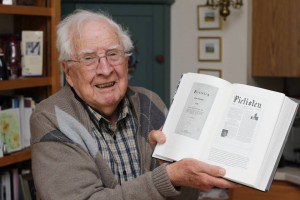

Glen Wiberg died last Thursday, just a few weeks shy of his 92nd birthday.

If you don’t have any connection to the Evangelical Covenant Church, you likely have no idea what I’m talking about. This might be the last sentence in the post that you think you need to read.

But if you’re part of the Covenant, that sentence announced an epochal event: the passing of a powerful preacher, beloved pastor, thoughtful hymnodist, and influential writer and editor who shaped worship and education in our small denomination for decades. Moreover, Glen embodied the Pietist ethos that many of us see as being a Covenant distinctive. Yale Divinity School has more famous graduates, but Glen’s death is at least as big a headline for many Covenanters as the failure of the GOP health care plan in Congress, the terrorist attack in London, or anything else of national or international import.

Considering the gap between those two responses reminds me of something I noticed when my colleague G.W. Carlson retired in 2012. Having been a larger-than-life part of the Bethel University community for nearly half a century, GW earned what I called

an odd kind of celebrity: to be so well known to thousands of people that your mere initials conjure instant recognition and appreciation, while being so little known beyond that community… that it would take me considerable time to even begin to describe him to anyone else.

When he died suddenly last February, GW’s tenure on the St. Paul (MN) School Board earned him a half-page obituary in the Star Tribune, in which the writer quoted my assessment of GW’s memorial service at Bethel: “…as close as the Baptists would get to a state funeral.” For the hundreds who showed up, that’s what it felt like: the celebration of the transformative impact of one life on many others. But for hundreds of millions more, that event was overshadowed by a million other things that happened on February 28, 2016.

* * * * *

Writing tributes to and building digital projects about people like Glen and GW has to compete for my scholarly attention and energy with topics as grandiose as world wars and “hope for the renewal of Christianity.” But I increasingly feel like it’s time well spent.

First, doing that kind of historical work reminds me that I’m not just a historian in the abstract — I’m a historian who participates in particular communities, a member of bodies within the larger Body of Christ. And my professional knowledge and skills can occasionally serve those communities. “My own personal remembering of fallen friends served as a catalyst for collective remembering,” I realized in the wake of GW’s death. “But even if we’re not writing or speaking about friends for friends, I think there’s a degree to which the work of history is meant to build communities — to help people who share a common present and future look back at their common past.”

Second, while I do believe that history helps us ask better questions and seek better answers, we sometimes forget that learning to think critically is about more than being critical. Occasionally taking up small projects like a tribute to “an odd kind of celebrity” is a good way to keep historians from becoming like the critics, who, in the words of novelist Irwin Shaw, are “made by their dislikes, not by their enthusiasms.” In short, to think critically is also to appreciate, “to grasp the nature, worth, quality, or significance of” someone or something that might otherwise be overlooked.

Or, Webster’s suggests, to appreciate is “to recognize with gratitude.”

And whenever Christians do something out of gratitude, they are actually responding to grace: an undeserved gift of God, often given in such a way as to escape the notice of the world.

And that sounds to my ears like Glen and GW.

I know it’s starting to sound like I’m going back on my oft-expressed wariness about hagiography. But one of my retired colleagues from Bethel, a literature scholar who knows his way around the English language, suggested last month that I rethink the meaning of that word:

“Hagiography” we usually think of as “saints’ lives,” or (more cynically) an attempt to beatify someone whose life doesn’t deserve it. But we could also think of it as “writing about the holy,” not just the “holy ones.”

Glen and GW were both Protestant enough that they wouldn’t want beatification. But I think they’d be okay with the idea that a historian reflecting on their lives is, in a small way, “writing about the holy.”