But Jesus said, “Suffer little children, and forbid them not, to come unto me: for of such is the kingdom of heaven.” Matthew 19:14 KJV

I realize I have written several blog posts about books. This betrays my enjoyment of world cinema. I am a firm believer in the power and persuasion of good films, and think they are a valuable tool to discuss faith and history. I have been somewhat fascinated by the Soviet director Andrei Tarkovsky, first because the Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek often references him, but especially since he writes about film as an artistic, spiritual practice. My faith-integration ears perk up when I hear such comments.

My goal was to focus on Tarkovsky’s sense of mysticism and spirituality in his films; this was a contentious idea while making movies in the Soviet era. As his biography points out, Tarkovsky was a complicated man, who lived a frustrated life because he would often struggle to be able to produce his type of films. However, instead of writing about Tarkovsky’s view of art and mysticism, his first film struck a more ethical idea especially in the power of cinema (the following images are from IMBD).

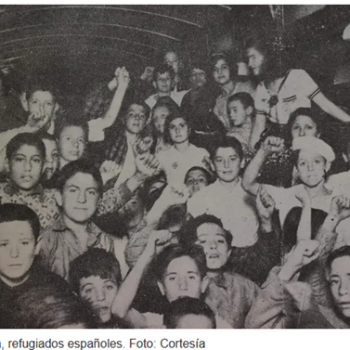

Ivan’s Childhood is considered Tarkovsky’s first major hit that put him on the map of cinema’s great directors. The story opens with an emaciated Ivan stumbling upon a Soviet camp and insisting on passing information that he witnessed. He is brought to a young Lieutenant Galtsev, who takes care of the boy. It is confirmed that Ivan, in fact, is a scout for the Soviet army. What is this child doing here?

Ivan often goes in and out of dreams, but each time the dream is usually interrupted with the death of his mother. He is an orphan, angerly bitter at life because there is nothing but violence all around him. He is shown kindness by some of the Soviet officers, who try to help him escape at the climax of the movie. They desire some type of future for him.

The movie starts to wrap up with the defeat of the Nazis and the Soviets in Berlin, celebrating their victory and accessing the situation. They rummage through the records of POWs, who have been executed—shot, hanged, shot. One of the Soviet soldiers innocently suggests: “Won’t this be the last war on earth?” Unfortunately, the movie concludes with Lieutenant Galtsev discovering paperwork that reveals that Ivan was executed by the Nazis. Prior to this revelation, Tarkovsky shows historical footage of the poisoned children of Joseph Goebbels, Nazi Minister of Propaganda. The film ends with Galtsev imagining Ivan’s execution that suddenly shifts to a happy dream of Ivan on the beach with his mother and a young girl, who had appeared in an earlier vision.

Tarkovsky was unable to truly forget the horrors of WWII that he experienced as a child. He explains his reasons for making the film: “I wanted to convey all my hatred of war. I chose childhood because it is what contrasts most with war” (Interviews, 3). Evidently, the French existentialist philosopher Jean Paul Sartre loved the film enough to defend it in the Italian press. Sartre declares:

“Ivan is mad, that is a monster; that is a little hero; in reality, he is the most innocent and touching victim of the war: this boy, whom one cannot stop loving, has been forged by the violence he has internalized. The Nazis killed him when they killed his mother an massacred the inhabitants of his village. Yet, he lives.”

Sartre noticed this same look in the youth that experienced the Algerian War against France. Tarkovsky film succeeds where our textbooks and other war movies fail us—forcing us to consider the irreparable damage war has upon children. In response to Sartre, who claimed that war produces monsters and devours heroes, Tarkovsky agrees: “There is no winner in a war. When one wins a war, one loses at the same time” (Interviews, 164).

It just happened to be the week I was showing The Mission to my World Civilizations class. I have been showing this film to students for almost 20 years. Just previously watching Ivan’s Childhood helped me focus on something different with this film.

Once the former mercenary and slave trader Rodrigo Mendoza, played by Robert De Niro, converts and becomes a Jesuit priest, he is befriended by a young Guarani boy. The boys is his shadow. In fact, throughout the making of the movie, the boy hung out with De Niro on the set. Mendoza serves as a mentor to this boy and his young friends because he is mostly surrounded by children in the film. The children feel safe with the former mercenary. The boy smiles and laughs with him, showing that Mendoza is accepted by the Guarani. This relationship continues the process of Mendoza’s humanization as much as his Christianization.

The Catholic leadership decides to abandon the missions throughout the Amazon area of South America, leaving the inhabitants exposed to Spanish forces that want to hand the area off to the Portuguese. Mendoza and some of the other Jesuits remain at the mission. The young boy moves the story along by finding Mendoza’s old weapons and asking him to lead the Guarani resistance. Mendoza takes up the charge, enlisting a few of the other Jesuits in the cause of armed self-defense.

When the battle begins, Mendoza intentionally tells the boy he cannot be part of the fighting. He is to remain behind. This does not stop some of the children to pick up weapons and try to join the battle. However, in most cases, the children hide in the jungle, trembling at the sounds of cannon fire, silently watching their loved ones perish. The director zooms in on a young girl’s eyes as a witness to the carnage. She will be one of the few survivors. One of the other times the camera zooms toward a young girl’s eyes is when the narrating archbishop declares in his commentary that the Guarani probably wished that the Europeans would have never showed up in the New World.

At the tragic finale of the film, Mendoza is killed by the Spanish troops before he can hatch out his surprise counterattack. In fact, what interrupts him is his rescue of a boy who was just shot, dangling from a makeshift bridge. Mendoza is seriously wounded in the process and his weapons are disarmed. Stunned, he is killed by a barrage of gunfire. Mendoza’s young stone-faced friend looks on from a distance.

The only glimmer of hope after watching this nightmare is that the boy and a few of his young friends survive. Thus, Mendoza’s sacrifice means that at least some of the children live, and as the narrator notes closing the film, their memory will be preserved. Commentators often juxtapose Mendoza’s armed self defense with Father Gabriel’s nihilistic pacifism (literally leading the people toward the gunfire). As important as that Christian debate, Mendoza concretely rescues at least a few of the children. Still, we might ask would the surviving Guarani children practice the Christ-likeness they witnessed in the Jesuits or would they all be like Ivan?

Many of my students are shocked at the close of the film because it really does not have our familiar happy ending. Neither does Ivan’s Childhood. When war visits a land there are no real happy endings; instead, relief that the killing is over. I have been shocked by The Mission since I saw it as a child. Tarkovsky’s film awoke a similar despair. Perhaps this despair connects to the tragedy of the conflicts in the world today and the relative ease we have to swipe away the stories and the images of violence from our phones. Perhaps it is due to the discomfort of our inability really to do anything. I am more worried of the disconnect that is happening in our time because of the ever present access to information, and our ability to detach ourselves.

Sartre’s words about the hardened faces of children in wartime is prescient. Biographies often reveal that a child who experiences war is forever changed. What kind of future awaits us since we still refuse to learn from history?

As much as I still believe in the power of books to both entertain and to raise consciousness, good movies may have an even greater role since we are so accustomed to video media. Under the guidance of a good director, they will force us to focus on subjects like the horror of war and we might be less prone to look away.