I recently fulfilled a lifetime ambition with a visit to the city of Ravenna, one of the world’s greatest centers of Christian art. I am still floored by the experience, so excuse me if I try to process it by means of writing.

If you have ever opened a book about early Christian or medieval history, at least some of the illustrations were likely taken from a Ravenna location. In this column I will describe the city and just why it became so astonishingly significant, before discussing its artistic treasures in more detail.

Last time, I described how the Western Roman Emperors moved their political capital to Ravenna, which in various forms retained that pivotal role from the fifth century through the eighth. Although it became an Ostrogothic capital in the late fifth century, the Romans returned in the 530s. In political and military terms, Ravenna has a fair claim to rank as the most significant urban center in Western Europe for some centuries. It lost that role in the eighth century and fell into relative obscurity – although it did become the residence of certain quite well known Italians, such as, um, Dante Aligheri, who is buried there. No, really.

Last time, I described how the Western Roman Emperors moved their political capital to Ravenna, which in various forms retained that pivotal role from the fifth century through the eighth. Although it became an Ostrogothic capital in the late fifth century, the Romans returned in the 530s. In political and military terms, Ravenna has a fair claim to rank as the most significant urban center in Western Europe for some centuries. It lost that role in the eighth century and fell into relative obscurity – although it did become the residence of certain quite well known Italians, such as, um, Dante Aligheri, who is buried there. No, really.

Roman Emperors and their representatives adorned Ravenna with magnificent churches and palaces. In the High Middle Ages or Renaissance, a diminished Ravenna could not compete with better known cities like Florence or Venice, which was actually wonderful news as later generations lacked the means or inclination to tear down their ancient, unfashionable, churches and replace them with fine new structures. As a result, Ravenna remains one of the largest centers to be found anywhere of late Roman and “Byzantine” art. I dislike the word Byzantine, which nobody actually used in the Middle Ages: it was still the Roman Empire, the people were Romans, and called themselves Romans. But with that caveat, I will use the B-word on occasion.

Visiting Ravenna is more complex than exploring other historic cities, because there is no one single star attraction. You don’t just find the main cathedral, the Duomo, and join a tour. Ravenna has no fewer than eight (!) separate structures listed as UNESCO World Heritage sites, and you need transportation to get to them all. These are the main complexes:

Orthodox Baptistery or Baptistery of Neon (c. 430) and Archiepiscopal Chapel (c. 500)

Basilica of San Vitale (548) and Mausoleum of Galla Placidia (c. 430)

Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo (c. 500)

Arian Baptistery (c. 500)

Basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe (549)

Less central to my discussion here is the Mausoleum of Theoderic (520).

All these dates have a good deal of flexibility, as work was still being added centuries after the formal inauguration. You can actually see a good deal of censorship and rewriting, as various kings and rulers were erased from the record, portraits were retitled, and their works reconceived, often clumsily. Ravenna remained a work in progress for some 350 years.

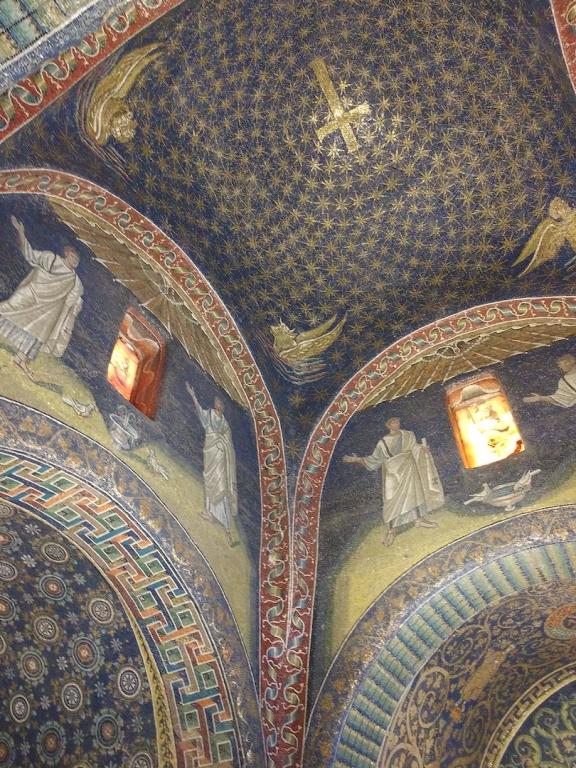

Although it is not necessarily the absolute peak of achievement, the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia still stuns. It is usually associated with that extraordinary woman who dominated the Western Empire between about 420 and 450, although we have no exact idea what its function was, or whether in fact it was intended for funerary purposes. The “mausoleum” itself is a treasure house, but we might err by describing it exclusively as Christian art. It is of course the elite work of secular Late Antiquity, repurposed for Christian themes and messages.

Although it is not necessarily the absolute peak of achievement, the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia still stuns. It is usually associated with that extraordinary woman who dominated the Western Empire between about 420 and 450, although we have no exact idea what its function was, or whether in fact it was intended for funerary purposes. The “mausoleum” itself is a treasure house, but we might err by describing it exclusively as Christian art. It is of course the elite work of secular Late Antiquity, repurposed for Christian themes and messages.

Several of the site’s images have become very famous, including depiction of Biblical and apocalyptic themes, of saints, and of stories that we frankly just do not understand. Here is one beautiful but cryptic example:

Is this a saint threatened with martyrdom by burning, perhaps St. Lawrence with his gridiron? I quote Wikipedia:

The art historian Gillian Mackie argues that this panel represents the Spanish St. Vincent of Saragossa ….. The panel seems to be an illustration of the poem about St. Vincent in Prudentius’s fifth century Passio Sancti Vincent Martyris. In the poem St. Vincent is ordered to disclose his sacred books to be burned. This explains the cupboard containing the Gospels.

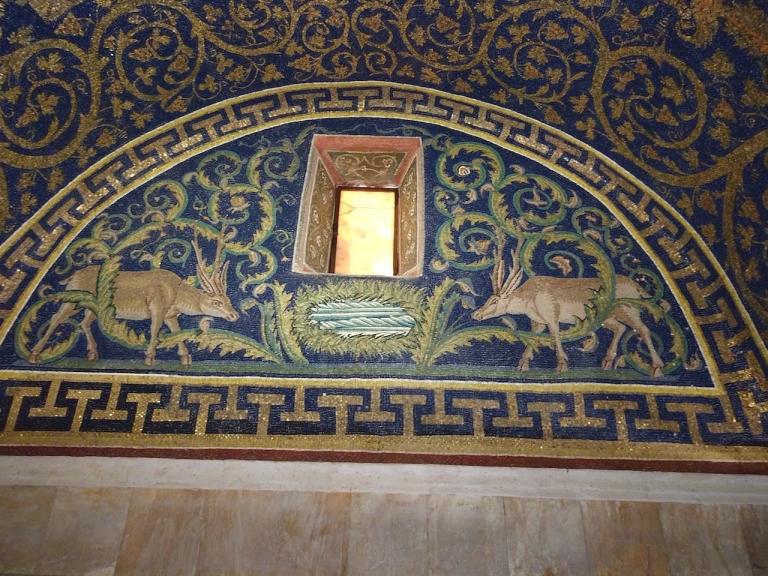

I especially like this next image, which illustrates the opening of Psalm 42, “As the deer pants for streams of water, so my soul pants for you, my God.” And right there are the deer.

As you will appreciate, the level of specific detail in this “mausoleum” suggests an elite patron or patrons very thoroughly acquainted with Christian and Biblical tradition, and with contemporary Christian culture, possibly viewed through a Spanish lens. Galla Placidia?

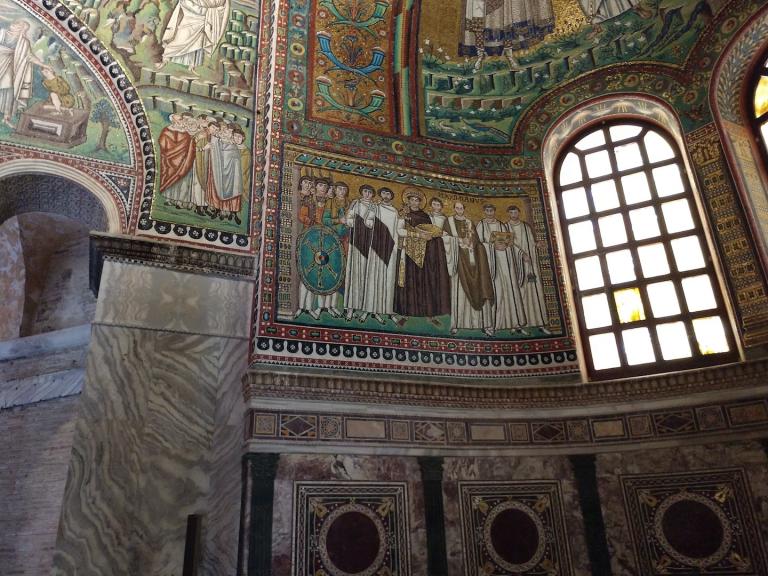

Ravenna also gives us a wonderful sense of what everyday Christian life and liturgy must have looked like in this era. Several of the main sites include depictions of what would have been the interiors of churches, giving us an excellent sense of what hey might have looked like – how for instance gospel books were displayed.

More generally, if you want to see the visual world of Late Antiquity, it is laid out before you here , much more comprehensively than in most of the once far greater cities of the Eastern Empire itself. Put another way, this is where you go if you want to see the visual imagery that would have been familiar to such cornerstones of the Western Cristian tradition as Augustine and Gregory the Great, Benedict and Cassiodorus. This was the visionary world before their eyes as they contemplated, and as they wrote.

The range of sources on Ravenna is enormous, but by far the best current work is Deborah Mauskopf Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity (Cambridge 2010). I enjoyed an intelligent summary of the city and its works by Patrick Comerford.

CREDITS: I took all the photographs myself, with my cellphone.