Over the weekend, I noticed a tweet from the Christian writer Rachel Held Evans, on an airplane getting ready to travel somewhere. “First time flying for the couple in the row in front of me,” she reported. “They whooped and hollered during takeoff like they were on an amusement park ride. Kinda refreshing after a day with calloused business travelers. Flying really is a marvel.”

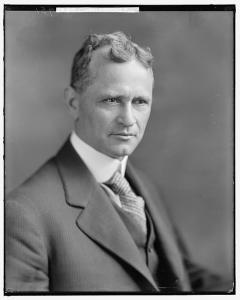

I only fly a few times a year, but I’m probably more in the “calloused” category. Aviation is just another means of getting around: an inconvenient convenience that rarely feels all that marvelous. I’m in the middle of researching a spiritual biography of Charles Lindbergh, but the air journey that made him not just a celebrity but the “new Christ” is now routine. I’ve flown across the Atlantic Ocean a dozen times without finding anything all that transcendent in the experience. (Mostly I just wish that I could fall asleep on airplanes.)

So, like Evans watching her first-time flyers, I’ve found it “kinda refreshing” to read early American responses to the sight of Orville Wright and other aviation pioneers taking to the skies. “Never,” reported one Chicago pastor in 1910, perhaps wistfully (or resentfully), “have I seen such a look of wonder in the faces of a multitude.” Earlier that year, a visitor to an air meet in Los Angeles described the feeling of anticipation as tens of thousands of people waited for planes to take off: “It is the moment of miracle,” he wrote.

“And so it was at the first demonstration of each airplane,” observes historian Joseph Corn. “The event was both unexplainable and unbelievable. Unlike most other phenomena encountered in daily life, there seemed to be no words to describe an airplane flight except ones borrowed from the supernatural and mystical realms…. At last the earthly shackles that for millennia seemed so restricting had been broken. In an airplane one could now fly anywhere, perhaps, thought some, even to heaven!”

(In the days when he was just a barnstorming young pilot, Lindbergh would take people on a short flight for a few dollars. Once in Mississippi, Corn mentions, an “elderly black woman came up to him and, in total seriousness, asked him how much he would charge to fly her to heaven and leave her there.”)

In his book The Winged Gospel, Corn explains that many Americans, “[f]rom the first ‘ moment of miracle’ when they first saw an airplane leave the ground through Lindbergh and down to the mid-twentieth century… perceived the conquest of the skies as a profoundly spiritual activity, somehow linked with the divine and the supernatural.” The most enthusiastic version of this response — what was called “airmindedness” — grew into a “popular techno-religion” with its own message of transformation: “Like the Christian gospels, the gospel of aviation held out a glorious promise, that of a great new day in human affairs once airplanes brought a true air age.”

Corn describes a kind of spectrum of “technological messianism” associated with the messengers of this “gospel.” The most grounded (so to speak) of these evangelists simply promised beneficial social change. Aviation, for example, could become a more democratic form of transportation than the railroads, which embodied corporate control and corruption for many. For some women and African Americans, the sky constituted a new frontier, free from their society’s structures of inequality and oppression. Others (including, for a time, Lindbergh) expected aviation to inaugurate world peace and international cooperation.

Corn describes a kind of spectrum of “technological messianism” associated with the messengers of this “gospel.” The most grounded (so to speak) of these evangelists simply promised beneficial social change. Aviation, for example, could become a more democratic form of transportation than the railroads, which embodied corporate control and corruption for many. For some women and African Americans, the sky constituted a new frontier, free from their society’s structures of inequality and oppression. Others (including, for a time, Lindbergh) expected aviation to inaugurate world peace and international cooperation.

Tellingly, Britons and Europeans — though enthusiastic about aviation — never embraced anything like the “winged gospel.” While Americans dreamed of an age of perpetual peace, pre-WWI English writers like H.G. Wells and Harold F. Wyatt proved far more prescient in their predictions of airpower expanding warfare far beyond the confines of traditional battlefields.

Still more remarkably, America’s most most radical advocates of airmindedness “read the new sign in the heavens as portending nothing less than a great leap forward in human evolution, leading to a species physically and even spiritually transformed as a result of flying.” (At some point in my biography of Lindbergh, I’m sure I’ll come back to this notion in light of the aviator’s interest in eugenics.)

For example, the baseball player-turned-aeronautical publisher Alfred W. Lawson believed that God called him to evangelize for flight. Having earlier written a Christian utopian novel called Born Again, in 1916 he published “Natural Prophecies,” an article envisioning a distant day when aviation would have brought about the evolution of an aerial superhuman. “Residing permanently in the heavens,” concludes Corn, “[Lawson’s] Alti-man was nothing if not a god. He epitomized the winged gospel’s greatest hope: mere mortals, mounted on self-made mechanical wings, might fly free of all earthly constraints and become angelic and divine.”

However uncomfortable Lawson’s “prophecy” may make Christian readers, Corn argues that Americans’ uniquely messianic understanding of aviation was a result of their religious history. In general, “Christianity bequeathed a cargo of assumptions and rhetorical patterns which Americans, even non-believers, were hard-pressed not to load onto the newly invented flying machine.” But Corn thinks that the evangelical revivalism of the 19th century — coinciding as it did with America’s industrial revolution — did still more to pave the way for the “winged gospel”:

Preachers extolled the prospects of replicating heavenly perfection right on earth, if only people had faith… The combination of an optimistic, this-worldly religion with an industrial revolution encouraged many to view secular developments as evidence of religious progress. Machinery became a “gospel worker,” and devices of iron and steel seemed pregnant with great moral and spiritual implications.

The “religious rhetoric” of this era “prepared people to greet the airplane as a heavenly gift in the twentieth century,” as adults heard sermons “that similarly confused flight as a mode of transportation and as a spiritual accomplishment” and children memorized poems like the following:

In joy and glory

We shall rise

To be with Christ

Above the skies.

Corn struggles not to overreach, often seeming to attribute airminded enthusiasm to “Americans” as a general category without offering more than a few, perhaps exceptional supporting examples. But it seems undeniable that Americans “inevitably borrowed from” a religion “where angels flew and the heavens constituted the divine sanctuary of God” in order to explain the meaning of aviation. And I’m now doubly curious to learn more about the response of pastors and theologians to the achievements of Lindbergh: Did they find the “winged gospel” a threat to the Good News of Christ, or a useful complement to it?