She was of medium height, with intensely black hair drawn back in a knot,

and a head firmly set on her shoulders. When, with her sleeves rolled up,

she was washing clothes, one could see what beautifully turned arms she had.

Her waist revealed the fact that she had borne children.

Her legs were the two pillars of the household.

–The Cypresses Believe in God, José María Gironella, 1953

The theme of my Senior Seminar at the St. Ignatius Institute at the University of San Francisco was warfare. Of all the books we read (most of which I cannot now recall 25 years later), one of them affected me profoundly: José María Gironella’s The Cypresses Believe in God: Spain on the Eve of Civil War. Until I read this book, I did not realize that families like my family could and did appear in literature.

An avid writer since I had first learned to write, I had always made my characters “American” (today I’d say estadounidense/Unitedstatesian), because I thought it was the unspoken rule; I changed my family’s surname to Smith and made us eat dinner the way I saw the Cleavers do on reruns of “Leave it to Beaver.” But reading The Cypresses Believe in God, oh! It was like holding up a mirror to my family. The mother, Carmen Elgazu, was my mother! One of the sons had the same name as my brother. The family observed Lent the way that we observed Lent. This book prompted me to change the books that I read and the stories that I wrote.

Just this week I stumbled upon a story related to The Cypresses Believe in God, that is, I discovered that in 1937, Mexico welcomed 456 children ages 4-12 seeking asylum from the Spanish Civil War. Hence, this post is not about representation in literature (which would certainly be interesting fodder for another day!), but rather, it’s about the fact that despite reading about and teaching Mexico’s history for over 20 years, I am still surprised by what I learn about its past. [I wrote a similar post of discovery two years ago: The court martial of Irish Catholics in Mexico: Los San Patricios and the largest public execution in U.S. military history.]

Given that this post was scheduled to appear on Valentine’s Day, I had been searching for an inspiring story about love in Mexico’s past, something unexpected. I seemed to have found it in Los Niños de Morelia / The Children of Morelia, who were welcomed to Mexico personally by President Lázaro Cárdenas del Río at the port of Veracruz before they boarded a train to Mexico City with the ultimate destination of Morelia, the capital of the state of Michoacán.

It’s not surprising that I had not heard of these children, despite having visited Morelia, because scholarly interest in these refugees is recent. Indeed, a statue commemorating their arrival appeared in Morelia only in 2017.

Los niños españoles / The Spanish children

A sculpture erected in 2017 in front of the Cathedral in Morelia, Michoacán, México

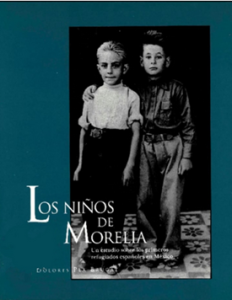

The first significant study I encountered (in my albeit brief online search) is a 1985 publication from the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. A bureau of the Mexican government, the National Institute for Anthropology and History, “investigates, preserves and disseminates the archaeological, anthropological, historical and paleontological heritage of the nation in order to strengthen the identity and memory of the society that holds it” (INAH – Who are we?).

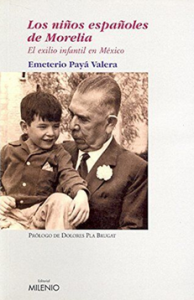

Dolores Pla Brugat’s Los niños de Morelia: Un estudio sobre los primeros refugiados españoles en México (INAH, 1985)

Dolores Pla Brugat, author of Los niños de Morelia: Un estudio sobre los primeros refugiados españoles en México [The Children of Morelia: A Study of the First Spanish Refugees in Mexico, INAH, 1985], explains that prior studies of refugees from the Spanish Civil War barely mention the children. Instead, scholars focus on the minority, the intellectuals, exploring how their presence bolstered the intellectual landscape of Mexico. She explains that for the Mexican State, highlighting the intellectual exiles validated their claim that the refugees’ presence enriched Mexico. She says that the refugees themselves maintained the image that they were primarily intellectuals to avoid being conflated with the Castilians who had colonized Mexico, and in that way ensure Mexico’s receptivity to their presence. With so little known, Brugat’s study endeavored to uncover the hidden history of the non-intellectual refugees, namely, the 456 children. Multiple studies have since appeared, including master’s theses, dissertations, and interviews with some of the exiled children, such as Francisco González Aramburu, ex-niño de Morelia (2004).

What we know is that on May 27, 1937, parents supporting the Republic put their children in the care of a few of their teachers aboard the steamship Mexique, which was bound for the Mexican port of Veracruz, anticipating a separation of only a few weeks. But the civil war raged on. After Francisco Franco’s Nationalist forces succeeded in gaining full victory on April 1, 1939 – followed swiftly by the outbreak of World War II – retrieving or returning the children was not possible.

“Lázaro Cárdenas del Río, ex-President of Mexico, with the Children of Morelia”

According to a recent newspaper article from Morelia, President Lázaro Cárdenas del Río spent time with these children (see photo above), who were enrolled in various schools, including la escuela industrial España-México in Morelia, with a separate site for girls and boys. The children lived for close to ten years in homes that Mexico provided, after which some remained in Morelia and others left the country. Until recently, the Children of Morelia gathered in reunions, with the youngest of them close to 90 years old. (See Los Niños de Morelia, la historia de los refugiados españoles, El Sol de Morelia, April 24, 2024 for information and images).

La escuela industrial España-México in Morelia

So, do all the sources support the idea that acceptance of these young refugees was an example of love on the part of Mexico? The same year as Dolores Pla Brugat’s Los niños de Morelia: Un estudio sobre los primeros refugiados españoles en México appeared, one of the Niños de Morelia, Emeterio Payá Valera, published a biography: Los niños españoles de Morelia: El exilio infantil en México (1985). The book has since been revised, expanded, and reissued several times, most recently in 2002. His work demonstrates that rather than serve as a simple story of solidarity, Mexico’s acceptance of refugees from the Spanish civil war had its shadows.

This point is further evidenced by Daniela Lechuga Herrero’s 2017 senior thesis at UNAM (National Autonomous University of Mexico), “Memorias de un cuerpo roto. Las y los Niños de Morelia, 1937-1948,” which recreates the experience of exile from information gleaned from archival documents, secondary sources, and from interviewing six Children of Morelia. Lechuga Herrero describes how these children passed from one institution to another, forging connections with one another as fellow refugees while simultaneously forming their individual identities. What she sees is evidence of the agency of children in the context of exile.

She also sees mistreatment.

Whereas the school buildings served their purpose initially, they soon fell into disrepair, overseen by a rotating line of directors, some of whom were despotic. By 1939, numerous children had fled, a few had disappeared, others were entrusted to local families, the Spanish Consul, or their own families who had come over, and one female student had married. Lechuga Herrero describes how locals would jeer at the Spanish refugee children, locking up their stores when school let out to avoid being robbed. Her descriptions challenge the narrative of Lázaro Cárdenas del Río’s – and indeed all of Mexico’s – amicable embrace of these Children of Morelia. Her work underscores the experience recounted by Emeterio Payá Valera in his 1985 biography.

Perhaps this was not a love story appropriate for Valentine’s Day after all.

For a list of 446 of the 456 Children of Morelia, see here.