A blast of arctic air hit much of the United States last week and brought snow, wind, and intense cold to much of the country.

It was so cold that Republican presidential candidates worried that Iowans wouldn’t show up for the Republican caucuses, held on a day when wind chills were 40 degrees below zero. It was so cold that at the NFL playoff game between the Chiefs and the Dolphins—the fourth coldest game in NFL history—the Kansas City Fire Department had to administer aid to dozens of fans, some of whom had frostbite and hypothermia. It was so cold that the temperatures may have been one reason why the helmet of the Chiefs’ quarterback, Patrick Mahomes, broke. (“Extreme conditions like those are bound to test the limits of even the highest-performing products,” the helmet manufacturer said.) And when he reached for his replacement helmet, Mahomes found that it was frozen and didn’t fit on his head.

It was so cold that my daughter, like many other schoolchildren across America, saw the weather report and raised her hopes for the official declaration of the most delightful of winter holidays: the Snow Day.

She got one, but not really. Her school granted her a “Snow Day”—they literally put the term in quotation marks—but it was actually what they termed a “virtual asynchronous day,” meaning she was still required to log into her school’s online system and do an array of assignments: take notes on a video about logarithmic functions, do a precalculus problem set, and complete a biology lab assignment about mitosis.

It was not the surprise day of play associated with Snow Days of yore, a holiday dedicated to building snow forts and drinking hot cocoa and wearing pajamas all day while watching movies under wool blankets. Much to her disappointment, it was simply another day of work, just one that happened to have been at home, rather than at school.

I felt sorry for her, that she was deprived of the opportunity to celebrate a true Snow Day, which is one of my favorite holidays on the winter calendar. In his 2004 essay “Snow Day as Holiday,” the religious studies scholar Joshua Dubler argued that the Snow Day is a civic holiday in the United States. In a country where capitalism is the civil religion, where work time is our church time, and where the daily practice of productivity is the ultimate display of our virtue, the Snow Day is a special day: time stops, expectations for work cease, and we play.

But as my daughter’s experience indicated, the Snow Day is under threat. It is the victim of many forces: the relentless push for greater productivity, imposed even upon schoolchildren; the advent of Zoom and other new technology, which blurs the boundary between school and home; and the warming climate, which has increased temperatures and reduced snowfall. Ultimately, the culprit is capitalism. If capitalism created the conditions for the Snow Day to become a holiday, capitalism has also created the conditions for its demise.

Before I lament the end of the Snow Day, let us first define our terms. What is a Snow Day, and why does it matter? As Dubler explained, a Snow Day is not simply a day characterized by heavy snowfall. As he wrote,

Although indeed frequently accompanied by street-carving plows and consequent roadside bluffs, a Snow Day is a civic rather than natural phenomenon. Necessarily falling during the workweek, a Snow Day is a day in which due to a snowstorm or perhaps merely the erroneous prognostication of one, civic institutions are closed, the activities of the world suspended. Primarily a children’s festival, the principal closing that of the school. Roving the calendar from October to April, the Snow Day issues a temporary stay of mundane duty, trumping work and school with a spontaneous winter carnival. In the time and space conventionally allotted for workaday obligations, children and adults are given license for play (62).

What matters, Dubler argued, is not so much what we do on Snow Days, but what we don’t do—which is work. The Snow Day is welcome by its participants because it offers a respite from the daily expectation of labor and productivity. As Dubler explained,

…[T]he suspension afforded by the Snow Day is less about what it is than what it is not. While the Snow Day does indeed re-enchant space and stages in it a winter carnival featuring creative play and freakish congeniality, it is more importantly a stop-time, a temporary deferral of worldly obligation. Therein, the fetishization of the Snow Day explores the anxiety of compulsive productivity that is among our culture’s governing conditions (62-63).

By stopping time and forcing people to play, Dubler argued, the Snow Day challenges deep-seated aspects of American culture:

For against the march of time and its burdens, the Snow Day is indeed a revolution. Or more accurately, it is precisely the opposite. It is a stop-time. Signaling a temporary suspension of earthly revolution, the Snow Day stops the world so we can get off, even if only for a magical day. Providing a spontaneous and long-overdue fermata in the score of time, the Snow Day forces upon us a break that, time-rationalized as we are, we are unable to afford ourselves. The Snow Day enforces leisure of a non-productive kind. It forces us to sit and drink tea, even on a Monday morning. It is a festival of ultimate freedom: the freedom to do nothing at all, especially on a Monday morning, and most definitely sometime between Monday and Friday. For snow on a Sunday, though a snowy day, is not a Snow Day…It is precisely the smothering of civic institutions, the suppression of capitalism (and the need to capitalize) that makes the festival. And in this sense, in the absence of an autonomous church time distinct from merchant’s time, the Snow Day’s passion for disruption, its hunger to consume both the civic and the economic might mark it as the purest festival that we have (70-71).

According to Dubler, capitalism is an important context that gives the Snow Day meaning in the first place. In the United States, where capitalism is at the core of our nation’s civil religion, the Snow Day is set apart from everyday life because it is a day when we cease all productivity. As Dubler explained,

…[I]t is the marketplace—and the marketplace mentality that we carry with us home, to school and to Church as well—in which resides the elemental tenet truly constitutive to the American Civil Religion. I refer, of course, to Capitalism…To appropriate the bromide of one of our most rarely cited prophets, the laconic Calvin Coolidge, ‘The religion of America is business.’ It is within a Civil Religion imagined in this way that the Snow Day becomes so remarkable. If [Walter] Benjamin is correct (rather than merely hyperbolic) and the Religion of Capitalism has no weekdays only festivals, then the Snow Day—properly observed—might mark the sole exception. And therein its extraordinary pleasure: in a culture in which merchant’s time is church time, the Snow Day represents a rare moment of escape in which one is mandated neither to produce nor consume. As such, the Snow Day is the celebration of the capitalist carnivalesque (74).

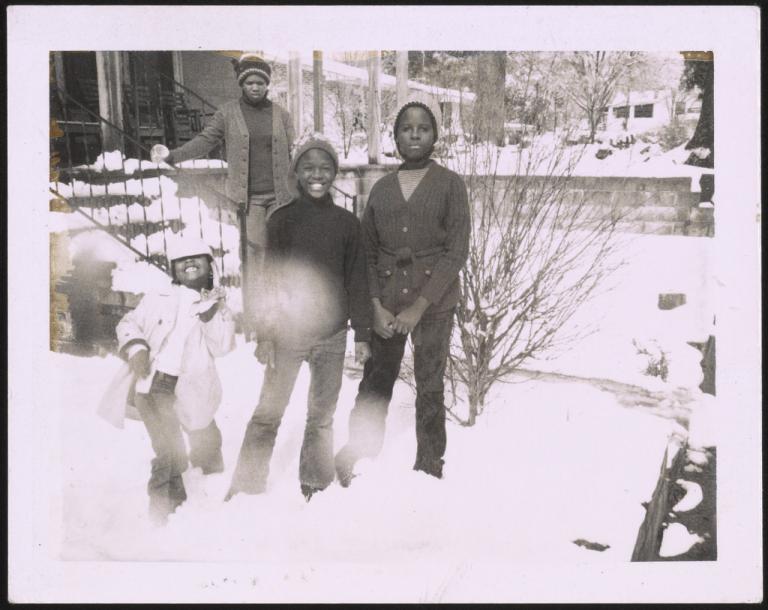

That the Snow Day might be “the purest festival we have” and a “celebration of the capitalist carnivalesque” is reflected in American popular culture. From The Simpsons to children’s literature, the Snow Day—both its familiar rituals and its magical possibilities—is a moment of utter delight. These representations of the Snow Day are not far from reality. Having grown up in snowy mid-Michigan, I recall with great fondness the joys of a Snow Day: the snowball fights and the sledding excursions, the movie marathons with my brother and sister, and, most of all, the relief that I could dodge that math test for just another day. I had license to play, instead of expectations to be productive. In short, I could be a kid.

But as my daughter’s experience last week revealed, the Snow Day as we know it is an endangered holiday. Its demise owes to a number of developments. To begin, there are advancements in technology, especially the internet and the associated tools that make it possible to go to school at home and online: learning management systems, digital textbooks, video conferencing tools, and more. Global events—in particular, the Covid-19 pandemic—facilitated the widespread adoption of this educational technology and acclimated students, teachers, and parents to virtual and hybrid schooling. Their embrace of these changes occurred in part because of the familiar force of capitalism: the continued pressure on students, teachers, and schools to labor, to strive, to be productive, even if people are dying and the world is falling apart.

And while we’re talking about the world falling apart: another reason why the Snow Day as a holiday has an uncertain future is because snow itself has uncertain future. Climate change—the consequence of our capitalist obsession with endless production and consumption, to the detriment of our earth and our atmosphere—means we have warmer weather and less snow. According to climate scientists, global snowfall has decreased 2.7% in the past 50 years, and the Environmental Protection Agency reports that in the United States, total snowfall has decreased in most parts of the country since scientists first started to track these numbers in 1930. Due to a warming climate, precipitation is falling as rain, rather than as snow.

Ultimately, capitalism made the Snow Day the holiday that we love. Capitalism might also take the Snow Day away from us.

I teach at the University of Michigan, where from October through April, snow is a fact of life but where Snow Days are relatively rare because the students here are the ultimate strivers, forever working to be a victor.

And yet last week, as I considered my daughter and her longing for a true Snow Day, I thought that I might set aside ambition for the day and instead bring some spontaneous delight to my students. In an act of both rebellion but mostly nostalgia, I dismissed my students two hours early. I encouraged them to sled, ski, and sleep. I urged them to play and, just for an afternoon, to resist the pressure to be productive. I declared a Snow Day, a holiday that is precious and increasingly rare. I did so in part for my own delight because I don’t know how much longer I’ll have the pleasure of seeing the joy in my students’ eyes when they hear the words: It’s a Snow Day.