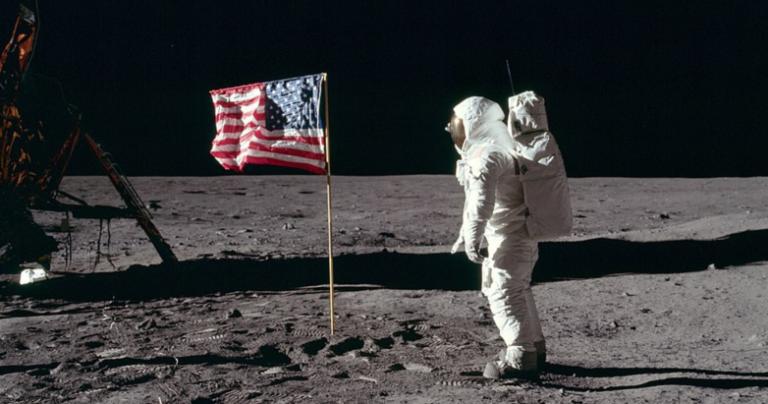

Fifty years ago today, a Saturn V rocket blasted off from the Kennedy Space Center, carrying Apollo 11 on the first leg of its historic journey to the surface of the moon. I’ll be interested to see how people interpret that anniversary this week. But as I’ve glanced back at the history of the Space Race, I’m struck again at how contemporaries attached religious — or at least metaphysical or moral — meaning to Apollo 11 and its predecessors.

I wrote two posts on the religious history of NASA last year: the first drawing heavily on Kendrick Oliver’s To Touch the Face of God, then a second on the “spiritual, but not religious” life of Neil Armstrong. Today I just want to offer a few more examples of the intersection of religion with the Space Race: one from my ongoing research project, and the others sparked by watching the new PBS documentary, Chasing the Moon.

Directed by Robert Stone (son of British historian Lawrence Stone), the three-part American Experience film opens on July 16, 1969, with observers weighing in on Apollo 11 as it prepares to take off. Oddly enough, one of the most profoundly religious takes comes from the sportswriter Heywood Hale Broun, commenting for CBS from his vantage point several miles away on Cocoa Beach:

Some of us think that the tremendous interest in space travel is, in a sense, a search for another Eden – that man has a kind of guilt about the world in which he lives and that he has despoiled the place where he is, and that perhaps he ought now in his maturity to set out to find another place, a place which man could go to, leaving behind the rusty cage in which his own mistakes have held him.

It wasn’t the first time in the Space Race that someone had reached back to the beginning of the Bible to make meaning of the quest for the moon. The previous Christmas Eve, the three astronauts on Apollo 8 had read the King James version of Genesis 1:1-10 as they orbited the moon. Breaking into tears as he listened, Apollo flight director Gene Kranz said that he “felt the presence of creation and the Creator.”

It’s only a small step, not a giant leap, from that sentiment to feeling that going to the moon’s surface would help to retrieve the innocence of Eden from the “rusty cage” of the Fall.

But one crew member on Apollo 8 insists in Chasing the Moon that the Genesis reading “was not a religious thing, so much as it was a kind of a hard hit to the psychological solar plexus, that would help mark, to humankind the gravity – so to speak – of man’s first departure from his home planet.” That’s the voice of Bill Anders, who, Oliver notes, “maintained a public silence about the dwindling of his own personal faith” after returning to Earth. Raised a Catholic, Anders told Stone that:

All religions are based on the fact that the Earth is the focus of the universe, and God sits up there with his super computer and keeps track of all the rights and wrongs. Orbiting Earth, and then going to the Moon – it’s given me a different outlook. The Earth is really nowhere near as special as we’d like to think it is. Though it is our home planet for humans, and it’s the only one we’ve got right now and there’s none in easy sight to get to, so therefore we ought to take care of it. But, we shouldn’t think that this is the designated center of everything.

While Anders’ version of the theme is distinctly non-religious, his comment does help illustrate how the Space Race de-centered Earth and shifted human perspectives to whatever populated “the heavens.”As David Noble put it in his book on religion and technology, “the enchantment of spaceflight was fundamentally tied to the other-worldly prospect of heavenly ascent.” I don’t think it’s in Chasing the Moon, but Broun described his fellow onlookers on July 16, 1969 as “just staring and reaching” while they watched Apollo 11 climb higher and higher: “It was the poetry of hope, if you will, unspoken but seen in the kind of concentrated gestures that people had as they reached up and up with the rocket.”

But Noble worried that looking to the heavens kept Americans’ eyes off more pressing problems on terra firma. (“We ought to take care of it,” Anders allowed.) In the documentary’s introduction, Broun may have been thinking about a new Eden, but Ralph Abernathy tried to keep the focus on the “rusty cage” of American society.

Joined by hundreds of other members of the Poor People’s Campaign, the Christian minister and civil rights activist had come to Cape Kennedy a day before the launch to protest. “We may go on from this day to Mars and to Jupiter and even to the heavens beyond,” Abernathy preached, “but as long as racism, poverty, hunger, and war prevail on the Earth, we as a civilized nation have failed.”

Abernathy was then the head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, taking up that mantle from Martin Luther King, Jr. Exactly one year before he was assassinated in Memphis, King had been in San Francisco, where he too complained about the misplaced priorities of the Cold War and Space Race:

If we can spend 35 billion dollars a year to fight an ill considered war in Vietnam and 20 billion dollars to put a man on the moon, our nation can spend billions of dollars to put God’s children on their own two feet, right here on Earth.

But even Abernathy admitted that he “succumbed to the awe-inspiring launch.” As James Hansen noted in the prologue to his biography of Neil Armstrong, the head of SCLC ultimately felt like “one of the proudest Americans as I stood on this soil. I think it’s really holy ground.”

And at least twice, Chasing the Moon hints at how civil religion and American exceptionalism were fused in the Space Race. In the 1950 science fiction film Destination Moon, the first words of an American on the lunar surface are quite different from Neil Armstrong’s: “By the grace of God, in the name of the United States of America, I take possession of this planet on behalf of, and for the benefit of, all mankind.” Chasing the Moon presents that clip as an example of the influence of the rocket scientist Wernher von Braun, who consulted frequently with filmmakers in the 1950s after having decided to transfer his loyalties from Nazi Germany to Cold War America because he wanted to give rockets “to a nation whose leaders… were governed not by the laws of materialism but by the laws of Christianity and humanity.”

(One of the most vocal Christians in the space program, Von Braun had an evangelical conversion experience not long after coming to the United States. For a sample of how his faith was presented publicly, see pp. 26-27 of this 1966 issue of the Assemblies of God magazine, The Pentecostal Evangel, about revivalist C.M. Ward’s interview with Von Braun. Earlier in the same issue, a Texas pastor claims that he “discovered God in the manned spacecraft center” in Houston… because he ended up talking to Neil Armstrong’s rather devout mother.)

One of the men who had originally inspired Von Braun to pursue space exploration was my current research subject, Charles Lindbergh, who offered his own interpretation of the Space Race in the July 4, 1969 issue of Life magazine.

Both as a legendary pilot and an early champion of the pioneering work of rocket scientist Robert Goddard, Lindbergh had been a kind of grandfather to the Apollo program. Initially, he had declined publisher Ralph Graves’ invitation to write about Apollo, on the grounds that he had ceased to write about aviation. But the reclusive aviator did let Graves publish his reflections on the “motivations behind man’s great adventures.”

After recounting some of his own career, Lindbergh recalled being present at the launch of Apollo 8, which left him

literally hypnotized… Here, after epoch-measured trials of evolution, earth’s life was voyaging to another celestial body. Here one saw our civilization flowering toward the stars. Here modern man had been rewarded for his confidence in science and technology. Soon he would be orbiting the moon.

But in the end, Lindbergh professed himself less interested in technological progress or national triumph. Instead, he now saw

scientific accomplishment as a path, not an end; a path leading to and disappearing in mystery. Science, in fact, forms many paths branching from the trunk of human progress; and on every periphery they end in the miraculous. Following these paths far enough, and long enough, one must eventually conclude that science itself is a miracle—like the awareness of man arising from and then disappearing into the nothingness of space. Rather than nullifying religion and proving that “God is dead,” science enhances spiritual values by revealing the magnitudes and minitudes—from cosmos to atom—through which man extends and of which he is composed.

As Apollo 11 prepared to travel to the moon, Lindbergh concluded that the giant leap for mankind was not to reach beyond Earth but within ourselves, to better understand “the infinite and infinitely evolving qualities that have resulted in the awareness, shape and character of man…. Through his evolving awareness, and his awareness of that awareness, he can merge with the miraculous—to which we can attach what better name than ‘God’?”