Last time I posted about a largely forgotten satirical novel that I think is a really valuable source for understanding the history of American radical thought – anti-war, anti-racism, anti-militarism. This is Captain Jinks, Hero (1902), by the great American Tolstoyan, Ernest H. Crosby. As I read its portrait of the insanity of war and conquest, I keep harking back to Catch-22. Today, I will get into some more substance about Crosby’s ideas, and I will also emphasize the book’s often magnificent illustrations, by the legendary radical artist of the era, Dan Beard. DO NOTE that you can access the book full text online, for free.

By way of background, Crosby was writing at the time of the fierce national debate over imperialism that followed the US conquest of Spanish territories in the Philippines, Cuba, Puerto Rico and elsewhere. How much of those areas should the US annex for a vast new colonial empire? Crosby was passionately anti-imperialism, and in his novel, he focused his outrage on a popular General of the era, Frederick Funston.

Although the disguise was paper thin, Crosby hoped to avoid libel suits (or worse) by changing the names and places of his story, so Fred Funston became Sam Jinks, and other shifts were quite jokey. West Point became East Point (!), Cuba and the Philippines were merged into the newly conquered colonial territory of the Cubapines, and Jinks/Funston was based in Havana/Manila, “Havilla.” Other names required a bit more thought, so that US forces fight in the ancient empire of Porsslania. Hmm, Porsslan sounds like Porcelain, which is another word for … China. The Fencer rebellion there is obviously intended to be the Boxer movement.

Once you get into the book, the problem is that the material is just so extensive and so quotable. Just for practical purposes, I will here concentrate on one major aspect of the anti-imperial critique, namely the then-common charge of “missionary imperialism.” Crosby believed that missions were multiply wrong, because they assumed that the US was some kind of perfect Christian society, which it evidently was not, and that it had a literally God-given right to impose its views and values on other societies. Worse, the missionaries served as a Trojan Horse for secular imperialism and conquest. When local people attacked missionaries, that provided the US and other Great Powers the excuse to invade and conquer.

Such a resort to secular force made nonsense of Christian values. One smug missionary crows that

“These are great days, Colonel Jinks,” he said. “Great days, indeed, for foreign missions. What would St. John have said on the island of Patmos if he could have cabled for half-a-dozen armies and half-a-dozen fleets, and got them too? He would have made short work of his jailers. As he looks down upon us to-night, how his soul must rejoice! The Master told us to go into all nations, and we are going to go if it takes a million troops to send us and keep us there.

Crosby comprehensively savaged missionaries and their cause, using as example Western misdeeds against the ancient land of Porsslania, or China:

Many years earlier the various churches had sent missionaries to that benighted land to reclaim its inhabitants from barbarism and heathenism. These emissaries were not received with the enthusiastic gratitude which they deserved, and some of the Porsslanese had the impudence to assert that they were a civilized people when their new teachers had been naked savages. They proved their barbarism, however, by indulging in the most unreasonable prejudices against a foreign religion, and when cornered in argument they would say to the missionaries, “How would you like us to convert your people to our religion?” an answer so illogical that it demonstrates either their bad faith or the low development of their intellects.

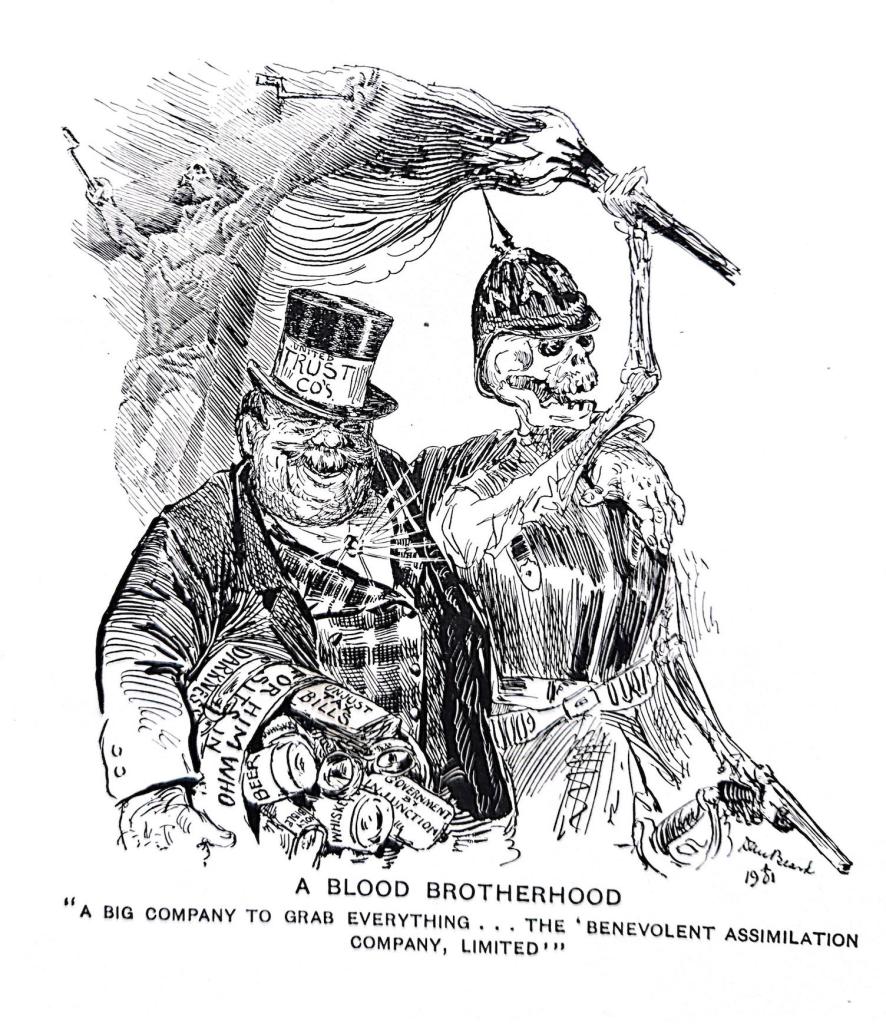

The missionaries of some of the sects, by the help of their governments, gradually obtained a good deal of land and at the same time a certain degree of civil jurisdiction. The foreign governments, wishing to bless the natives with temporal as well as celestial advantages, followed up the missionary pioneers with traders in cheap goods, rum, opium, and fire-arms, and finally endeavored to introduce their own machinery and factory system, which had already at home raised all the laboring classes to affluence, put an end to poverty, and realized the dream of the prophets of old.

Those final words, of course, drip with irony.

The Porsslanese resolutely resisted all these benevolent enterprises and doggedly expressed their preference for their ancient customs. In order to overcome this unreasonable opposition and assure the welfare of the people, the various Powers from time to time seized the great ports of the Empire. … Most frequently the pretext was an attack upon a missionary or even a case of cold-blooded murder, and it became a proverb among the Porsslanese that it takes a province to bury a missionary.

Well, I have heard “It takes a village to raise a child,” but never “It takes a province to bury a missionary.” Gee, is that a book title waiting to happen!

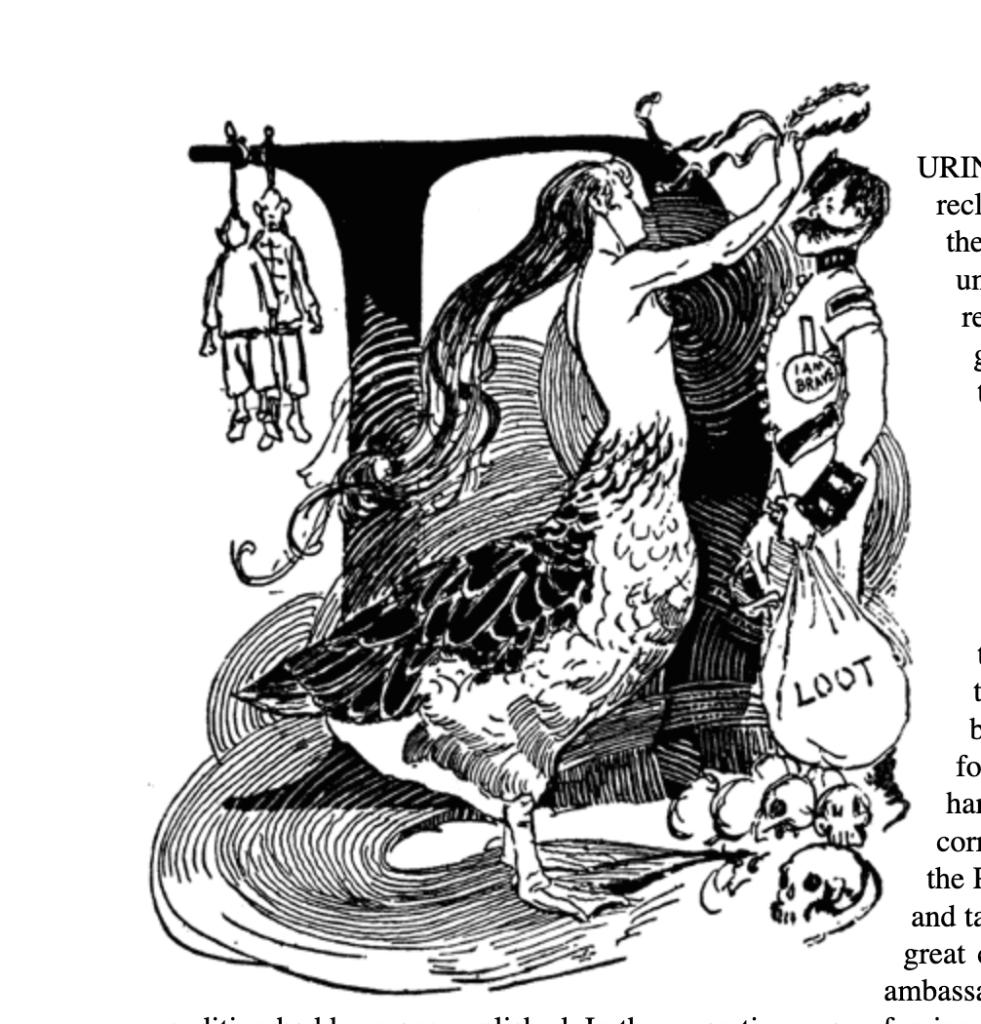

When the US and Allied forces attack China to save their nationals from the Boxer rebels, they undertake mass killings, and they ruthlessly steal everything of value they can find. In the word recently introduced to the English language by the arch-imperial poet Rudyard Kipling, they “loot.” (The word is borrowed from Urdu).

Crosby, obviously, loathed Kipling, and he wrote some viciously accurate parodies of his poems.

America’s Lynching Culture

Crosby spent a great deal of time denouncing the manifold injustices of American society, prominent among which were the crimes of racism, segregation and lynching. If lynching was not horrific enough, this was the time at which mobs took it upon themselves to make the victims suffer even more, by inflicting torture and mutilation, or burning them alive. And these atrocities were widely circulated through photographs and picture postcards

In light of all that, here is Sam setting off to undertake his great imperial venture in the Cubapines, here he will bring the glories of American civilization:

“Even if I don’t do anything very wonderful,” said Sam, “and I hope I shall, I shall be taking part in a great work, and doing my share of civilizing and Christianizing a barbarous country. They have no conception of our civilized and refined manners, of the sway of law and order, of all our civilized customs, the result of centuries of improvement and effort.”

Cleary picked up a newspaper to read.

“What’s that other newspaper lying there?” asked Sam.

“That’s The Evening Star; do you want it?” and he handed it to him.

“Good Lord! what’s that frightful picture?” said Cleary, as Sam opened the paper. “Oh, I see; it’s that lynching yesterday. Why, it’s from a snap-shot; that’s what I call enterprise! There’s the darkey tied to the stake, and the flames are just up to his waist. My! how he squirms. It’s fearful, isn’t it? And look at the crowd! There are small boys bringing wood, and women and girls looking on, and, upon my word, a baby in arms, too! I know that square very well. I’ve often been there. That’s the First Presbyterian Church there behind the stake. Rather a handsome building,” and Cleary turned back to his own paper, while Sam settled down in his corner to read how the leading citizens gathered bones and charred flesh as mementoes and took them home to their children. No one could have guessed what he was reading from his expression, for his face spoke of nothing but a guileless conscience and a contented heart.

So much for “our civilized customs.”

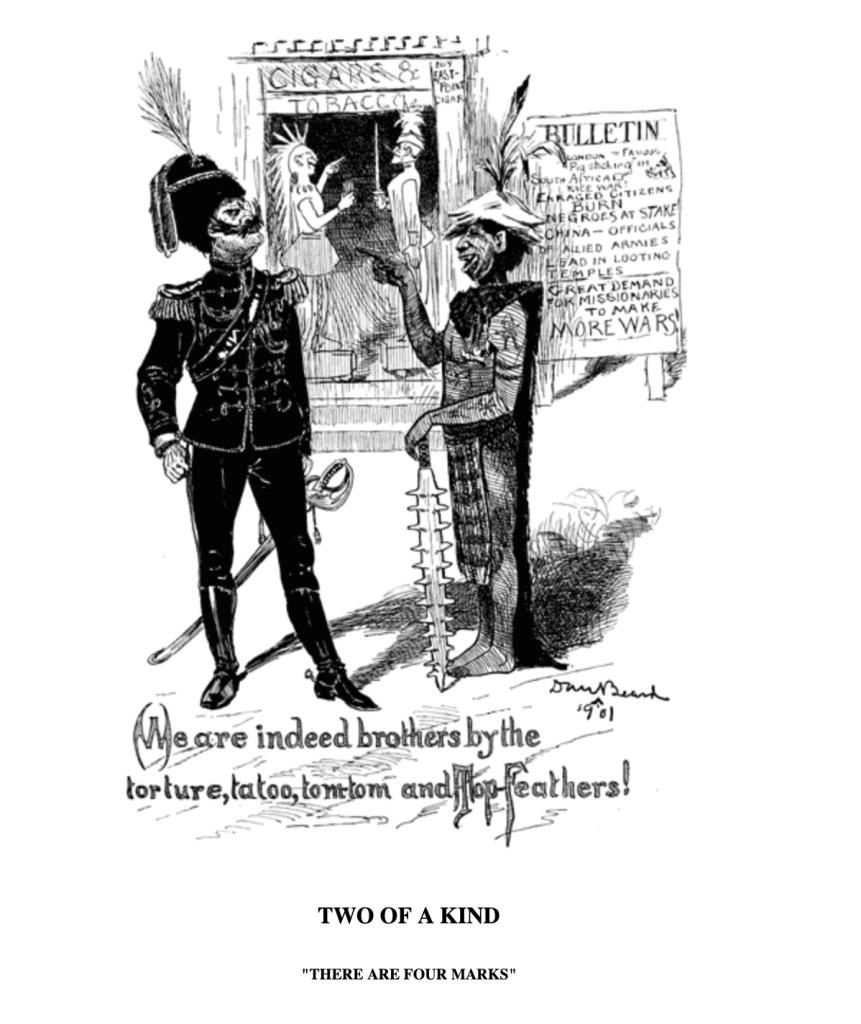

Who Are the Savages?

In a related episode, Sam and Cleary are captured by the much-feared cannibals, the Moritos. They have great difficulty convincing the savages of the realities of American society: why on earth would anyone need prisons or lunatic asylums? As the debate continues, the Americans convince the Morito leader that their own experiences in the US military, and particularly at West Point, mean that they have passed through ordeals and barbaric rituals quite as extreme as anything the cannibals know, so they must in fact be Moritos themselves! The chief is delighted:

“Oh, my brothers!” he cried. “To think that I should not have known you! You torture each other just as we do. You are tattooed just as we are! You have bigger feathers and bigger dances and bigger tom-toms. You are bigger savages than we are! Come, let us feast together.”

Look carefully at the illustration here, and especially the headlines on the board outside the shop:

Look carefully at the illustration here, and especially the headlines on the board outside the shop:

Race War: Enraged citizens burn Negroes at stake.

China: Officials of Allied armies lead in looting temples.

Great demand for missionaries to make more wars!

And so much for Christian civilization.

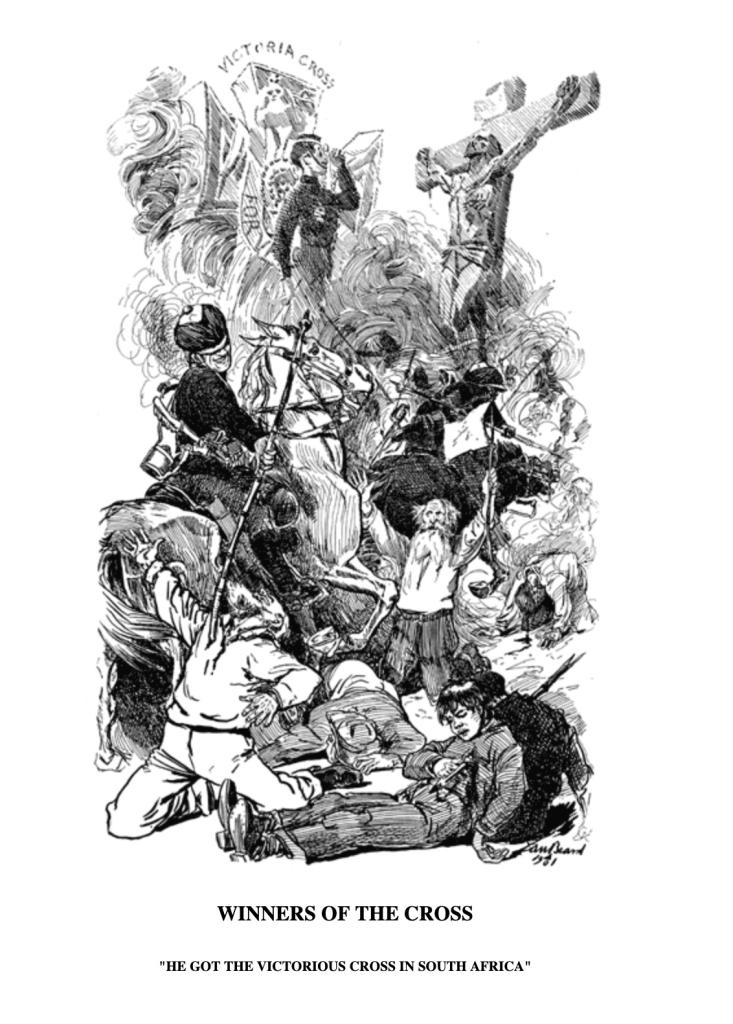

Dan Beard often used Christian religious symbolism to heighten the stark contrast between the notional ideals of American society and the horrific imperial realities – the crosses of war medallions versus the Cross of Christ. (This was also the time of the British war against the Boers in South Africa).

As I say, if you are teaching about American empire, or about American radical history, this really is the gift that keeps on giving.

More next time.