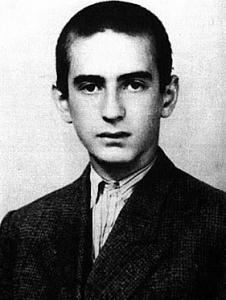

Elie Wiesel, witness to the Holocaust, lost his faith in God. He also lost his faith in humanity.

The stories in his memoir Night are devastating:

- Young Jews striking a “mad woman” on the head to shut her up.

- The inversion of the father-child relationship as his father declines to a helpless state and the teenager becomes his resentful caregiver. “Here there are no fathers, no brothers, no friends,” a Kapo tells him. “Everyone lives and dies for himself alone.”

- A Rabbi’s son who races ahead to lose his father during the march in the blizzard. The father is just dead weight that reduces the son’s chance for survival.

- As a prisoner is about to be hanged, Juliek says to Elie, “Do you think this ceremony will be over soon? I’m hungry.” Wiesel himself describes tasting excellent soup immediately after looking at a dead boy in the face.

- On the train to the camp, dozens of starving men fought each other to the death for a few crumbs.

By the end, when Wiesel describes himself in the mirror as “a corpse” gazing back at himself, it is apparent that Wiesel’s spirit died during the Holocaust, that he never really started living again, that his faith in others died. His assessment wasn’t too far off. The world in fact persisted in its penchant for evil in the most violent century of history: genocide in Rwanda, Sudan, and Bosnia; Pol Pot in Cambodia; Mao in China.

But these are far-off places. Such things surely couldn’t happen “here.” Wiesel begged to differ. None of the people in the village, including Wiesel, believed an old man who had escaped from a camp to tell of his experience. They believed that humanity was not capable of such horrors. They had many chances to leave, but they could not be convinced that this was happening.

It’s easy to “other” evil in the world. It’s an urban problem. It’s a Muslim problem. It’s an immigrant problem. We hardly need reminders now. A so-called “colorblind” society results in wildly disproportionate violence against blacks. The vagaries of capitalism and industrialization result in disenchanted Westerners who resort to mass murder in the name of Allah.

Wiesel shows the limits of perfectability. Given the right conditions, we could be the Nazi soldier who bake Jews in the oven. Given the right conditions, we could be the Jew who leaves his father in the snow to save himself.

A short epilogue: Any faith in humanity that Wiesel might have recovered in the decades after the Holocaust was lost near the end of his life. He was victimized by Bernie Madoff, the investment advisor and perpetrator of the largest Ponzi scheme in American history. Wiesel lost $37 million in personal savings earned from book sales and lectures. He also lost $20 from his charitable nonprofit organization. Soon after Madoff was arrested, Wiesel was asked if he could forgive Madoff. After a lengthy pause, he murmured to himself, “Could I ever forgive him?” Finally, to a burst of applause, he said firmly “No.”