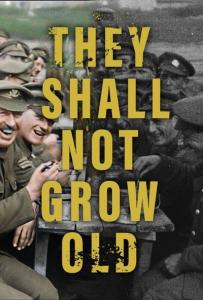

Yesterday afternoon I joined a theater-full of fellow mall-goers in watching Peter Jackson’s latest marvel of digital age filmmaking: a minutely-detailed, lavishly produced, 3D epic that tells the story of a tragic war. No, you didn’t miss a special re-release from the Lord of the Rings or Hobbit trilogies. Jackson’s newest movie is a documentary about World War I. Entitled They Shall Not Grow Old, it’s wonderful — for all the reasons I had reservations about Jackson’s previous work.

Technically, They Shall Not Grow Old is as inventive as Jackson’s earlier work, but also surprisingly meticulous as a work of historical preservation and synthesis. (Our special screening included a half-hour making-of special in which Jackson took us behind the scenes of the project. If you can’t see that, read yesterday’s piece in the New York Times.) The project started with 100 hours of black-and-white film from the Imperial War Museum — much of it cracked, shrunken, overexposed, blackened, or duplicated multiple times. If all Jackson and his team had done was to spend three years digitally restoring all that film, it still would have been a significant feat. And at first, that’s what They Shall Not Grow Old looks like: a crisp but conventional account of why Britons joined up in August 1914 and how strict sergeants turned them into soldiers.

But as those new recruits reach the Western Front, something dramatic happens. You suddenly see the second half of Jackson’s experiment: colorizing film, converting everything to 3D, and — most strikingly — retiming the footage to make the soldiers’ movements seem less, well, silent movie-ish.

It feels like you’ve been watching a BBC documentary, then suddenly find yourself on the other side of the TV screen, staring back at Tommies in Flanders who look like they don’t know what to make of you.

(As Jackson explains, that’s because — unlike us — they weren’t used to being filmed. One literally falls off the side of a road staring at the camera, and more than once we hear one soldier tell another, “We’re in the pictures, mate!” So let’s also use Jackson’s film as an excuse to pay new tribute to The Battle of the Somme, the 74-minute documentary filmed on the Western Front by Geoffrey Malins and John McDowell and released in England five weeks into a 1916 battle that lasted over four months and caused over a million casualties. That film is one of the chief sources of footage for They Shall Not Grow Old, and seemed as powerful in 1916 as Jackson’s documentary does in 2018. I wrote about it several years ago at my personal blog.)

The marvels of They Shall Not Grow Old extend from sight to sound. Not only does the film feature the sound editing and effects that earned Jackson’s team several Oscar nominations for their previous work (the sucking sound of viscous Flemish mud and the whistle of artillery shells are especially effective), but it weaves in the voices of soldiers through two ingenious means. First, Jackson’s team took 1960s BBC interviews with WWI veterans and used those reminiscences in place of narration. Second, he hired forensic lip readers to figure out what soldiers had been saying while being filmed back in 1914-1918, then voice actors (from the same regions as the soldiers’ regiments) brought those words — mundane and otherwise — to life.

Again, it’s as technically impressive as anything Jackson did with his interpretation of WWI veteran J.R.R. Tolkien’s most famous stories. But what I liked least about the Lord of the Ring series — and what made me enjoy the first film of The Hobbit series so little that I skipped the second and third — was the way that Jackson used that brilliance to dramatize warfare. For if Tolkien did mean Lord of the Rings as a comment on the industrialized war he had seen on the Western Front, then Jackson’s computer-generated battle scenes rang especially hollow: mass-animated men, elves, dwarves, and orcs existed solely as anonymous fodder for Somme-like slaughter. (The effect was even more pronounced in the video game-like Hobbit. Though there were other reasons that those films fell so flat…) As good as Jackson was at dramatizing the mounting toll of an epic quest on individual characters, I almost always felt like he made war itself seem mechanical, two-dimensional.

So here’s what really made me look forward to seeing They Shall Not Grow Old: every review I’d read emphasized how Jackson’s technical skill amplified the humanity of these long-dead soldiers. Guy Lodge, Variety: “Years after the gratuitous exertions of his ‘Hobbit’ trilogy, Jackson has found fresh, humane purpose to his ambitious technical artistry…” Peter Bradshaw, The Guardian: “The effect is electrifying. The soldiers are returned to an eerie, hyperreal kind of life in front of our eyes, like ghosts or figures summoned up in a seance. The faces are unforgettable.”

Indeed they are. “You can see the fear, you can see the humor,” marveled Jackson, as he studied the old footage. He went on to explain that the “most interesting stuff was their mundane lives.” We see soldiers marched into church (“it didn’t matter your religion,” one remembered), brewing tea with machine gun-heated water, and, um, figuring out how to relieve themselves without latrines.

But we also see dead bodies. Lots of them. While Jackson sought to stitch together “an accurate generic experience” of trench combat on the Western Front, the lack of actual footage of such fighting “forced [his team] to do some interesting things.” So while he used sketches from a magazine called The War Illustrated to dramatize combat, that stretch of the film zeroes in on the cost of war. We zoom in on soldiers we’ve met earlier, then Jackson cuts to shockingly gruesome images of mutilated, decaying corpses, suggesting the fate of those who didn’t survive to recount their harrowing experiences.

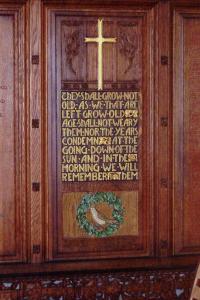

The soldiers of They Shall Not Grow Old “mingle not with their laughing comrades again,” wrote Laurence Binyon in the poem that gave Jackson his title. “They sit no more at familiar tables of home; / They have no lot in our labour of the day-time; / They sleep beyond England’s foam.” Binyon hoped that they would nonetheless live on in the memory of the English people, where “Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.” But as generations pass, film and other artifacts erode, and attention shifts elsewhere, it takes the ongoing effort of historians, archivists, and artists like Jackson to reawaken that kind of remembering.

Your next chance to see Jackson’s documentary will be at selected theaters on December 27th. Don’t miss it!