Several years ago, I wrote a post about the way that early modern Christians understood pelicans as a symbol of God’s mercy. I’m reposting my original piece below, drawing from the Anxious Bench archives.

I’ve been reflecting on the piece recently. Two weeks ago, I wrote about the symbol of the rooster in early Christianity. And I noticed that my fellow blogger Chris Gehrz remembered my post when watching a documentary this past spring. Perhaps a reminder that Christians sometimes try too hard to see the gospel in nature!

https://twitter.com/cgehrz/status/1142595740021272576?s=20

Here’s the original post:

Whenever I’m in Salt Lake City, I like to stop at the Cathedral of the Madeleine.

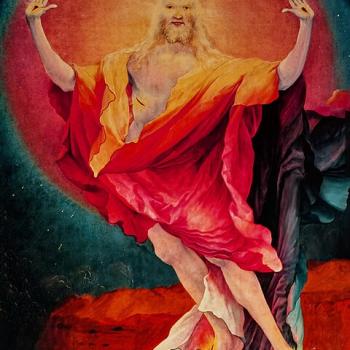

While at the cathedral last week, I noticed something that will no doubt be common knowledge to students of medieval Christianity but was new to me. In two paintings — on the central mural behind the altar and in one of the stations of the cross — is an image of a pelican with her young chicks. A pamphlet informs that the image symbolizes “Christ’s sacrifice based on a belief in the Middle Ages that the pelican feeds its young with its own blood.”

It took but a few minutes of googling to realize that this belief dates to the earliest centuries of Christianity. The Physiologos (author unknown, and without a full English translation as best I can tell) dates most likely to the third or fourth century. Its descriptions of the natural world and its creatures served as the basis for several medieval illustrated manuscripts and beastiaries. According to William Saunders, the Physiologos says this about the Pelican:

The little pelicans strike their parents, and the parents, striking back, kill them. But on the third day the mother pelican strikes and opens her side and pours blood over her dead young. In this way they are revivified and made well. So Our Lord Jesus Christ says also through the prophet Isaiah: I have brought up children and exalted them, but they have despised me (Is 1:2). We struck God by serving the creature rather than the Creator. Therefore He deigned to ascend the cross, and when His side was pierced, blood and water gushed forth unto our salvation and eternal life.

From this and other sources, the identification of the Pelican as a natural type of Christ became pervasive among European Christians. Dante, Shakespeare, and a host of poets and artists utilized the trope.

Some medieval beastiaries, such as the 13th century Aberdeen Beastiary and Harley Beastiary, depict the mother both killing and reviving her chicks.

Here is the description of the pelican from the Aberdeen Beastiary:

It is devoted to its young. When it gives birth and the young begin to grow, they strike their parents in the face. But their parents, striking back, kill them. On the third day, however, the mother-bird, with a blow to her flank, opens up her side and lies on her young and lets her blood pour over the bodies of the dead, and so raises them from the dead.

In a mystic sense, the pelican signifies Christ; Egypt, the world. The pelican lives in solitude, as Christ alone condescended to be born of a virgin without intercourse with a man. It is solitary, because it is free from sin, as also is the life of Christ. It kills its young with its beak as preaching the word of God converts the unbelievers. It weeps ceaselessly for its young, as Christ wept with pity when he raised Lazarus. Thus after three days, it revives its young with its blood, as Christ saves us, whom he has redeemed with his own blood.

…The pelican kills its young with its beak because the righteous man considers and rejects his sinful thoughts and deeds out of his own mouth, saying: ‘I said, I will confess my transgressions unto the Lord, and thou forgavest the iniquity of my sin’ (Psalms, 32:5). It weeps for its young for three days: this teaches us that whatever we have done wrong by thought, word or deed, is expunged by tears. It revives its young by sprinkling them with its blood, as when we concern ourselves less with matters of flesh and blood and concentrate on spiritual acts, by conducting ourselves virtuously.

It is a rich description of human rebellion, divine wrath, and self-emptying atonement.

The image also found its way into literature ranging from prayers to plays. Thomas Aquinas, in a Eucharistic poem later used as a hymn, wrote this verse (in Edward Bouvier Pusey’s translation):

Pelican of mercy, Jesus, Lord and God,

Cleanse me, wretched sinner, in Thy Precious Blood:

Blood where one drop for human-kind outpoured

Might from all transgression have the world restored.

It’s a strikingly feminine image of the Son of God, who longed to gather his children as a hen shelters her chicks under her wing.

Many centuries later, the trope appears in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, in which Laertes promises the king: To his good friend thus wide, Ill ope my arms / And, like the kind, life-rendering pelican / Repast them with my blood

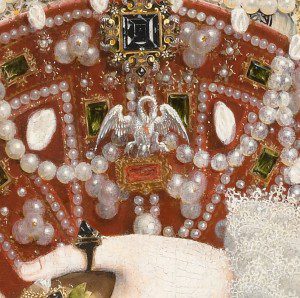

Queen Elizabeth I used the pelican motif to portray herself as the mother of the Church of England, as depicted in a painting by Nicholas Hilliard.

The panther, the phoenix, and other creatures (but not the beaver) were also allegories of Christ.

Though they are indisputably majestic and fascinating birds, pelicans do not actually feed or revive their chicks with their own blood, and beavers do not chew off their own testicles to save themselves from hunters who desired those organs for medicinal purposes.

Still, I marvel at the way that earlier Christians interpreted the world around them. When they looked at the natural world, early and medieval Christians saw more than brilliant and awe-inspiring evidences of divinity. They drew specific theological lessons from the birds and beasts they encountered, lessons that European Christians preserved and passed down for centuries. Those who have eyes to see, let them see.

Note: The Medieval Beastiary is chock-full of information, images, and links pertaining to the above subject.