It’s hard to believe that tomorrow marks a full month since a terrible fire ravaged Paris’ venerable Cathedral of Notre-Dame. I was so grateful that Beth was willing to trade spots with me and write our response to that fire. We needed a medievalist both to explain how “history and faith… intertwine within its stone walls” and to remind us that the destruction and reconstruction of such churches is a common theme in history.

Just ten days after the fire as much as $1 billion had been pledged towards the rebuilding effort. There’s debate about the design of the new Notre-Dame de Paris and whether so much money should be spent on such a project. But there’s no real doubt that Notre-Dame will rise again.

However, that hasn’t always been true of older churches that are abruptly, tragically destroyed.

I’m no medievalist, but I do study the two world wars, which were fought in such a way that cathedrals and other churches often suffered significant damage. And it wasn’t always assumed that they would be resurrected. Indeed, people sometimes argued that the ruins would be more meaningful than any reconstruction.

Article 27 of the Hague Convention of 1907 had repeated virtually word for word what its 1899 predecessor had first stated:

In sieges and bombardments all necessary steps must be taken to spare, as far as possible, buildings dedicated to religion, art, science, or charitable purposes, historic monuments … provided they are not being used at the time for military purposes.

But in the war that ravaged Europe in 1914-1918, “buildings dedicated to religion” were rarely spared.

Probably the most famous case involved another cathedral dedicated to “Our Lady” — that of Reims. The cathedral that stood in 1914 had been a Gothic replacement for a Carolingian church that burned in 1210. As late as Charles X in 1825, French monarchs had been crowned in Reims.

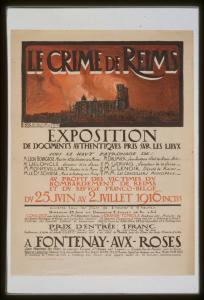

“Despite the hotly contested separation of church and state in 1905,” points out art historian Thomas Gaehtgens, “this cathedral remained a place for both religious and patriotic reflection. Even France’s bitterest enemy ought to have done everything possible to avoid shelling such a powerfully symbolic monument.” Yet the German Army shelled it in mid-September 1914, burning the timbers of the roof and causing the lead to melt. “No one doubted the cruelty of war,” Gaehtgens continues, “but to shell a church—and especially Reims Cathedral—was unthinkable, except as an inhuman crime outside the bounds of civilized behavior.”

“Despite the hotly contested separation of church and state in 1905,” points out art historian Thomas Gaehtgens, “this cathedral remained a place for both religious and patriotic reflection. Even France’s bitterest enemy ought to have done everything possible to avoid shelling such a powerfully symbolic monument.” Yet the German Army shelled it in mid-September 1914, burning the timbers of the roof and causing the lead to melt. “No one doubted the cruelty of war,” Gaehtgens continues, “but to shell a church—and especially Reims Cathedral—was unthinkable, except as an inhuman crime outside the bounds of civilized behavior.”

The Germans protested that Allied churches were “being used at the time for military purposes” — i.e., in violation of the Hague Convention. The German general staff issued a report alleging that the French military used the cathedral as an observation post. Even someone as enamored of French culture as art critic Julius Meier-Graefe complained that “the French are very clever to include Reims Cathedral in their front line and lard Antwerp Cathedral with guns. We have to fire at them and then we’re the monsters.”

Whether that’s true or not, firing on cathedrals and other churches did help cast the Germans as monsters in Allied (and then-neutral American) public opinion. Though Reims itself was virtually depopulated, shells continued to crash into its cathedral, so that it “loomed above the town with heavily damaged vaulting and a missing roof, presiding over a terrible landscape of ruins.” (Paris’ Notre Dame survived more or less intact, but it did suffer damage. Two pilots bombed it during an early raid on Paris, an act that “doesn’t exactly improve international opinion of us,” the editor of a Berlin daily noted in his diary.) Throughout Belgium and northern France, ruined churches served as monumental propaganda for the Allies.

There was little doubt that Reims’ cathedral would be rebuilt, but it took years to raise the funds, since the city struggled simply to rebuild housing for returning residents. The same month that Germany signed the Treaty of Versailles, the New York Times reported that the “wreck of the martyred city lies as the war left it. The stark skeleton of its noble cathedral raises its tortured towers in eloquent agony.”

Finally, major gifts from John D. Rockefeller in 1924 and 1927 helped speed reconstruction. The full reopening took place in July 1938 — just over a year before a new war — with far more destructive aerial bombing than the 1914 raid that dented Notre-Dame de Paris — would destroy even more churches.

Most of those were soon rebuilt, with the notable exception of Dresden’s Frauenkirche — demolished in the infamous Allied bombing of February 1945, during which incendiary bombs raised the temperature inside the church to over 1,000°C. But Soviet occupiers and then the East German government had no interest in restoring the church and instead designated the ruins as an anti-war memorial.

The Frauenkirche wasn’t rebuilt until the 60th anniversary of the bombing, and then only after critics argued that the €180 million could have been better spent. “Did eastern Germany not need roads, roofs and factories more than an expensive church?”, the German president asked at the reconsecration ceremony. “But a group of residents said Dresden needed more. And now we can see that those people were right.” The city’s Protestant bishop agreed: “A deep wound that has bled for so long can be healed. From hate and evil a community of reconciliation can grow, which makes peace possible.”

Still, the idea of leaving a ruined church as a kind of ugly memorial is not merely Communist propaganda, nor was it original to the post-WWII era.

Few cities suffered as much damage during WWI as did Ieper (Ypres), Belgium, which hosted three major battles between 1914 and 1918. King George V hoped that the British government would simply buy the city and leave all of it untouched as “holy ground.” (One backer of this plan was Winston Churchill, who had fought outside in Ypres in 1916 and argued that “A more sacred place for the British race does not exist in the world.”) Other British notables proposed leaving the city’s center unreconstructed as a memorial to the tens of thousands of Commonwealth soldiers who passed through it en route to their deaths. This so-called “zone of silence” would have included the ruins of St. Martin’s Church (a cathedral until the Napoleonic era).

In the end, the British instead commissioned Sir Reginald Blomfield to construct the monumental Menin Gate memorial at one of the historic entrances to the medieval city. A few blocks away, St. Martin’s was rebuilt between 1922 and 1930, as nearly an exact replica of the pre-war church — save for a slightly taller spire.

But I’ve been to at least one unrestored church ruin from 1914-1918. Just down the hill from the largest French military cemetery of the war (named for its memorial basilica, Notre Dame de Lorette) and the new Ring of Remembrance (engraved with almost 600,000 names) sits the commune of Ablain-Saint-Nazaire (pop. 1,784). Its “Old Church” dates back to the 16th century, was ruined early on in World War I, and has remained in that state ever since, as this Atlas Obscura article explains:

Rather than rebuild the structure, local officials opted to keep it in its ruined state as a testimony to the casualties of war (though a lack of funding may have also influenced their decision). While a new church was being built, the villagers held their services in a hut donated by the Canadians.

Now, it’s a quiet spot near one of France’s largest military cemeteries. The contrast between the maintained lawn and crumbling ruins is sharp. The shell holes and graffiti carved by German, Canadian, British, and French soldiers make it possible to read the history written on the church’s stones. People can wander around the roofless ruins, and even picnic on the grounds on the rare days when the northern French sun dares to show its face.