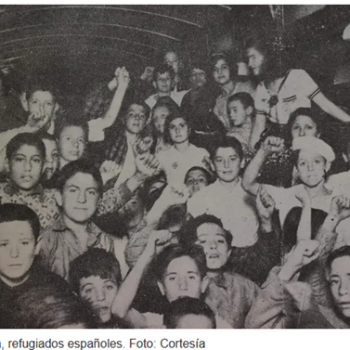

In the past two years, the Trump administration has pushed aggressively for restrictive refugee policies. At present, the number of refugees admitted for resettlement in the United States is at a historic low—capped at 30,000, which is 70% less than during the Obama administration. That number could soon be even lower. Earlier this month, the New York Times reported that the Trump administration is considering a proposal that would “reduce refugee admissions to zero.”

The Trump administration’s assault on the refugee resettlement program has been the target of criticism not only from former military officials and humanitarian organizations, but also religious groups. Having been deeply involved in implementing the federal resettlement program for decades, religious groups have spoken out forcefully against the drastic cuts to the U.S. refugee program. Jenny Yang of the evangelical agency World Relief described the reduction of refugee admissions as a “complete failure of moral leadership,” and Jen Smyers of Church World Service urged the Trump administration to reflect on the fundamental teachings of their religious faith. “I think we would appeal to the president, the vice president and really everyone in the administration who professes to be a person of faith to look at the consequences that this would have and to really go back to basics in terms of the commandment to welcome the stranger,” she said.

American refugee policy is typically analyzed in light of foreign policy commitments, national security concerns, and domestic politics, but it is just as important to understand the religious dimensions of refugee resettlement. Why are religious groups across the denominational and theological spectrum so committed to aiding and advocating for refugees? In what ways is Americans’ involvement in refugee resettlement an expression of religious faith? And how is religion important to refugees as they rebuild their lives in a new country?

To explore these questions, I spoke with Katherine Clifton of the Religion and Resettlement Project, a joint initiative by Princeton University’s Office of Religious Life and The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Migration and Refugee Services. (Full disclosure: I serve as a senior advisor for this project.) This three-year national program, funded by a grant from the Henry Luce Foundation, investigates an underappreciated aspect of refugee resettlement: the fact that religion often plays a critical role in how Americans embrace refugees and, in turn, how refugees embrace America.

“The role of religion in domestic refugee integration, particularly in the US government-sponsored resettlement program, is important, complex, far-reaching, and understudied”

MB: Tell me about the Religion and Resettlement Project—how it developed, what its aims are, and what work you’ve done so far.

KC: In the spring of 2017, Princeton University’s Office of Religious Life’s convened a conference called Seeking Refuge: Faith-Based Approaches to Forced Migration co-sponsored with the Community of Sant’Egidio and, in the fall of 2017, an interfaith policy forum considering refugee integration and religious life co-chaired by the US Conference of Catholic Bishops and the International Rescue Committee. These initiatives sparked the Religion and Resettlement Project (RRP), a three-year national level program launched in October 2018 largely funded by the Luce Foundation that aims to create a better understanding and response to the role that religion plays in the lives of refugees as they resettle in the United States. The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Department of Migration and Refugee Services has been working closely with our office in the development and implementation of this project.

The role of religion in domestic refugee integration, particularly in the US government-sponsored resettlement program, is important, complex, far-reaching, and understudied. Resettled refugees represent the plurality of the world’s religions and roughly 70% are resettled by faith-based organizations, yet there have been no systematic studies or trainings to address the interplay of religion and resettlement. RRP is designed to respond to this gap in order to strengthen refugee services and the resettlement structure at large and to assemble a wide and supportive network of diverse agencies and stakeholders working on and invested in refugee resettlement.

We organize symposia convening refugees, faith leaders, and resettlement agents to explore the multifaceted ways that religion affects displacement, resettlement, and integration in the United States. These symposia offer an opportunity to share case studies, best practices, and personal experiences while allowing all to reflect on and reconfigure how they consider the role of religion in refugees’ lives.

We have initiated an oral history archive of resettled refugees in the US whose religious and spiritual lives have been consequential in their journeys and resettlement. We have led trainings in theoretical and practical oral history methods. We seek to gather and share oral histories from refugees, and are committed to collecting stories from, and involving, the full range of religious communities. The oral history project has several aims including preserving histories at a time when numbers of refugees being resettled in the United States are being significantly rolled back and the future of the resettlement program is unclear, enhancing spaces of dialogue, listening, and chaplaincy within communities and along intercultural and interfaith lines, and providing an opportunity for further civic participation with and for refugees.

We coordinate a robust summer internship program placing 12-15 undergraduate students at resettlement-related NGOs throughout the US for eight weeks. These students spend roughly 20% of their time interviewing resettled refugees for our oral history project by. Beyond the invaluable transfer of stories and wisdom that oral histories produce, the student interviewers learn about the history and development of the resettlement system through intimate firsthand accounts and the civic and moral significance of religion in their lives.

“Faith is something they can take with them”

MB: What are the most important things that your team has learned through the oral history interviews that you’ve done so far?

KC: Unlike almost all of their belongings, faith is something they can take with them. They don’t have to leave it behind and it cannot be taken from them, although the way it manifests itself in their lives often changes as a consequence of their experience. Many narrators have discussed becoming more religious during their resettlement experience. They describe leaving a country where religion is public and inextricable from culture and arriving in the US which holds dear the establishment clause. They decide to be religious in the US to connect them to what they were forced to leave behind. As one intern noted, “Every refugee I’ve spoken to in my interviews has credited their faith as their sole motivator and helper in staying strong.” Others become disillusioned by their faith, particularly in cases of religious persecution, and convert to a different religion or to atheism.

Frequently we hear narratives that emphasize overwhelming positivity about being resettled in the US accompanied by immense gratitude to their faith for sustaining them through hardships both in displacement and during resettlement and integration.

Through these oral histories, the students and I have been reminded how important it is to hold peoples’ stories carefully, to appreciate the great privilege of being entrusted with someone’s intimate life history, to be open and receptive to surprises, and to never define a narrator in terms of tragic events but acknowledge and validate their resilience, creativity, hard work, generosity, and other empowering virtues that they embody. Much of the media continues to use victimizing, pitying language to describe forced migrants and it perpetuates an unfair and untrue power imbalance and (typically white) savior complex. Oral history, on the other hand, offers an opportunity to hear complex stories as a means for creating public narratives around empowerment.

As an ORL, we are especially sensitive to religious traditions and aim to instill this in our student oral historians. One of our student oral historians shared that the oral history project has taught her how “working to help people can never be isolated from sitting down and listening to their stories.” Had she not spoken with refugees as well as taken the time to learn about their histories, cultures, and struggles, “I would not have been able to figure out how best to help them…it reminds me to never forget that civic service is about people and people first.” Just as welcoming newcomers has the potential to empower all involved, oral history has enormous potential to develop our capacity to listen to, empathize with, and understand each other.

“Their faith community taught them, either explicitly or through example, how to be a citizen and develop their civic virtues”

MB: How has this project illuminated how different religious communities have been engaged in immigration and refugee issues?

KC: Resettlement agencies support resettled refugees for the first 90 days of their arrival, but unsurprisingly most refugees take longer than 90 days to become self-sufficient. Nearly every refugee narrator I’ve interviewed mentioned a faith community providing some form of service to them during and after those 90 days, and usually one representing a different faith than theirs. From teaching English to helping to fill out job applications to providing rides to visa hearings or doctor’s appointments, faith-based organizations regularly fill in the government-sponsored resettlement system’s gaps.

Once they found a community that practiced their faith, refugees would discuss the importance of the ritual of going to the same place at a certain time, the sense of belonging, the feeling of being part of something greater than themselves, and the opportunity to be around people who share their beliefs, speak their language, cook their food, – the list continues. Several of them indicated that their faith community taught them, either explicitly or through example, how to be a citizen and develop their civic virtues. Faith communities, as a critical part of the public sphere, play a huge role in community-building. Building civil society helps foster democracy and develops citizenship. Meeting both practical and spiritual needs, faith communities serve a crucial role in refugees’ resettlement and integration in the US.

Faith communities tend to lead the charge on co-sponsorship (or community sponsorship), and one of our budding research projects is trying to understand how this form of resettlement is mutually beneficial to newcomers and faith communities, how it has evolved with and because of faith communities, how welcoming refugees strengthens civil society, and how interfaith and civil society collaborate through the resettlement program to build democracy. Some of our summer interns interviewed religious co-sponsors these questions to hear about their experiences welcoming newcomers to begin to ask these questions.

“My weapons were always my rosary and my bible”

MB: What is the significance of religion in the lives of the refugees you’ve interviewed?

KC: The range of stories is beautiful and breathtaking. Religion doesn’t only live in a particular person or in a particular place of worship and doesn’t remain fixed, but works and evolves across groups, communities, and institutions. Here are some examples:

A Catholic refugee from Rwanda who now works in faith-based refugee services said, “I didn’t choose to be in the US, but I am grateful to be here. The US saved my life. I give thanks to my parents every day for giving me my faith…My weapons were always my rosary and my bible.” The most difficult part of her displacement was when she was in hiding for nine months and couldn’t attend church services. The first thing she asked for when resettled in Tennessee was to be connected to a church. Members of this congregation gave her a washing machine and drier, helped her husband apply for asylum, funded her children’s education, provided her employment as a translator, signed for her to build her credit rating, and countless other generous gestures that she couldn’t have managed alone and that extend far more than the government-sponsored resettlement system.

A Bahai refugee from Iran fled religious persecution and was resettled in the Midwest. The US Bahai community was crucial for the family’s integration into the US in practical ways such as ESL, acquiring housing, and finding employment, and spiritual ways providing “a great sense of comfort and continuity…As I became involved in the community, my confidence in myself and expressing myself grew.” Still, as a non-white family in the Midwest arriving shortly before 9/11, he said, “people’s conditional compassion was challenging.”

A refugee from Cambodia described his family’s total divergence of religious identities once arriving in the US. Although all of them were born Buddhist, he himself converted to Islam, his mother was baptized in a refugee camp and still practices Christianity, his Aunt has become a devout Jehovah’s Witness, another family member established the first Cambodian Mennonite church in America, and his father became a firm atheist being repulsed by religion after the violence he witnessed firsthand. However, other Cambodian refugees established temples and became ordained monks to help the community heal spiritually and ground themselves civically.