I’m a teacher, not a preacher. But every so often, I get the chance to fill a pulpit. Over the weekend, I preached at First Covenant Church in St. Paul, Minnesota. Here’s the text of that Reformation Sunday sermon, on Psalm 46.

Altogether, Martin Luther’s complete works comprise over 120 volumes. I don’t know how many thousands of German and Latin sentences are in all those books, but none is more enduringly powerful than this:

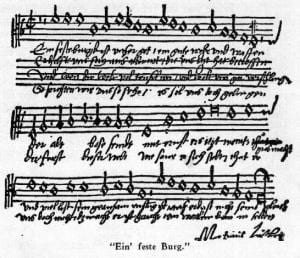

Ein’ feste Burg ist unser Gott, ein’ gute Wehr und Waffen.

It was Luther’s way of paraphrasing the first verse of Psalm 46: “God is our refuge and strength, a very present help in trouble.” And I’m sure that one reason that “A Mighty Fortress” is so powerful is that it reflects Luther’s passion for the psalms. He said later that his love for God “was kindled” by studying those scriptures. As a monk, Luther chanted the entire psalter week after week. As a Bible professor, he began his career with a series of lectures on Psalms; they are the beginning of Luther’s theology. “Everyone,” he wrote, “in whatever situation he may be, finds in it psalms and words that fit his situation… as if they were placed there just for his sake, so that he himself could not put it any better, nor could he find or wish for anything better.”

The psalms, Luther decided, “are not words to hear, but [words] to live.”

So if we hear that God is our refuge and strength, how do we live those words? How do we live into the refuge of God, live out the strength of God?

First, we recognize that we need refuge; we need strength. We hear those words and start to live them by realizing all the ways that the world is a scary place, so tumultuous that even the mountains tremble. We need to take refuge: not in governments or economies — such earthly kingdoms will totter — but in the God of Jacob.

We hear those words and start to live them by accepting that we are not strong enough on our own. One translation of Luther’s hymn puts it this way: “Did we in our own strength confide, our striving would be losing.” When we trust in our own might, we invariably fail — and we tend to damage those around us. So we live this psalm by seeing ourselves with honesty and others with compassion: as people who are wounded and wounding, hurt and hurting, broken and breaking, striving but losing… and yet still bearing the image of the God who loves us through it all.

If we recognize our need for refuge beyond human kingdoms and strength beyond human ability, then we can start to live out the second verse of the psalm: “Therefore, we will not fear, though the earth should change…”

Now, there’s nothing wrong with feeling fear. Another great Protestant reformer, John Calvin, said that the psalmist really meant that we should not have “the sort of bewilderment that the unbelieving have.” Though bombarded with the sights and sounds of foaming waters and shaking mountains, we need not feel confused and overwhelmed. What “we will not fear” means, said Calvin, is that we should “know that in the midst of our fear we will not be oppressed with fear, because we have sheltered ourselves in God and have our refuge in the help he has promised us.”

A few years after he wrote “A Mighty Fortress,” Martin Luther finished translating the Old Testament into German. He started his version of the psalm with this phrase: Gott ist uns’re Zuversicht und Stärke — “God is our confidence and strength.” Hear this as a call to prayer: the more we confide our fears to God, the more confidence we will find in God. But it’s not a passive, cloistered refuge. The root of the German word for confidence is a verb that means, loosely, “give it a try.” If you find refuge in God, you will live boldly, not fearfully.

So why do we find this so hard? Why do Christians remain fearful?

The earth changes, and we let ourselves be oppressed by fear. Governments change, jobs change, demographics change, cultures and technologies and churches and denominations change — and we fear.

I fear.

Is God not my refuge? Is God not my strength?

Is the Lord of Hosts not with us?

Here’s the problem: we misunderstand the nature of God’s refuge and the power of God’s strength. And because we’re trusting in something that’s not God’s refuge or strength, we find ourselves unable to stop fearing.

I fear that it’s partly Martin Luther’s fault.

Remember: it’s not the psalm that calls God a mighty fortress; that’s Luther, in what’s often called “The Battle Hymn of the Reformation.” I still love that song, but it can steer us wrong in some important ways.

A few years before I was born, Concordia Publishing House put out a Luther biography, meant for kids the age of our 4th grader twins. Entitled Martin Luther: Hero of Faith, its cover depicted a rather athletic Luther astride a battle steed, carrying a sword, and wearing partial armor. He’s a medieval knight; just out of frame, a squire carries his war banner. In the background is an imposing medieval castle.

A few years before I was born, Concordia Publishing House put out a Luther biography, meant for kids the age of our 4th grader twins. Entitled Martin Luther: Hero of Faith, its cover depicted a rather athletic Luther astride a battle steed, carrying a sword, and wearing partial armor. He’s a medieval knight; just out of frame, a squire carries his war banner. In the background is an imposing medieval castle.

Now, Martin Luther never fought in a war; in fact, he spent most of his adult life recovering from illnesses. But he did choose military imagery to convey his idea of God’s refuge and strength. He took inspiration from his experience and observation of a violent age.

In 1521, Luther was hauled up before the political and religious leaders of Germany and told that he had one last chance to recant, on pain of physical death and eternal torment. Luther refused. “Here I stand,” he supposedly said. “I can do no other. God help me. Amen.” While he fully expected to die, Luther survived. He disappeared for a year, confined to the safety of ein’ feste Burg: the Wartburg, a castle towering over a thousand feet above the town of Eisenach.

Such fortresses weren’t just tourist destinations; they were bastions against invasion. As Luther wrote his hymn a few years later, Turkish soldiers surrounded the walls of Vienna. Not long before, Rome itself had been sacked by the armies of the same emperor who declared Luther an outlaw in 1521. Thousands of Romans died while the pope and thirteen cardinals found safety in the Sant’Angelo castle.

So it’s no surprise that Luther portrays God as what our translation calls a “bulwark” — a reinforced wall, whose impenetrable stone keeps out a besieging army. In the original German, he calls God ein’ gute Wehr und Waffen — “a good shield and weapon.” (Think World War II movies: the German army was the Wehrmacht and the German air force was the Luftwaffe.)

Luther didn’t mean it literally. How could he? The psalm promises that our Lord of hosts — of “armies” — “makes wars cease… breaks the bow… shatters the spear… burns the shields with fire” (v 9). Luther understood this. Elsewhere, he commented that this very psalm taught that God “maintained peace against all wars and weapons.”

Stirring as it is, Luther’s hymn can lead us to misread Psalm 46. It tempts us to think of God’s refuge and strength in terms of what we might call national defense or homeland security: as if God’s refuge is something we hide behind; as if God’s strength enables us to repel our enemies. If you turn the German word Wehr into a verb, it means that you “defend yourself” or even “put up a fight.” Or if we Wehr setzen, we “take a stand.”

We can do no other, right? God help us!

How often do we spiritual descendants of Luther think that the test of our faith is our readiness to defend ourselves, or our eagerness to put up a fight? We tell ourselves that the church’s task is to say “Here I stand!” against the changeable things of Earth, to resist those within a nation who are in an uproar — an uprising — against God. People who think and speak this way are bound to be more fearful, not less. For they’re bound to see a world filled with threats and targets, not fellow humans, fellow Americans, or even fellow Christians.

Yes, we even do it against each other. Think of the language that congregations and denominations use in times of debate over controversial issues. We stiffen our resolve to take a “position” or a “stance.” This is the language of warfare: when soldiers prepare to defend their position, they hold their weapons in a certain posture, a stance.

And worse still, we often add the adjective “biblical” to those nouns: the “biblical position” on sexuality, the “biblical stance” on marriage. We wield God’s word as if it were our Waffen, our weapon. In his new book, The Church of Us vs. Them, David Fitch laments how “biblical” has become “a power word in many churches. Its use can cut short a conversation as the so-called expert in the Bible, who alone has the authority to interpret it, exerts one position over another as orthodox.”

This use of “biblical” is an example of what Fitch calls a “banner.” Like soldiers rallying to a bloodied battle flag, Christians look to a word or phrase — a banner — that “forces people to choose sides quickly. It creates an enemy, the ‘liberal’ who is not biblical, and then makes the people who disagree into an ‘other.’ It sets into motion an antagonism that will ensnare everyone in its clutches. It sets up the church to be us vs. them.”

This use of “biblical” is an example of what Fitch calls a “banner.” Like soldiers rallying to a bloodied battle flag, Christians look to a word or phrase — a banner — that “forces people to choose sides quickly. It creates an enemy, the ‘liberal’ who is not biblical, and then makes the people who disagree into an ‘other.’ It sets into motion an antagonism that will ensnare everyone in its clutches. It sets up the church to be us vs. them.”

In short, we make “biblical” make enemies, as Luther’s followers and critics did in the Reformation. As Protestants and Catholics, and Protestants and Protestants, continued to do for centuries. And they thought that God’s Word helped them hold their stances in defense of their positions. (They could no other, God help them.)

Sisters and brothers, God’s word is not an enemy-making machine. And God’s refuge is not a fortress, sealed off from the shaking of this world. It’s not a fortified position or a defiant stance that lets our enemies know we mean business.

God’s refuge — our confidence — is that he is among us, a “very present help in trouble” (v 1). For Christians, God’s refuge is found in God’s Son, the Word made flesh who dwelt among us and dwells among us still. “God is in the midst of the city” (v 5) — incarnate, in the middle of the tumult and tottering, not towering distantly, defiantly above it.

We read in the psalm that this city is made glad by streams from a river, and perhaps we Christians should think of another city, the new Jerusalem of Revelation, through whose street flows “the river of the water of life” (Rev 22:1-2). As that city comes down from heaven, a voice says loudly, “See, the home of God is among mortals. He will dwell with them; they will be his peoples, and God himself will be with them; he will wipe every tear from their eyes. Death will be no more; mourning and crying and pain will be no more…” (Rev 21:3-4).

This city is both here and not yet here, but this is God’s refuge: God’s tear-drying, pain-healing, death-defeating presence among us.

So no, God’s fortress is no military installation. But God does give you orders. Not “Fight! Resist! Defend!” No, God commands his people to “Be still, and know that I am God; I am exalted among the nations, I am exalted in the earth” (v 10). Those are your orders.

Be still. As far as I can tell, this is the only time this particular Hebrew verb appears in the Bible. But it has cousins elsewhere in the Old Testament: wait, relax, stop… Or in an earlier psalm: “Refrain from anger, and forsake wrath. Do not fret — it leads only to evil” (Ps 37:8). So follow God’s order and be still: stop striving and losing; refrain from insisting that you can handle this by your own strength; don’t be frustrated that you can’t control what’s happening to you; loosen your grip over a situation bound to slip through your fingers. “Be still…”

“…and know that I am God.” Americans aren’t used to hearing “know” as an imperative. But this is another call to action: know God in prayer and meditation; know God in reflection on the Bible; know God in study of a Creation and creatures that proclaim the majesty of their Creator; know God through relationships with and service to others made in God’s Image.

Know God, and so learn that you are not God. If we truly want to know God, we must ask better questions than those we prefer to ask and contemplate more complicated answers than those that fall easiest from our lips.

So be still, my friends, and know that God is God. But there’s one more order: “I am exalted among the nations, I am exalted in the earth” (v 10b). Or, more literally, “I will be exalted among the nations, I will be exalted in the earth.”

This sounds more like a promise than a command, but I think we’re being invited to ask How? How will it come to be that God is exalted among the nations? How will the eternal God be exalted here, in a world of change and tumult and collapse and conflict?

Not with us looking down on a battlefield from behind the cover of walls and shields. God will be exalted among the nations because we go out among the nations. God will be exalted in the earth because that’s where we live and serve.

God will be exalted when we relax our stance, come out from behind our positions, and dwell among neighbors and enemies alike. We will be still together; we will know God together. Together, we will come into God’s refuge and God’s strength.

In Revelation 21, we learn that the gates of God’s city “will never be shut by day—and there will be no night there. People will bring into it the glory and honor of the nations” (Rev 21:24-26). As we reach the culmination of the Bible’s great drama, says David Fitch, “us vs. them is overcome.” If we don’t just hear these words but live these words, we will inhabit what he calls “the space beyond enemies.” We will invite more and more people to enter a city whose gates swing wide open.

Truly, sisters and brothers, “the Lord of hosts is with us; the God of Jacob is our refuge” (v 11). So be still, know that this God is God. Let your shields be burned and your weapons shattered, as you leave whatever fortress you’ve erected in order to go forth in love and peace and joy, that our God of refuge and strength may be exalted among the nations.

Here we go. We can do no other. God help us. Amen.