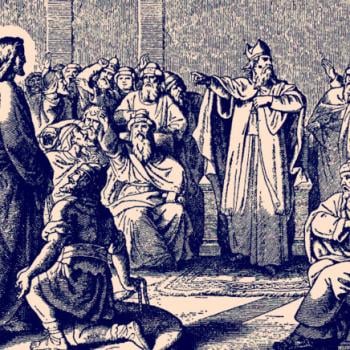

In 1602, the Italian painter Caravaggio completed one of the most moving paintings of the early Baroque period, The Incredulity of Saint Thomas. The subject matter was common enough. The image depicts the apostle Thomas meeting the risen Christ in John’s Gospel. Thomas, upon hearing the news that Christ had risen from the dead, fearing it too good to be true. “Unless I see the mark of the nails in his hands,” Thomas said, “and put my finger in his side, I will not believe.” When Christ appeared to Thomas, he bid the skeptical apostle, “Reach out your hand and put it in my side. Do not doubt but believe.” While the subject was well-known, Caravaggio’s method marks the internalization and psychological state of human actors for which the painter would become famous. Caravaggio’s Thomas emphasizes the bewilderment on the face not only of Thomas, but of Peter and John. Their raised brows and wrinkled foreheads capture the inexplicable event of Christ’s miraculous resurrection, while Jesus’s steady hand gently guides Thomas’s finger into the central physical and sacramental locus of Christ’s passion, the laceration of his side by a soldier’s spear. The bleak background and dimly lit subjects are contrasted by deep hues of red in the garments of Thomas and John and the rush of blood to the apostles’ faces as they lean forward in bewilderment.

The appeal to the natural subject, the exploration of human interiority and emotion, the play of light and shadow, and the vibrant colors that illuminated the canvases of baroque painters were framed by larger cultural trends: changing conceptions of reality, on scientific advances, on shifting religious moods. Baroque art also relied on expanding markets and economic changes. According to journalist Devon Van Houten Maldonado, Caravaggio’s Thomas, flushing and clothed in a frayed red tunic, was brought to life using a pigment called cochineal, which emerged onto the European market in the 1500s.

The red dye came from parasitic insects that attached to cacti. The female insect was collected, boiled, dried, and crushed into powder. This was then combined with various materials to produce a wide spectrum of reds. Cochineal’s production began in the colonies of New Spain in the 1520s, when Hernan Cortes saw the pigment being sold in Mexica markets. When report of the dye reached Charles I, the king wrote to Cortes demanding to know how much was available and to “cause as much as possible to be collected with diligence.” According to Elena Phipps, the demand for cochineal red was almost immediate. “By the mid-sixteenth century,” she writes, “the Spanish flotillas that traveled annually between the Americas and Spain were bringing literally tons of the dried insects to Europe.” Cochineal exploded onto the textile scene, becoming the in-demand color for everything from priestly vestments to queens’ dresses to rugs. At its height, cochineal was second only to silver in as the most valuable export of the Spanish colonies in Mexico.

Production of the dye, while not as physically demanding as silver mining, was labor intensive. Carlos Marichal writes that the European demand for the red required the Spanish to incentivize production of cochineal over other crops or commodities. In the early years of a lucrative trade, the region of Tlaxcala emerged as an early center of cochineal production. The Tlaxcalan nobles embraced the Spanish in their war against the Aztec, and were early beneficiaries of Spanish rule as members of the municipal council under a Spanish governor. Yet, the arrival of Spanish Christians and Spanish economic ambitions created new challenges for the Tlaxcalan community. The council’s minutes illustrate the competing interests of Nahua community identity with the new realities of Christianization, Spanish materialism, and colonial subjection.

A meeting in 1553 records the concerns of the council specifically over the expansion of cochineal production in Tlaxcala. According to the deliberation, food was becoming expensive in the city because “everyone does nothing but take care of cochineal cactus.” The cochineal was responsible for “excessive” sin in the community.

These cochineal owners devote themselves to their cochineal on Sundays and holy days; no longer do they go to church to hear mass as the holy church commands us, but look only to getting their sustenance and their cacao, which makes them proud…Not remembering how our lord God mercifully granted them whatever wealth is theirs, they vainly squander it. And he who belonged to someone no longer respects whoever was his lord and master, because he is seen to have gold and cacao.

Lisa Sousa rightly notes the nobles’ anxiety was likely performative, since they too profited from their own cochineal produce. However, the council meeting still illustrates a longstanding issue within the colonial project of Christianization. The Spanish colonial ideal of a colonial subject as a pious Christian is pitted against Spanish ambitions for the colonial subject as producer. Market demands undoubtedly influenced the limits of Christian observance.

Christianity is a tradition of storytelling. In fact, I’d argue stories are the basic units of the Christian religion. Christians are shaped by the stories of Christ, the stories of the saints and martyrs, the stories of our families and friends. We are also shaped by the stories we tell about ourselves. How we tell the story—who we include and exclude, and how we costume the main characters—matters. To me, the account of cochineal as a product of European consumption is a window into how to tell the story of Christianity itself. It encompasses diverse, often competing, but interconnected subplots.

To be sure, I am not telling the full story of Mesoamerican Christians and the production of cochineal. Jeremy Baskes writes at length about indigenous resistance to colonial lending policies and the initiative that many Mesoamerican communities took to subvert the market for their own benefit. My only purpose here is to point to the interdisciplinary and interconnected work of doing Christian history.

There is a connection between the beauty of baroque religious expression and the ugliness of exploitative labor practices and consumerism. The faith of Caravaggio’s Thomas was, in some ways, strengthened at the expense of Nahua laborers’ own faith. Italian Christian devotion was enriched through the exploitation of Mesoamerican Christians. Any story about Christianity that cannot hold together beauty and pain, oppression and resistance, vitality and regression, may be an easier story to tell, but it is little more than fan-fiction.