This month my wife and I have been enjoying new episodes of Outlander, the first in that series since last July. So it seemed like a good time to dip into my archives and update my argument for that cable TV drama and FX’s The Americans as exemplifying the four criteria by which this historian assesses historical films:

- Are they entertaining? (understanding that there are multiple meanings to the verb “entertain”)

- Are they truthful? (but in terms of “verisimilitude” more than “accuracy”)

- Are the makers genuinely interested in the past on its own terms? (or, for example, are they just using it as a dimension of the set)

- Do they inspire further historical study, or even historical thinking? (e.g., do they help us think about historical context and complexity, change over time and continuity, etc.)

In case you’re not familiar with The Americans or Outlander, let me summarize characters and plots that are, by their nature, overly confusing:

- Based on the books by Diana Gabaldon, Outlander stars Irish actress Caitriona Balfe as Claire Randall, a British army nurse visiting Scotland with her historian husband Frank just after World War II. Through a mechanism best not thought about too much, she travels back in time to the Scottish Highlands in the 1740s, on the eve of the Jacobite revolt that culminated in the disastrous battle of Culloden. Saved from a sadistic English officer named Black Jack Randall (who — coincidences! — is one of Frank’s ancestors), Claire marries and then falls in love with a Highlander named Jamie Fraser (Sam Heughan). While mostly set in the 18th century, the story occasionally moves back into the 20th, where Frank searches for — and eventually finds — his disappeared wife.

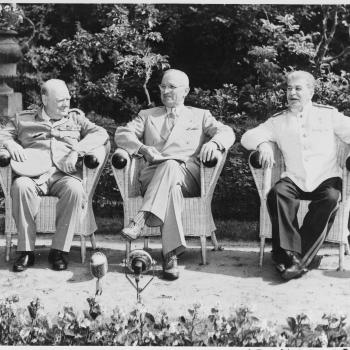

- The Americans tells the story of Philip (Matthew Rhys) and Elizabeth Jennings (Keri Russell), two Soviet spies in the early 1980s, when détente dissolved into the renewed Cold War tensions of the Reagan presidency. Deployed as “sleeper agents” who blend in perfectly with their suburban American surroundings, Elizabeth and Philip work undercover at great risk to themselves (an FBI agent — coincidences! — moves in next door in the pilot episode) and the many people they kill. It’s also a story about a marriage that was arranged by the KGB but generates real, complicated feelings, and the Jennings’ two children, Paige and Henry, play increasingly important roles as well.

(Speaking of the “many people [the Jennings] kill”… Before going any further, let me emphasize that both series live up to their TV-MA ratings. They’re quite violent, include some profanity, and often feature sexual content and (especially Outlander) nudity. I think they’re still excellent shows that exemplify most of my criteria, but they’re not everyone’s cup of tea. And the two episodes that concluded the first season of Outlander featured such graphic depictions of torture and rape that even I found myself fast-forwarding regularly.)

I’ll try my best to avoid spoilers, at least from the most recent season of each. That’ll be easy for The Americans, since my wife and I watch it on Amazon Prime, which isn’t yet streaming season 5; harder for Outlander, whose third season just started.

Okay, enough table-setting. So why do I think Outlander and The Americans are the best historical dramas on TV — and better than most historical films?

They’re entertaining

First things first: both series are well-made, dramatically compelling diversions. The Americans has received fourteen Emmy nominations and routinely makes critics’ year-end top ten lists. Outlander continues to be snubbed by TV’s leading award show, but has received generally glowing reviews. (It’s currently at 96% “fresh” ratings on the Rotten Tomatoes critical aggregator, a point ahead of The Americans.) I’m particularly impressed by the acting of the two Americans and by Outlander‘s Balfe and Tobias Menzies (given the dual role of Frank and Black Jack Randall).

The latter series feels like it can’t always escape the weaknesses of its source material, but its showrunner, Ronald D. Moore, is one of my favorite TV writers thanks to his work on Battlestar Galactica and several iterations of Star Trek. That might make it sound like Outlander is a science fiction show, but Moore tends to minimize those elements and play it as a historical drama — set in the same place, but in two eras different from each other and our own time. It, like The Americans, succeeds according to my second definition of “entertaining”: inviting us into different pasts, and immersing us as something more than a tourist just passing through.

They’re truthful

I’m not concerned so much about how these series interpret the past “as it actually happened.” (TV series can do a bit better here, since storytellers given multiple episodes and seasons aren’t as tempted to condense timelines and casts of characters as those allowed only two hours of screen time.) More so, I want historical films and TV shows to help us understand what it felt like to live in these places and cultures at these times, which requires historical verisimilitude.

No doubt, this is why I prefer historical fiction to docudramas. Presenting a film as being “based on a true story” inherently blurs the line between history and fiction. So even when it’s based on considerable research and made with skill and vision, such a movie is going to ring false to historians with heightened expectations of historical accuracy. While Outlander and The Americans develop their stories within the outlines of actual historical events (and include actual historical figures — and, in the latter case, actual footage from news and other media of the time), they are not trying to tell “true stories,” just truthful ones.

And by the standards of what I’ve called verisimilitude, both shows do very well. I’m not enough of a historian of the 18th century or Scotland to vouch for everything about Outlander. (Was King James so beloved among Scottish Catholics that they quoted his version of the English Bible instead of the Douay-Rheims?) But I’m especially struck by the attention to what people wear. (Moore happens to be married to the show’s chief costume designer, Terry Dresbach.) In a cast discussion in New York, Heughan mentioned learning about the relatively muted color palate of the 18th century characters, which is appropriate — the notion of bright red tartans is a 19th century invention (of Sir Walter Scott or later Victorians, I’m not sure). Moore explained that he added a scene to an early episode in which Claire puts on her new clothes for the first time, precisely because “it was part of her transformation from a 20th century woman to an 18th century woman.”

The Americans may seem less impressive on this count, since it’s set in suburban Virginia, only three decades ago. But it takes some genuine skill to evoke the subtle foreignness of the early Eighties without letting the show become an exercise in nostalgia. Clothing, hairstyles, cars, computers, music, EST seminars… And the show’s occasional flashbacks to Philip and Elizabeth’s earlier lives in the Soviet Union require the creation of an even more alien past. The show’s regular use of Russian helps disorient us here, just as Gaelic helps makes Outlander‘s viewers, like its heroine, feel like Sassenachs (that is, “outlanders”).

They’re interested in the past on its own terms

Here let me finally bring myself around to the focus of this blog and talk about religion. It takes little effort for American filmmakers to show utter disinterest in the faith and devotion of earlier ages, but its treatment of belief (and unbelief) is one of the strengths of The Americans.

Starting in season 2, the Jennings’ teenage daughter, Paige, undergoes a Christian awakening through the mentorship of a pastor-activist who could have jumped out of the pages of David’s excellent history of politically progressive evangelicalism. Such a plot device isn’t unusual, but it rarely survives one story arc. (Cf. Lyla’s quickly forgotten conversion in my favorite TV drama of all time, Friday Night Lights.) Instead, The Americans’ writers have taken Paige’s new commitments seriously and made them more, not less, important to the narrative in succeeding seasons.

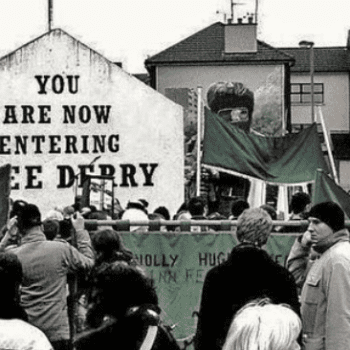

Most notably, Paige’s conversion prompts Elizabeth and Philip to articulate their own lack of belief, which makes The Americans the rare TV show that takes atheism seriously. This theme was first hinted at in the show’s second episode, when the Jennings have to coerce a devout African American woman into planting a bug: “People who believe in God always make the worst targets,” complains Philip. But Paige’s defiant embrace of Christianity fans the flames of her parents’ hostility to organized religion. In place of theism, Elizabeth continues to cling to the humanistic idealism of a Soviet generation inspired by the memory of resistance to fascism and the witness of popular revolutions in the Third World. (Elizabeth soon takes a novice spy from Nicaragua under her wing.) Meanwhile, Philip sinks into disillusionment as the Soviet government proves to be at least as corrupt as its adversary. (On the notion of the Soviet Union as an “empire of justice,” simultaneously hopeful and cynical, see Odd Arne Westad’s The Global Cold War.)

Tellingly, Elizabeth assumes that her daughter’s commitment to social justice Christianity makes her a good candidate for recruitment to the Soviet cause, a major story line in season 3. But that season ended on a different note. The KGB allows Elizabeth to fly to Berlin to see her dying mother one last time, and to take her own daughter along — all part of the recruitment effort. But as that storyline resolves, we see Paige praying for her grandmother, while Elizabeth can only watch.

On this count, Outlander is less impressive. Religion is central to several episodes: a neo-druidic ritual on Samhain is what helps send Claire back to the 1740s, where she gets caught up in an exorcism and a witch trial that both feature the same sinister Catholic priest; in season 2, she befriends an apothecary with an apparent interest in the occult and works at a hospital alongside a more sympathetic nun who helps her grieve a terrible loss. But too often, it feels like religion is just another layer of costume; the characters cross themselves against superstition, but anything deeper than that is brushed aside as easily as Frank dismisses a vicar’s housekeeper who lends credence to old tales about time traveling: “I simply do not share your beliefs.”

Most importantly, they prompt historical thinking

But where Outlander succeeds at least as much as The Americans is in its ability to get its audience to think more historically about the past. Whatever its implausibilities, the device of time travel makes it almost impossible for the show to avoid the so-called “five C’s of historical thinking.”

For example, context and change over time. As much as she needs to dress the part of an 18th century Scot, Claire quickly learns that she must disguise her worldview. Just as the Jennings need to understand and blend into a capitalist society whose values they (well, Elizabeth) resolutely oppose, Claire struggles to comprehend — and not contradict — premodern mores about everything from gender roles to criminal justice. In the process, she and we are regularly shaken out of what Robert Darnton famously called “the comfortable assumption that Europeans thought and felt two centuries ago just as we do today—allowing for the wigs and wooden shoes.” Or, in this case, the kilts and corsets.

Occasionally, she loses her cool. During the show’s wheel-spinning interlude in Paris early in season 2, Claire tires of the Rococo frivolity of her aristocratic acquaintances and finally bursts out:

Doesn’t it distress any of you, how this city treats its poor and underprivileged? Surely you must see the staggering numbers of them as you travel through the city. Just yesterday I saw a woman and her child dead in the middle of the road. It’s absolutely horrible. Surely we must do something to change the situation.

“Je suis tout à fait d’accord,” nods a friend, who then suggests an ancien régime solution: “The gendarmes should remove them to the less desirable parts of the city.”

But to their credit, both shows usually step back from facile moralizing. They savor the complexity of their characters and conflicts, another advantage long-developing TV dramas have over most feature films. Outlander doesn’t make the English side in the Jacobite uprising particularly appealing, but it also reveals the internal contradictions of Scottish nationalism. The Americans learn to both love and hate their country, whether they’re thinking of their homeland or the place they inhabit.

(At their best, these series don’t encourage moral judgment, but what Tracy McKenzie has called moral reflection. In particular, these two frequently violent dramas use their historical settings to help viewers wrestle with the reality of evil, the corrosive consequences of sin, and the potential for redemption.)

But for both The Americans and Outlander, the single most important historical “C” is contingency. Thomas Andrews and Flannery Burke define it as “a powerful corrective to teleology, the fallacy that events pursue a straight-arrow course to a pre-determined outcome, since people in the past had no way of anticipating our present world.”

But in Outlander they do! Claire knows the fate of Bonny Prince Charlie and the clans that took the field at Culloden on April 16, 1746. So she tries to change that outcome, making season 2 an extended meditation on the modern assumption that history is indeterminate, that (Andrews’ and Burke’s words again) “individuals shape the course of human events.” In the end, she learns what historians frequently have to accept: cause and effect aren’t that easy to understand, even with centuries of hindsight.

In The Americans, Philip and Elizabeth don’t know what’s coming in 1989-1991, but they can sense the mounting urgency and deepening weakness of the Soviet government. They continue to carry out their mission, one we know to be futile. But if we find the stories suspenseful, aren’t we being invited to reconsider the inevitability of Western victory in the Cold War? And if we find the characters sympathetic, aren’t we forced to reconsider its meaning as well?