At one point in the first debate between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, Trump was asked what he meant by a remark that Clinton did not have a presidential “look”. To be sure, it already is common knowledge that women’s looks are of interest to this candidate. Furthermore, nearly all elements of the possibility of a female president feel exhausted, overanalyzed, by now. Still, though Trump claimed to doubt Clinton’s “stamina” instead, concern over her “look”–face, hair, clothing, all the physical trappings of femaleness–deserves a moment of reflection.

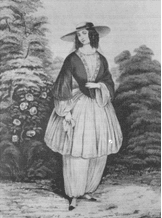

What women wore was relevant to debates in nineteenth-century America too. Mid-nineteenth century American Protestant women took up many causes attacking social ills or promoting social betterment. Women engaged actively in signing petitions, writing articles, holding meetings, joining demonstrations, addressing assemblies. Alongside female-fueled campaigns for temperance, anti-slavery, and access to voting came dress reform. The right to wear pants was claimed on behalf of mobility, health, moral improvement. For women, dress reform meant refusing the corset and wide, heavy skirts, that feminine get-up that mangled ribs and internal organs, dragged hemlines in the dirt, and made doorways hard to pass, all that fabric in service of exaggerating the female distinctives of waist and hip. In place of conventional middle-class dress some American women adopted a tunic-and-trousers combo, a top extending about knee length with loose blousy pants: “bloomers.” The costume got its name from its adoption by Amelia Bloomer, a dress-reform champion and editor of the temperance newspaper, The Lily. Some men and women counted the costume immoral. To us it may appear exceedingly modest, even frumpy. Detractors faulted it for showing too much, though it hardly reveals anything except the fact that women’s lower parts split into two legs, which presumably all already knew. The bloomer outfit is more modest, arguably, than the wasp-waist-big-hips plumage women were supposed to wear. Indeed, it was practically a pantsuit.

That bloomer costume made sense to some in the women’s rights movement. Women’s “look” became political in part because women seeking rights of citizenship experimented with outfits that seemed unwomanly. Lucy Stone, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony took up wearing bloomers. But it caused them so much trouble that some consigned their bloomers to the closet. When wearing that outfit generated opposition that detracted from efforts to secure voting rights, Elizabeth Cady Stanton chose not to wear it. She went back to giving speeches in conventional womanly garb. When getting attention for what she wore meant distracting attention from what she wanted to say, she changed what she wore.

In some ways American mores, along with American politics, have come around: we judge pantsuits problematic now because they seem too modest. We should be long past a point where a candidate’s pantsuit or shoes deserve any comment at all within political discourse. Clinton’s look, anyway, long ago accommodated public tastes about the “look” appropriate for political women. The way a woman is “marked,” in Deborah Tannen’s phrase, no longer ought to occupy our attention, visual or otherwise, in the evaluation of candidates. This is no brief for Hillary Clinton, or that campaign’s unsuitable policies, but insistence that we learn to to stop worrying about a female candidate’s “look,” and look away or look dismayed when an opponent calls attention to it rather than her politics.