The reasons are complex, but most significantly the opponents of the Genevan reformer, who hated his doctrine of double predestination and other aspects of the Institutes, including his insistence on a rigorous Trinitarian theology, used the printing press for slander. Calvin was quickly and effectively turned into a monster, and Servetus his victim. The Spaniard embodied those who suffered the torments of the age, the Frenchman the perpetrators. Both were cast in symbolic roles where they remained for centuries.

Calvin’s reputation and that of the Institutes will never be severed from the fate of Servetus, but Gordon suggests that the Institutes also needs liberation from “pallid articles and monographs that in their pedantry lose sight of the book’s breadth.” It has been a long while since I read the Institutes at my Presbyterian seminary (and in graduate school at Notre Dame), but my memories thoroughly agree with Gordon’s assertion that Calvin “wanted not to persuade readers of a few principles or aphorisms, to achieve mere intellectual assent, but rather to bring about transformation to the life of Christ, a goal that would end in union with Christ.” While we continue to sin, we as Christ’s followers are “engrafted onto him and live piously,” responding to God’s favor. That I understood as the heart of Calvin’s message, the end result of the proper knowledge of God and humanity.