It was a lovely evening in Bayeux this past June, and my parents and I had found a quiet bistro serving “authentic Norman” food. Acting braver than I felt, I decided to start with the “sailor’s platter”: shrimp, snails, and oysters. As soon as our appetizers arrived, I did what any self-respecting citizen of the digital age does: took out my iPhone and snapped a picture.

I don’t actually memorialize my food all that often — mostly on trips to Europe, primarily to make my wife jealous that she’s not there eating with me, and almost never for wider dissemination. For example, I’ve only ever shared one such photo on Instagram. (And it took no courage whatsoever to eat Kaiserschmarrn!)

https://www.instagram.com/p/Bs2pAKenbIv/

But if critic Theodore Gioia is right, not only has “photographing food has evolved from a niche hobby into a generational habit,” but sharing those images on social media “has elevated our diet choices from private quirks into a cornerstone of public identity.” Writing earlier this month for The American Scholar, Gioia admitted that it would be easy “dismiss these photos as brazen self-promotion or a symptom of millennial self-absorption… Slurs such as ‘foodgasm’ and ‘food porn’ often taint these photos with the suggestion of lechery.”

But he thought there was a more sincere, even ancient impulse behind food Instagram:

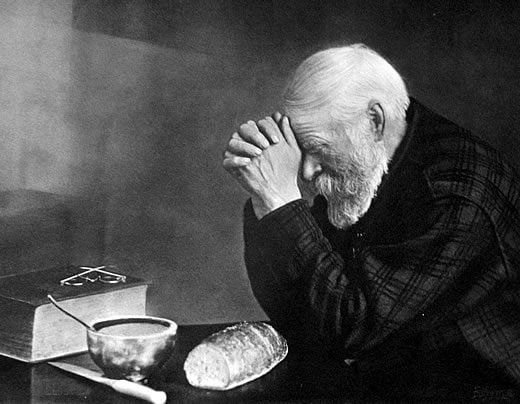

As odd as it sounds, I do not see pornography in these images. I find prayer.

I believe these pictures are a new incarnation of an ancient instinct: the ritual of tableside grace. Derived from the Latin gratia for “thanks,” grace is a specific type of prayer given before or after a meal to express gratitude and to invoke a blessing. It is an exercise in devoting reverential attention to life’s bounty, and through this enriched attention, achieving an expanded sense of belonging. “It becomes believers not to take food … before interposing a prayer,” Tertullian wrote in the third century, “for the refreshments and nourishments of the spirit are to be held prior to those of the flesh, and things heavenly prior to things earthly.” Grace is more than gratitude—it is gratitude ascendant, aimed above the earthly appetite toward a higher vocation. The Catholic Catechism defines prayer as “the raising of one’s mind and heart to God.” Thus grace gives our gratitude wings that lift the mind from the necessities of the flesh toward the nourishments of the spirit. For many people, photographing their entrées fills the same social role as grace: a ritual of aspirational attention that elevates bodily sustenance into spiritual refreshment through the simple power of a genuine “thank you.”

“Once we sent our prayers to heaven,” Gioia concluded — recalling his Catholic family’s habit of reciting “Bless us, O Lord, and these Thy gifts” at the dinner table. “Now we send them to Instagram.”

As it happens, one of the most widely read posts in my Anxious Bench archive is a short history of one such Christian table grace, a prayer particularly popular with the pietistic Protestants of my ancestry:

Come, Lord Jesus, be our guest,

And let these gifts to us be blessed.

Amen.

After reading Gioia’s thought-provoking piece, I went back through that post… and came away thinking that he had missed the point about table graces.

First, while Gioia finds Instagram “uniquely equipped to realize prayer’s promise of transcendent connection, offering a link not with some distant unknowable Infinite Being but a responsive community of vocal supporters,” he fails to see that a mealtime prayer is about transcendent and immanent connection. He might see its divine recipient as distant and unknowable, but “Come Lord, Jesus” is offered to the Word made flesh who has come directly into our midst: “the living bread,” whose Body is eaten in another prayer-prefaced meal. (“Be present at our table, Lord” is the inviting first line of our family’s other, sung grace.) That kind of prayer, I wrote, “reminds us that Christian faith is not purely intellectual or other-worldly; it is incarnate, inseparable from the body’s physical needs.”

Second, while Gioia is right to associate such prayers — ancient or hyper-modern — with communal connection, there’s a significant difference between the anonymous crowd liking a photo on Instagram and the Christian community that shares a table grace.

Instagram, Gioia explains aptly, “unites a visual medium of presentation with a mass dissemination technology which instantly transmits images to the screens of a billion people worldwide. Unlike Facebook users, Instagrammers don’t have ‘friends’—they have ‘followers.’ This is the technology of evangelism.” Moreover, Instagram “has become a hothouse for burgeoning systems of food beliefs—even what one might call food theologies.”

But even if you buy his argument that Instagram thereby helps its millennial users reroute “the redemptive impulse… from Sunday sermons to dieting credos,” his mixing of religious metaphors obscures something distinctive about table grace that can’t possibly translate to the experience of social media:

I don’t say “Come, Lord Jesus” for followers, but with family and friends. And only a small number of them.

A table grace isn’t offered in response to an altar call at an evangelistic crusade, or as part of a liturgy shared with hundreds in a sanctuary and echoing millions more around the world. Meaningful as those prayers are, “Come, Lord Jesus” is the most intimate prayer I pray. Just thinking of it brings to mind those I love most in the world: their voices in parallel to mine; the reassuring feel of their hands on mine; the love we share for the one who came to us — comes to us again and again — in love.

It may seem ironic to throw this idea into the ether of the blogosphere. (And yeah, I’ll share it via Twitter and Facebook, though probably not Instagram.) But as much as any other Christian practice, table grace reminds me that there are limits to digital community.