In Kevin Kwan’s Crazy Rich Asians trilogy, a wealthy family in Singapore considers a real estate deal that is so financially lucrative, it almost seems divinely ordained. A developer is offering to purchase the family’s property for $3.3 billion in order to build “Zion Estates,” described as “A LUXURY CHRISTIAN COMMUNITY.” A brochure offers details about the vision for the project:

Imagine an exclusive gated community for high-net-worth families who share in the blessings of the Holy Spirit. Ninety-nine splendid villas, inspired by the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, ranging from 5,000 to 15,000 square feet on half-acre lots will surround Galilee, a glorious artificial lagoon complete with the world’s tallest man-made waterfall supplied only with water imported from the River Jordan. At the heart of the community lies the Twelve Apostles, a unique twelve-hole golf course designed by our faithful brother Tiger Woods, and an exquisite clubhouse—the King David—which will boast a trinity of world-class restaurants operated by Michelin-starred chefs, along with Jericho, sure to become Singapore’s most decadent spa and state-of-the-art health club. Come to Zion—live abundantly and be saved.

The family is enthusiastic about the proposal, with the exception of one person, who scolds his relatives after he reads the pamphlet. “In case you’ve forgotten,” he says, “Jesus served the poor.”

“Of course he did. What’s your point?” his aunt responds. “Jesus said, ‘To grow rich is glorious.’ ”

The nephew grows exasperated. “Actually,” he says, “Deng Xiaoping, the late Communist leader of China, said that!”

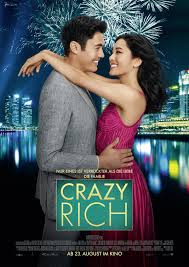

Whether the teaching comes from Jesus or Deng Xiaoping doesn’t really matter to the family—either way, they consider growing rich to be glorious. And they are, indeed, gloriously rich. The Crazy Rich Asians novels—the first of which was adapted into a film that topped the box office this past weekend—is a story about Asian families that are very rich—crazy rich, to be precise. Both the novels and the movie are filled with seductive details of the opulence of the new Gilded Age: haute couture, rare sports cars, magnificent jewelry, and luxury watches. But while the Crazy Rich Asian novels appear at first glance to be little more than a frivolous comedy about the glitterati, the trilogy is, in fact, a satire that lodges a compelling critique of the excesses of wealth and power among Asia’s richest families.

The target of Kwan’s critique isn’t merely Asian people who are crazy rich—it’s Asian people who are crazy rich and Christian. Amid the discussion of Rolexes and Rolls-Royces, religion is a recurrent theme in the Crazy Rich Asians trilogy. This is partly a reflection of the novels’ setting. Singapore is an important financial center with the highest density of millionaires in Asia, and it’s also a religious hub with such a vibrant Christian presence that Bill Graham referred to it as “the Antioch of Asia.” Singapore’s prominence as a center of both capitalism and Christianity serves as an important backdrop to Kwan’s satirical portrait of the Asian elite. Through his depiction of the self-serving religious practices of Singapore’s snobby upper class, Kwan assails the multiple ways that wealthy Christians exploit religion for their own economic, social, and cultural gain.

“Communing with Christ at a higher level”

In the world of Crazy Rich Asians, religion is an important indicator of social status and a valuable tool for advancement, with religious institutions functioning less as sites for sincere spiritual growth than as settings for producing economic and social power. To be sure, the idea that religion is a form of symbolic capital—“spiritual capital,” as some have described it—is not unique to twenty-first century Singapore; similar dynamics have been at work in other times and places. The historian Thomas Rzeznik points out, for example, that religious identities, practices, and beliefs were important markers of class status in industrial America. Likewise, Robbie Goh, who researches Christianity in Southeast Asia, observes that in modern-day Singapore, there are noticeable patterns in religious affiliation and class status—mainline Protestants, in particular, are typically better educated, English-speaking, and more socio-economically privileged. Context matters, of course, and in Singapore, the spiritual capital of religious belonging is shaped powerfully by the island’s history of Western colonialism, as well as the past and present reality of economic inequality and ethnic and racial stratification.

In Kwan’s novels, elite families show off their affluence and aristocratic pedigree by highlighting their Protestant heritage. When one wealthy woman discovers that her granddaughter is reading Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha, she expresses dismay that the child is reading about Buddha. “You’re a Christian,” the grandmother admonishes, “and don’t forget that we come from a very distinguished long line of Methodists.” As the grandmother’s response reveals, she considers it important to identify as Protestant, and it’s just as important to distance the family from non-Christian religions, which the novel’s crazy rich characters associate with low economic, social, and racial status. Similar impulses and prejudices are on display when the matriarch of one of Singapore’s richest families shocks her relatives by declaring that she is a Jain. After learning that Jainism is related to Hinduism, one of the matriarch’s daughters nearly has a meltdown. “Hinduism?” she cries. “You can’t possibly be Hindu. My goodness, our laundry maids are Hindu! Don’t say you are a Hindu, Mummy—it would absolutely break my heart!”

Prestigious educational institutions serve to further reinforce the link between Protestant Christianity and high social status. Kwan portrays a world where the children of the rich follow a carefully prescribed upbringing that involves, among other things, attending a premier missionary school and spending weekends doing Christian Youth Fellowship activities. Those who harbor social ambitions but are not born into established elite families seek to place their children in these Christian institutions, even if they are not themselves Christian. One of these social strivers is Annabel, an arriviste from Ürümqi who migrates to Singapore along with other “newly minted Mainlanders.” Aspiring to raise her child among “people of breeding and taste,” she enrolls her daughter in Methodist Girls’ School while also “forcing her to go to Youth Fellowship at First Methodist even though they were Buddhists.” Another character, Charlie, also hails from a new money family, and his parents make similarly calculated decisions for their son, who also joins the Methodist church youth group. Though Charlie and his family are Taoists, “his mother had forced all of them to attend First Methodist so they could mix with a ritzier crowd.”

In the Crazy Rich Asians trilogy, the desire to “mix with a ritzier crowd” motivates parvenu families to strategize not only about schools and social activities, but also churches and Bible studies, where important social networks are established. The importance of churches as sites of status and power is most apparent in an episode centered on Kitty Pong, a former porn star who marries a wealthy heir and seeks to rehabilitate her public image in order to gain acceptance by Asia’s high society. A consultant who specializes in advising upstarts like Kitty instructs her to join Stratosphere Church. “Your true spiritual affiliations do not concern me,” the consultant tells Kitty, “it does not matter to me if you are Taoist, Daoist, Buddhist, or worship Meryl Streep—but it is absolutely essential that you become a regular praying, tithing, communion-taking, hands-in-the–air-waving, Bible-study-fellowship-attending member of this church.” (The consultant notes that the church offers “the added bonus of ensuring that you will be qualified for burial at the most coveted Christian cemetery on Hong Kong Island, rather than having to suffer the eternal humiliation of being interred at one of those lesser cemeteries on the Kowloon side.”)

The consultant eventually brings Kitty to attend Sunday services at Stratosphere Church, which meets at the top of a glamorous skyscraper called Glory Tower. As the consultant explains, this invitation-only church—the motto of which is “Communing with Christ at a Higher Level”—is “the most exclusive church in Hong Kong” and the pet project of billionaire Pentecostal sisters. “Not only is it the highest church in the world, at ninety-nine storys above the earth, but it boasts more members on the South China Morning Post’s rich list than any other private club on the island,” the consultant gushes. Aware of the significance of the occasion and knowing little about Christianity, Kitty is nervous during the visit, but she finds that worshipping at Stratosphere is an uplifting experience. She is enthralled by the warm hugs shared among strangers, the praise band led by a “hunky rock god,” and the breathtaking view of Hong Kong that serves as a backdrop for their tear-filled praying and hymn-singing. “If this wasn’t heaven on earth, what was?” Kitty asks herself.

But the consultant’s primary purpose at Stratosphere Church is not, in fact, praying or hymn-singing during the service—it’s networking after the service. “Kitty, the whole reason I brought you here is so you can socialize with these people over coffee and cake,” she says. “This is the main event. Many of the members are the younger generation of Hong Kong old-guard families, and this is the best chance you have of getting to know them.” Her goal for the initial church coffee hour is for Kitty to get invited to join one of the Bible study groups with daughters from the island’s top families. Kitty ultimately fails miserably at this task, but not before engaging in an enthusiastic discussion with some prominent church ladies about the lesson of the day’s sermon—the possibility that “anyone with a willing heart can be born again.” On the surface, Kitty appears to discuss being “born again” as a religious transformation, but she is articulating desires that are, in truth, less than divine. For her, visiting Stratosphere Church and becoming a born-again Christian is a way to achieve her goal of being “born again” socially, as a fully accepted member of Asia’s aristocracy.

Although she makes valiant efforts to gain acceptance among the elite evangelical crowd, Kitty is actually Buddhist, and like Annabel and Charlie, she’s willing to join a Christian church because doing so helps her to secure a place in the most privileged social circles. Characters like Kitty, Annabel, and Charlie are significant to Kwan’s satirical portrait of Asian high society; through them, Kwan offers a critique of wealthy Asians’ superficial and instrumental embrace of Christianity. Viewed more generously, this approach might simply be considered flexible, and it’s perhaps not inconsistent with how Asian elites have navigated other matters of political and social belonging in real life. According to the anthropologist Aihwa Ong, wealthy Asian families practice what she calls “flexible citizenship.” Responding “fluidly and opportunistically to changing political-economic conditions,” elite families live transnationally, seeking “to both circumvent and benefit from different nation-state regimes by selecting different sites for investments, work, and family relocation.” In the Crazy Rich Asians novels, Kwan caricatures Asian elites who pursue a religious version of “flexible citizenship,” wherein Protestant identity and church membership are similarly fluid and opportunistic, and religion functions as a form of symbolic capital that is adaptable, strategic, and focused solely on increasing economic, social, and cultural advantage.

“Being Mother Teresa is good for business”

In Flexible Citizenship, Ong draws on Pierre Bourdieu’s work on social distinction to show how wealthy Asian families embrace symbolic capital not only to enhance their social standing, but also to obscure the unpleasant ways that they acquire wealth and power. “Symbolic capital thus invites honor while disguising its links with the kinds of accumulation we often associate with crass money dealing,” she writes. “As an ideological system of taste and prestige, symbolic capital reproduces the established social order and conceals relations of domination.” In the Crazy Rich Asians novels, religion is especially valuable in this regard. For the arrogant and avaricious people at the center of Kwan’s story, Christianity offers convenient cover for the sins of contemporary capitalism.

For starters, there are the sins of vanity and pride. The well-heeled women in the Crazy Rich Asians trilogy spend outrageous sums of money on fine jewelry and high fashion, which is the focus of their attention even at ostensibly religious gatherings. Eleanor, for example, enjoys going to Bible study at the home of her friend Carol Tai, in part because it presents an opportunity for her to inspect Carol’s newest jewelry; Eleanor, being a good Christian women, especially admires the delicately designed Harry Winston crosses. Carol is also well known in this social circle for her involvement with a charity called “Christian Helpers,” which sponsors events that are among the most important fashion events of the year. One woman, Francesca, brags about her extensive collection of Chanel resort wear, the acquisition of which she sees as an act of generous Christian charity. “I bought this season’s entire collection at Carol Tai’s Christian Helpers fashion benefit,” she announces smugly to her friends.

For starters, there are the sins of vanity and pride. The well-heeled women in the Crazy Rich Asians trilogy spend outrageous sums of money on fine jewelry and high fashion, which is the focus of their attention even at ostensibly religious gatherings. Eleanor, for example, enjoys going to Bible study at the home of her friend Carol Tai, in part because it presents an opportunity for her to inspect Carol’s newest jewelry; Eleanor, being a good Christian women, especially admires the delicately designed Harry Winston crosses. Carol is also well known in this social circle for her involvement with a charity called “Christian Helpers,” which sponsors events that are among the most important fashion events of the year. One woman, Francesca, brags about her extensive collection of Chanel resort wear, the acquisition of which she sees as an act of generous Christian charity. “I bought this season’s entire collection at Carol Tai’s Christian Helpers fashion benefit,” she announces smugly to her friends.

Among all of the characters in Kwans’ novels, Carol is the most ardent Christian, and it’s clear that her piety is partly a calculated effort to conceal her family’s well-known history of greed. Her husband “made his first fortune the dirty way by bringing down Loong Ha Bank in the early eighties.” Since then, Carol has done so much charitable work and hosted so many weekly Bible studies that she has “burnished the Tai name into one of respectability.” Carol fills her schedule with numerous charity galas—“as any good born-again Christian should,” she reasons. But perhaps more important than the spirit of Christian benevolence is the power of the bottom line. Her husband insists that she do charity work since he believes that “being Mother Teresa is good for business.”

That Christian piety can put a respectable gloss on capitalist greed is a deceit that Kwan parodies from the very beginning of Crazy Rich Asians. In one of the most memorable episodes in the novels, Carol’s husband interrupts the women’s weekly Bible study with a shocking announcement: a secret source informed him about developments in China that will cause the imminent collapse of the stock for a company called Sina Land. Pandemonium ensues, as the women cast aside their Bibles and frantically call their stockbrokers to dump their Sina Land shares. Amid this chaos, Carol raises her arms and begins to pray:

Oh Jesus, our personal lord and savior, blessed be your name. We come to you humbly asking for your forgiveness today, as we have all sinned against you. Thank you for showering your blessings upon us. Thank you Lord Jesus for the fellowship that we shared today, for the nourishing food we enjoyed, for the power of your holy word. Please watch over dear Sister Eleanor, Sister Lorena, Sister Daisy, and Sister Nadine, as they try to sell their Sina Land shares …

With its intertwining of Chanel and charity work and scripture and stocks, Carol’s life reveals a central assumption: Christianity and capitalism go perfectly together.

In his satirical portrait of elite Asian families, Kwan has much to lampoon: their snobbery, vanity, greed, and extravagance. But what makes the Crazy Rich Asians novels so unusual is their attention to the religious lives of Asian elites–the false piety, the imbecilic hypocrisy, and the uses and abuses of Christianity to hoard money and power. To be sure, it’s easy to laugh at characters who are motivated by such naked avarice and ambition, especially when they confuse the teachings of Jesus and Deng Xiaoping. But the critique in Kwan’s novels ultimately isn’t limited to Asian people, rich people, or crazy people. The main lessons—that people can distort and exploit religion for their own ends, that religion can conceal the worst of human sins, and that religious institutions can bolster inequality, materialism, and other social wrongs—apply to all people of faith, wherever they are located, however rich or poor or crazy they are.