In part because the gospel accounts have so little to say about Holy Saturday, in part because I often wake up this day with little to do, I often find myself speculating. Not necessarily What happened? in between Crucifixion and Resurrection — someone else can write a post about the Harrowing of Hell — but What were people thinking? What was on the minds of the participants as the dramatic events of Good Friday started to turn from vivid experience to fading memory?

How their minds must have churned as the Jewish followers of Jesus “rested according to the commandment” (Lk 23:56b) of a God who seemed to have forsaken his Son. I wonder if that was the first Sabbath in his life that Peter wished he could hold a fishing net in his calloused hands, when he would have given anything to forget the sound of his own voice denying his Savior. Did Matthew and John wish they could erase from their minds’ eyes the terrible events that they would eventually write down? Could they have known then, when there was no good news to tell, that they would publish gospels?

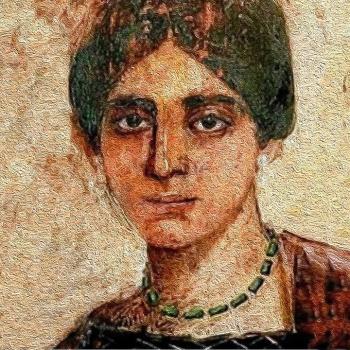

Did the scent of the funereal spices and ointments the women had prepared remind Jesus’ mother of the Magi’s myrrh, as she pondered for the thousandth time Simeon’s words (“…a sword will pierce your own soul too”)? Was Martha, remembering the stench of her brother’s once-decaying body and worried and distracted as ever, itching to return to the tomb and perfume Jesus?

Perhaps out of a surfeit of historical curiosity, I’m especially prone to speculate about the disciples about whom we know even less.

If all we know of Simon the Zealot from his brief mentions in Luke–Acts are his politics, then I imagine him following a downward spiral. Having hoped to see Roman imperium replaced by Jewish independence, how excited he must have been to see Jesus enter Jerusalem, David’s capital, in a kingly procession. How easy it would have been for him to forget that Jesus was going to Jerusalem “to be mocked and flogged and crucified.” How confused that patriot must have been when his king bathed his feet, like the lowest of slaves. How angry he must have been when his king meekly accepted arrest, not even allowing Peter to defend him — let alone calling on God to “send me more than twelve legions of angels.” How humiliated he must have been to see his fondest dream turn to terrifying nightmare, as Jesus was indeed named “King of the Jews”… so said the sign just above a thorn-crowned head gasping for breath.

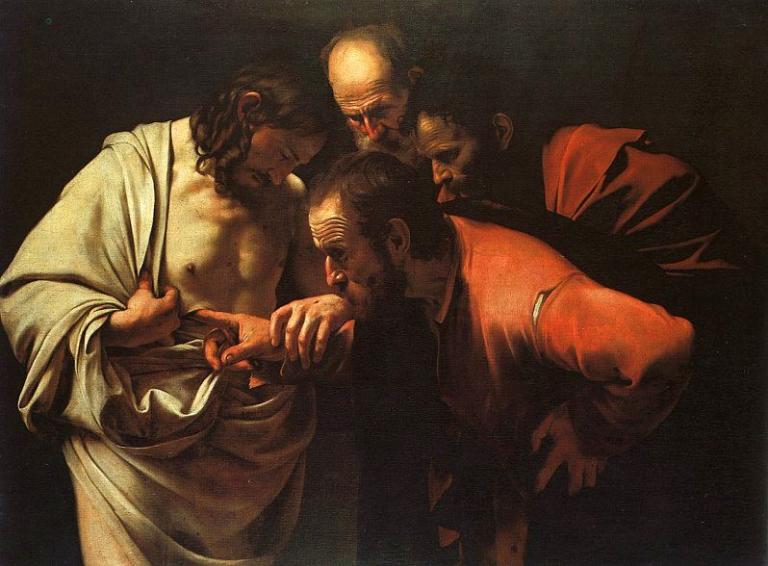

And what of Thomas, who had so recently urged the other disciples to follow Jesus wherever he would take them: “Let us also go, that we may die with him.” But once Jesus neared his true destination, it became clear that Thomas was in the dark: “Lord, we do not know where you are going. How can we know the way?” Did the “inconsiderate zeal” that John Calvin attributed to Thomas evaporate as the way of Jesus led to the truth that his life would end on a cross? Like all the others, Thomas deserted Jesus at his arrest. He may have witnessed the Crucifixion, but apparently he was frightened or disillusioned enough to split off from the company of disciples — when the risen Jesus appeared before them, Thomas was not there.

Wherever he was that day after the Crucifixion, I imagine Thomas entertaining the same doubts as Simon, Peter, and everyone else who had followed a man they knew to be moldering in a tomb.

But I also imagine at least one man in Jerusalem spending that day not tortured by doubt, but reassured that the world was exactly as he knew it to be: Pontius Pilate.

Surely he wasn’t thrilled to start yet another day languishing in a colonial backwater, but at least relations with Herod had taken a turn for the better. At least the local religious lunatics didn’t wake him up to deal with yet another troublemaker speaking pious gibberish. He could forget that his encounter with that carpenter’s son — What was his name again? Jesus, but which one: Jesus Barabbas, or the other? — had left him “greatly amazed,” as his interrogation turned upside-down and he found himself being questioned by someone who didn’t behave remotely like any other prisoner in his experience.

“What is truth?”, Pilate had asked. Not the laws of the gods, he had seen again, but the laws of indifferent nature, being worked out in all their amoral cruelty on a cross.

For Pilate could tell himself once more that there were no kingdoms but those of this world, and none greater than Rome. Pilate wouldn’t live to read Tacitus, but even if it was true that Roman civilization was a violent usurpation, a desert masquerading as Pax, what of it? Such was the human experience. If Pilate knew his Thucydides, he understood that “the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.”

And if these particular weaklings insisted on spiritualizing the political, well, Pilate knew better. He had “realized that it was out of jealousy that they had handed him over.” The next time the chief priests deluded themselves into thinking they had any kind of power and brought before him another Christos, he would know to substitute more earthly words for their claims of “blasphemy.”

Let the superstitious make an omen out of an earthquake. Pilate was unshaken: the world was as it had been and always would be.

Of course, it wasn’t. But how easy it would be to fall back into that belief today. In a week when schedules are disrupted by time off from work, long journeys, and additional worship, there is little to set apart Holy Saturday. Today tempts us to normalcy, to reassure ourselves that nothing is all that different, that no change threatens to permanently inconvenience our lives.

But if the tomb-opening tremors of Good Friday weren’t enough to shake us out of that delusion, remember that Resurrection also brought an earthquake. May Easter dawn with the realization that Jesus is not who his followers and murderers thought him to be. And so, that the world will never be the same again.

Adapted from previous posts at The Pietist Schoolman.