Only one American work made the cut for Christian History magazine’s list of 25 Christian writings “that changed the church and the world”: Jonathan Edwards’ Treatise Concerning Religious Affections (1746), ranked #23. It’s hard to question the significance of a preacher whose books and sermons continue to influence Reformed and evangelical theology to this day.

But as Edwards’ most infamous grandson sings in the acclaimed musical Hamilton, “there are things that homilies and hymns won’t teach ya.”

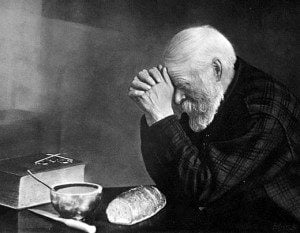

So as I continue this extended response to the CH list, I’ll look beyond both theology books and hymns to consider a type of Christian writing that is as prevalent as it is short: the table grace.

* * * * *

Now, written prayers do show up in the CH list. The Book of Common Prayer is #12, and Augustine’s top-ranked spiritual autobiography is famously addressed to God.

But what I have in mind are brief prayers that were once written, but live on less in published form than in oral tradition. In evangelicalism, for example, it’s hard to overstate the importance of “the sinner’s prayer,” whose history Tommy Kidd once shared at this blog. While it originated with Puritans and Great Awakening evangelicals, he thought that the

terminology of “receiving Christ into your heart” became more formalized as a non-Christian’s prayer of conversion during the great missionary movement of the nineteenth century. The terminology became a useful way to explain to proselytes that they needed to make a personal decision to follow Christ.

While I was visiting a Baptist church this summer, I heard the pastor semi-jokingly remind his congregation that a prayer that “asks Jesus into your heart” is not actually found in the New Testament. Or as “the evangelical Onion” put it recently:

Bible Lacking Sinner’s Prayer Returned For Full Refund https://t.co/7dkg6lQr8p pic.twitter.com/ufxfJU1mV0

— The Babylon Bee (@TheBabylonBee) August 16, 2016

But apart from the Lord’s Prayer, I don’t think any Christian writing has been prayed as often as the various “table graces.” If I were Catholic or knew that tradition’s history better, I’d write about “Bless us, O Lord, and these Thy gifts, which we are about to receive from Thy bounty, through Christ our Lord.” But I’m a pietistic Midwestern Protestant, so as long as I can remember, I’ve prayed the same table grace my wife and I have now taught our children:

Come, Lord Jesus, be our guest

And let these gifts to us be blessed

Amen

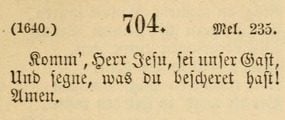

There’s some intra-family debate on my wife’s side about the second line — a dissident faction prefers “And let our daily bread be blessed.” And my mother-in-law grew up in a household that used the original German version:

Komm’, Herr Jesus, sei unser Gast

Und segne, was Du uns bescherret hast [And bless what you have bestowed on us]

Amen

But in any case, it seems that the prayer was first printed in 1753, in a Moravian hymnal published in London. Some attribute authorship to Nicolaus von Zinzendorf, but a supplement to a Missouri Synod hymnal notes that “Komm’, Herr Jesu” was originally placed among “evangelical hymns from the seventeenth century.” (Some have even tried to attach the prayer to Luther, who suggested his own mealtime prayers in the Small Catechism.)

In any case, while it remains in common use among Moravians, “Come, Lord Jesus” soon spread to other Protestant traditions. On my wife’s side, it came down from both branches of the family tree: one Scandinavian Lutheran, the other German Reformed. On my side, it goes back (in English) as far as my mom’s grandmother, who grew up Augustana Lutheran. But it’s also very common in the Evangelical Covenant Church, whose founders refused to join their more confessional counterparts in the Augustana Synod. And I’m sure many of you from other denominations and traditions have prayed it as well.

So what’s so important about these fifteen words? How has it changed the church, and perhaps the world?

First, it reminds us that Christian faith is not purely intellectual or other-worldly; it is incarnate, inseparable from the body’s physical needs.

Second, it reminds us that Christian faith is not individualistic; it is inseparable from our relationships, with Jesus and with his other followers. For me, this prayer especially drives home the realization that my faith is bound up with my family; it helps me remember that I know Jesus Christ not only by personal decision but because my parents and their parents and generations more knew him first.

May it be so with our children and their children as well! If Lutheran theologian Carl Braaten was right that Christianity is always “only a generation away from possible extinction” — meaning that it can’t be sustained in the form of buildings, books, or institutions, only through living faith passed on from one witness to another — then “Come, Lord Jesus” joins bedtime prayers and other seemingly simple liturgies in keeping alive a story that will be forgotten if it’s not shared.

In a 2009 Patheos post, another Lutheran scholar, Gene Veith, complained about the simplicity of this table grace: “It seems, well, childish, and, with its sing-song rhyme, more like a nursery rhyme.” But some of his readers insisted that it was important precisely because it was accessible to children:

It relates to everyone no matter how old or their religious background….

I like the Common Table prayer for large gatherings because you CAN use it in unison, and have everyone, including small children, participate.

(Likewise, Tommy observed that the “there was a major uptick in the use of the actual phrase ‘ask Jesus into your heart’ in the 1970s, perhaps as children’s ministry became more formalized and leaders looked for very simple ways to explain to children what a decision for Christ would entail.”)

In short, it’s a way of living out in our own context Jesus’ invitation: “Let the children come to me, and do not stop them; for it is to such as these that the kingdom of heaven belongs.”

Of course, in the five hunger-hurried seconds it takes our family to say this prayer, I’m not sure we reflect consciously on its theological claims. (“What does ‘Come, Lord Jesus’ mean?”, I asked the kids earlier this year. “I dunno,” the twins replied, as one.)

But just because our minds don’t do the theological work in that instant, it doesn’t mean that the prayer isn’t sinking in. For better and for worse…

“Come, Lord Jesus, be our guest”: Part of me wonders if praying these words over suburban meal after suburban meal hasn’t made too safe what’s actually a political, eschatological, apocalyptic call for justice. (“Come, Lord Jesus” ought to terrify all the powers and principalities of this world, right?) Perhaps, but it also underscores that Jesus, even before the Second Coming, is a very present Lord: the unseen guest at every meal.

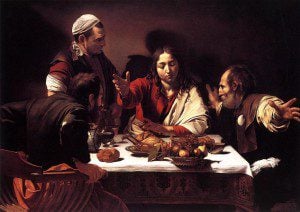

So this prayer also centers hospitality as a Christian virtue, bringing to mind the Emmaus meal where Cleopas and his friend welcome the resurrected Jesus to their table and finally recognize him at the breaking of bread. As much as I associate “Come, Lord Jesus” with the familiar intimacy of family, it’s also the one prayer I’ve shared most often (outside of worship) with strangers — making it a helpful reminder of Matthew 25:35 (“…for I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me…”).

(I should add, however… Last week Leah Libresco of FiveThirtyEight.com shared the results of a survey she conducted on public displays of faith. A convert from atheism to Catholicism herself, Libresco reported that “Nearly half of atheists and agnostics in the survey feel extremely or very uncomfortable when they eat with someone who says grace before meals.”)

“And let these gifts to us be blessed, Amen”: Two years after his initial post questioning the prayer, Veith came back with a theological defense of it. “Above all,” he concluded, “it is a prayer that focuses upon Christ’s presence–asking Him to come into our lives, into our vocations, into our family as everyone is seated around the table–and acknowledges Christ’s gifts, that the food we are about to eat comes from His hand and that ordinary life is the sphere of His blessings.” It is a table grace, after all, because it reminds us that we depend on God’s mercy in all realms of life. And the blessing of God is not necessarily the material wealth associated with another popular prayer, but the simple, sustaining mercies of food, drink, shelter, and the loving presence of other people.

(At the same time, G.K. Chesterton was no doubt right to say grace not just before meals, but “before the concert and the opera, and grace before the play and pantomime, and grace before I open a book, and grace before sketching, painting, swimming, fencing, boxing, walking, playing, dancing and grace before I dip the pen in the ink.”)

The other mealtime prayer used on my mom’s side of the family (also Moravian in origin) reiterates similar themes, but adds the crucial message that, being so blessed, we are to bless others. It’s a shame you can’t hear us sing it in full four-part harmony, but the words are still powerful:

Be present at our table, Lord

Be here and everywhere adored

These mercies bless and grant that we

May strengthened for thy service be

Amen.