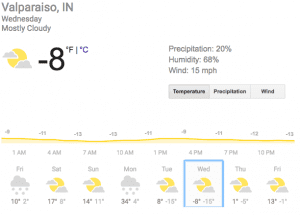

But we expect it to be—don’t we? What is the big deal about winter if we are expecting it to be cold anyway?

But we expect it to be—don’t we? What is the big deal about winter if we are expecting it to be cold anyway?

That question opens historical puzzles. As scholars of the American colonies have recognized for decades, settlers from Europe and the investors who sent them supposed the climate of what became the United States would be different from what it turned out to be. Cold winters become an historical question not only as we wonder why one was longer or frostier than another, but most of all in terms of the way those living at the time reacted to those events. Of course, how they reacted is a matter of thought as well as action. What we do about a blizzard depends not only on where we have to go or how we get warm, but what we think is going to happen. And what English settlers thought sometimes was quite different from what they found. This disconnect was perhaps especially formative in the experience of colonial New England, where harsh long winters were much more severe than anticipated.

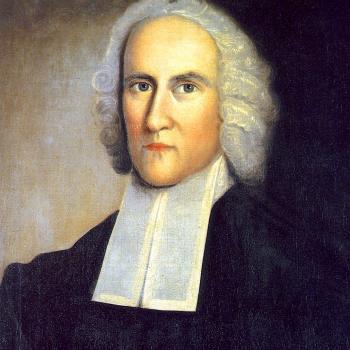

What winter was like is not only a question for history in general but also for religious history. The founders of colonies in New Engladn brought with them a way of seeing the world shaped by a certain strain of Christianity and a particular view of Providence. That is, they assumed God caused events, not only private ones involving redemption and grace, or ecclesial ones, like the growth of a church, but events we might otherwise attribute to nature. Storms, floods, droughts, and snow might show God’s responses to human action. New England Puritans held a sense of themselves as a people in covenant with God. Corporately, they tried to honor God in their planting and building, buying and selling, thinking God would not only bless or punish individuals but the people as a whole. Thus, a reasonable consistency explains why these settlers would see mild weather and good harvests as God’s blessing, and biting winter as a sign of divine disfavor. Pious judge and diarist Samuel Sewall wrote,

Once more! Our God, vouchsafe to Shine:

Tame Thou the Rigour of our Clime.

In an influential 1984 article, historian Karen Ordahl Kupperman invited scholars to consider the climate confronting New England settlers, from which they strove to make spiritual sense. We can see that their winters actually were harsher than what they or we might have found normal because of what historians and students of climate recognize as a Little Ice Age, whose severest period coincided with European settlement of American colonies. Puritan thundering about weather, then, might not be fiery hyperbole, but reflect conditions they observed.

Building on insights like Kupperman’s, Ohio State professor Sam White’s 2017 book, A Cold Welcome, goes further to explain how hot and cold were not what was expected in the centuries around American colonization, and how human activity aggravated and responded to climate events.

Icy blasts may make it feel urgent to retreat indoors to think through climate and human imagination in historical terms. The weather, its changes, our expectations, and our agency in its vagaries, are part of the American fabric from the first.