Between my own blog, this one, and a couple others, I’ve written about 1,500 posts in the last six years. I try to do it well, with a less formal tone and much greater pace than typical academic writing but still reflecting a reasonably careful degree of prior research. But I’m afraid that my haste sometimes leads me to sloppiness — worse yet, sloppiness on topics where I’m writing outside of my fields of direct expertise and already at risk of stepping heedlessly into scholarly minefields.

As in the case of something I wrote over the weekend…

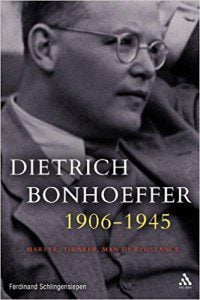

On Saturday I encouraged readers to seek out Come Before Winter, a new movie about the last days of the German pastor, theologian, and martyr Dietrich Bonhoeffer. I mentioned that it featured clips of an interview with Ferdinand Schlingensiepen, a German scholar whose 2006 biography of Bonhoeffer was published in English in 2010. At least among American readers, I noted, that work “was overshadowed by those written by Charles Marsh and Eric Metaxas….”

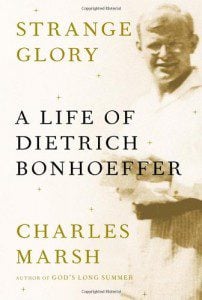

But then I went on (unnecessarily, I fear) to point out that Schlingensiepen has criticized both Metaxas and Marsh “for wrenching the German martyr out of his historical and theological context.” I quoted the following passage from Schlingensiepen’s dual review of Marsh’s Strange Glory and Metaxas’ Bonhoeffer:

Marsh and Metaxas have dragged Bonhoeffer into cultural and political disputes that belong in a U.S. context. The issues did not present themselves in the same way in Germany in Bonhoeffer’s time, and the way they are debated in Germany today differs greatly from that in the States. Metaxas has focused on the fight between right and left in the United States and has made Bonhoeffer into a likeable arch-conservative without theological insights and convictions of his own; Marsh concentrates on the conflict between the Conservatives and the gay rights’ movement. Both approaches are equally misguided and are used to make Bonhoeffer interesting and relevant to American society. Bonhoeffer does not need this and it certainly distorts the facts.

In retrospect, I think I did wrong to include this quotation — or, at least, to include it without adding any kind of critical comment. Here’s why:

1. Start with the fact that I was unable to read Schlingensiepen’s review of Metaxas and March in its entirety. I found the quotation in question embedded in a review of his Bonhoeffer biography by historian Kyle Jantzen. Unfortunately, the link back to Schlingensiepen’s actual review was broken. I don’t have any reason to think that Kyle took it out of context, but I should have made more clear that I was reading the quotation indirectly.

2. While I have read Metaxas’ biography and can easily how see Schlingensiepen came to the conclusion he did, I have not read Strange Glory.

Those points alone probably should have led me to rethink my decision to include so negative an assessment as Schlingensiepen’s, especially when it did nothing to advance my central point in the post: that readers who are already interested in Bonhoeffer should look into Come Before Winter. But since I did publish the post with that quotation, let me take the mea culpa further…

3. On the basis of several rave reviews of Strange Glory (and its winning the 2015 Christianity Today book award for history/biography, just ahead of Philip’s WWI book), I don’t think I should have left unchallenged Schlingensiepen’s claim that Metaxas’ and Marsh’s approaches are “equally misguided.”

3. On the basis of several rave reviews of Strange Glory (and its winning the 2015 Christianity Today book award for history/biography, just ahead of Philip’s WWI book), I don’t think I should have left unchallenged Schlingensiepen’s claim that Metaxas’ and Marsh’s approaches are “equally misguided.”

Nor that Marsh “concentrates on the conflict between the Conservatives and the gay rights’ movement.”

From initial reviews of Strange Glory, I knew enough to know that Marsh did explore Bonhoeffer’s sexuality, specifically the nature of his relationship with an earlier biographer, Eberhard Bethge. (Here you might read Wesley Hill’s insightful review for the late, lamented Books & Culture.) On this point, at least, a Bonhoeffer scholar as significant as Victoria Barnett, a historian at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum who edits the English-language version of Bonhoeffer’s works, did take issue with Marsh’s translation and interpretation.

But she offered that critique as an addendum (also linked in Kyle’s article) to an earlier review essay that called Strange Glory “an eloquent, well-written portrayal of Bonhoeffer and his theological development from his young student days to the end of his life”; overall, she found it a significant new biography that offered meaningful re-interpretations independent of the passages about sexuality (which seem to make up only a small fraction of the book).

Indeed, I should have dug enough to read at least one or two more of the many reviews that, whatever they thought of the passages on sexuality, still gave high marks to Strange Glory. I’m especially embarrassed that I didn’t think to look back in our own archives here at The Anxious Bench, where I’d have turned up John’s response to Strange Glory, elaborating on a glowing review in The Christian Century in which he had praised Marsh for writing “a moving, melancholy portrait” of Bonhoeffer.

Had I still decided to leave in Schlingensiepen’s critique of Marsh, I could have at least tempered it with this passage from John’s post, which would have reinforced my actual purpose for writing the larger post:

Ultimately… arguments over Bonhoeffer’s sexuality distract from the true meat of Strange Glory: Bonhoeffer’s fierce commitment to the church of Jesus Christ and his relentless attempt to answer and re-answer the fundamental questions that Christians of each generation face.

So let me close with some apologies:

First, to Charles Marsh, who has now picked up a chastened reader — at the potential cost of a slight dent in his formidable reputation as a thoughtful historian who does far better than me in taking up the “scholarly vocation to the church” that I keep claiming for myself.

Second, to the makers of Come Before Winter, whose movie doesn’t touch on these debates and deserves to be seen on its own merits.

And I do appreciate Schlingensiepen’s contributions to that film — as I wrote in the initial post, that the movie gives Americans the chance to hear from European scholars is one of its principal benefits. So third, let me apologize to him: even if I’m not quoting his critique out of context, I surely don’t want readers to judge his ample scholarship on Dietrich Bonhoeffer on the basis of a single quotation contained in my blog post! (Here again is how you can buy his Bonhoeffer biography. Read it and the others and judge for yourself — I will.)

And I do appreciate Schlingensiepen’s contributions to that film — as I wrote in the initial post, that the movie gives Americans the chance to hear from European scholars is one of its principal benefits. So third, let me apologize to him: even if I’m not quoting his critique out of context, I surely don’t want readers to judge his ample scholarship on Dietrich Bonhoeffer on the basis of a single quotation contained in my blog post! (Here again is how you can buy his Bonhoeffer biography. Read it and the others and judge for yourself — I will.)

Fourth, to my colleagues at The Anxious Bench, who are invariably more cautious than me when blogging. Hopefully this post gets John’s 2014 review some renewed attention.

Finally, to Kyle Jantzen, whose article in Contemporary Church History Quarterly raises important historiographical questions and doesn’t rise or fall on the aforementioned quotation from Schlingensiepen.

Indeed, knowing that I’ve now said more than enough about Dietrich Bonhoeffer, I’ll close this mea culpa with Kyle’s own, rather apropos concluding paragraph. His last sentence alone is worth more than all those that I’ve written today and Saturday.

What must be clear… is that Bonhoeffer is exceedingly complex. No biographer will portray him faithfully without a great deal of historical and theological spade work. Schlingensiepen focuses on Bonhoeffer’s intellectual curiosity, strong moral compass, courage, and creative modern theology. I have suggested that these characteristics make Bonhoeffer unpredictable, paradoxical, and impossible to pigeonhole. Conservatives value a Bonhoeffer who teaches the Bible, stands upon confessions of faith, and takes the lordship of Christ so seriously that he is willing to kill or die for it. He is, to be sure, a serious Christian. Liberals value a Bonhoeffer committed to peace, internationalism, and ecumenical Christianity—a cultured and curious man open to literature, music, and modern life, including an intellectually critical relationship with both the Bible and confessional theology. In Schlingensiepen’s biography of Bonhoeffer, we discover a man who encompasses both of these images and somehow holds them together in a life marked by a most radical, subjective, and challenging form of Christian discipleship. Here is someone worth knowing.