https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2KSNaN7wGao

Acknowledgements: Thank you to Beth Devlin for their assistance in conducting research for this article.

Among the many memorable and educational things that Sesame Street provided me as a preschooler—skills for counting in Spanish, for example, and knowledge about processing sugar beets and manufacturing crayons—perhaps the most important was the first opportunity to invite a Jewish person into my home: Mr. Hooper, Big Bird’s friend and beloved owner of the Sesame Street corner store. Mr. Hooper was sometimes curmudgeonly but always kind, a man who readily greeted his feathered friend with birdseed milkshakes and warm conversation, despite Big Bird’s tendency to mistakenly call him “Mr. Looper” or “Mr. Cooper.” Mr. Hooper was such a good-hearted neighbor that it was he who in 1978 rescued Bert and Ernie from Christmas disaster and taught them a critical lesson about the importance of generosity—in the very same episode that first revealed that Mr. Hooper was in fact Jewish and didn’t really celebrate Christmas, but Hanukkah instead.

Will Lee, the Brooklyn-born actor who played Mr. Hooper, considered his role on Sesame Street as the most significant in his long career. “I was delighted to take the role of Mr. Hooper, the gruff grocer with the warm heart,” said Lee in a 1970 interview with Time magazine. “It’s a big part, and it allows a lot of latitude. But the show has something extra—that sense you sometimes get from great theater, the feeling that its influence never stops.”

The influence of Sesame Street, which celebrated its fiftieth anniversary this past Sunday, has been the topic of much reflection this week, especially among the generations of people who grew up watching it. Sesame Street has changed significantly over the past half century as it has strived to meet the needs of new children facing new challenges in an ever complicated world. However, one feature of the show remains strikingly consistent: the fact that, as Lee put it, “its influence never stops,” especially in the mission of teaching its young viewers to understand, respect, and love their neighbors—including those who are religiously different from themselves.

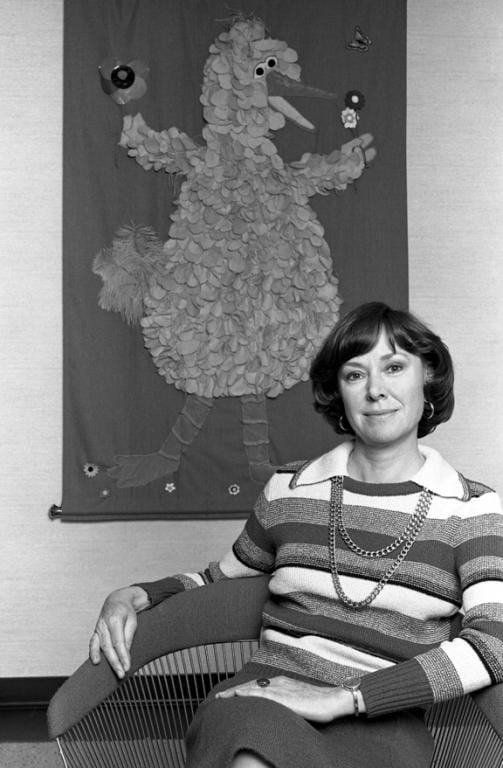

Joan Ganz Cooney, the Christophers, and the Call to Change the World Through Media and Communications

Sesame Street’s efforts to foster interfaith friendship and understanding owe in part to the particular background of one of its creators, Joan Ganz Cooney. As Michael Davis explained in Street Gang: The Complete History of Sesame Street, Ganz Cooney was the daughter of a German Jewish father and an Irish Catholic mother. Growing up in the 1930s and 1940s, she witnessed the impact of religion on the lives of the individuals and societies around her: how her mother drew inspiration from Catholic teachings to aid the poor during the Great Depression, how her father despised the anti-semitism he witnessed in their local community, and how her family grieved the death of a cousin who perished in a concentration camp in Nazi Germany.

Religious ideas and institutions would eventually shape Joan Ganz Cooney, too. As a young adult fresh out of college, she found a job in Washington, D.C., where she became involved with the Christophers, a religious community whose teachings would alter the trajectory of her personal and professional life. Founded by the Roman Catholic priest Father James Keller, the Christophers called Christians to live out the Gospel and serve as activists and missionaries in their own professions. Father Keller and the Christophers especially encouraged its members to pursue careers in media and communications, which they saw as offering powerful opportunities for Christians to have a positive impact on the world. According to the historian Jennifer Mandel, Ganz Cooney was deeply influenced by this movement, which not only urged her to lead of life of compassionate service and activism, but to do so in the particular field of film and television.

Modeling Interreligious Relationships Through Jewish-Christian Friendship

Sesame Street’s efforts to promote a more compassionate world has centered on depicting healthy relationships in an inclusive community comprising characters of different races, ethnicities, abilities, personalities, and—an aspect that is often overlooked—different religions. For most of its history, Sesame Street has taught young viewers how to live peaceably in a religiously diverse world primarily through stories about bonds of friendship between Christians and Jews. (The focus on Christian-Jewish relationships is not a surprise, given Ganz Cooney’s upbringing in a mixed Christian-Jewish family and Sesame Street’s location in New York City.) In addition to Mr. Hooper, the kind-hearted grocer, there have been other Jewish characters with whom Sesame Street characters have developed close and impactful relationships. For example, the Bear family is also Jewish, a fact revealed in the 2002 special Elmo’s World: Happy Holidays, in which Baby Bear introduced his best friend, Telly Monster, to Hanukkah and taught him how to spin a dreidel, all while they joyfully sang “The Dreidel Song.”

Sesame Street’s modeling of interfaith friendship and interpersonal pluralism was not limited to Muppets, but included the human characters, too. In one live-action segment, a Jewish child, Will, invited his Asian American classmate to have a playdate to make hamantaschen for Purim. As they walked through their neighborhood, Will and his mother pointed out and explained the Jewish things that were new to their friend—the Hebrew writing in the store windows, the yarmulkes worn by the men, the mezuzah hanging on the front door—all while cheerful klezmer music played in the background. Later, while the children’s homemade hamantaschen baked in the oven, Will’s mother read the boys a storybook about Purim, and the segment concluded with the boys happily drinking milk and eating their cookies. “They were delicious!” the Asian American friend declared. “I think I’m going to teach my mom how to make them!” This chain of person-to-person interfaith education—Will and his mother teaching the boy, and the boy then going home to teach his own mother—reveals the optimistic vision of Sesame Street, which has long endeavored to teach young children to understand and befriend people of different backgrounds, with the possibility that doing so will initiate an influence that can ripple outward and ultimately produce a more tolerant society.

Sesame Street’s efforts to promote understanding of Jews and Judaism was at once hyperlocal (taking place in Will’s kitchen, for example) and global in scope. It became an international enterprise when Sesame Street collaborated with its Israeli counterpart, Rechov Sumsum, to create a spin-off show, Shalom Sesame, which aimed to educate American audiences about Jewish culture and life. Running first in the early 1980s and revived in the 2010s, Shalom Sesame had some of the main characters familiar to American audiences—Big Bird and Oscar the Grouch, for example—but was conducted in Hebrew and English. With episodes such as “Mitzvah on the Street” and “Shabbat Shalom, Grover!”, Shalom Sesame taught American children about Jewish beliefs and practices and introduced them to the traditions and histories of holidays such as Hanukkah, Purim, and Passover.

Encountering Asian Religions on Sesame Street

As immigration from Asia increased over the past fifty years, the United States became more racially, culturally, and religiously diverse, and so, too, did Sesame Street. The show’s characters, once mostly Jewish and Christian, gradually expanded to include Hindus, Muslims, and other groups. For example, in 2008, Sesame Street had a segment called “Kids Talk About Holidays,” in which Elmo and his pet fish, Dorothy, interviewed children who spoke about how they and their families celebrated Ramadan, Kwanzaa, and Three Kings Day, as well as Christmas and Hanukkah. Short clips of children speaking about their holiday traditions emphasized shared practices—decorating with lights, giving gifts, gathering with relatives—as well as common feelings of familial love and spiritual connection. (“Elmo sure is surprised that holidays that can be so different can be so much alike!” Elmo declared.)

That same year, Sesame Street added its first Indian American character, Leela, who introduced young viewers to Hindu and Indian traditions. In the episode “Rahki Road,” for example, Leela taught Zoe, Telly Monster, and Chris about the exchange of rahki bracelets between brothers and sisters, and a “C is for Crafts” segment in 2018 taught children how to make paper lanterns for the Hindu holiday of Diwali. Other Asian traditions and celebrations soon followed. In 2019 Sesame Street celebrated Lunar New Year with a dragon dance featuring Elmo and Abby.

Although the past two decades have witnessed the introduction of many new religions, characters, and celebrations, much has remained the same in how Sesame Street has televised interfaith encounters and modeled how its young viewers could put pluralist ideals into practice. The show has continued to build children’s religious literacy by developing their basic knowledge of different beliefs and practices. Even more important, Sesame Street has remained committed to spreading a message about the power of meaningful and caring relationships with people of diverse backgrounds. As the show has consistently taught, the most important learning—about religion, and about everything else that matters—occurs in the context of friendship and community.

To be sure, the particular form of religious pluralism promoted by Sesame Street also has its limitations. For example, it has the potential to exclude those who do not have a recognizable world religion and do not adhere to beliefs and practices that easily fit the Protestant template of religion. It doesn’t engage in the differences that exist both within and between religious communities, nor the unequal relations of power that continue to exist and that strain relations between different religious groups.

In addition, Sesame Street’s efforts at religious inclusion have not always been met with enthusiasm. In 2017, when Sesame Street shared a Ramadan greeting on Twitter, the message caused a stir among people who criticized the show for not offering the same respect to Christianity. (Sesame Street, in reality, had celebrated Christian holidays since its earliest years.) Given the rise in Islamophobic attitudes in recent years, the angry reaction to the Ramadan tweet is not a surprise.

More than anything, though, the hostile reaction to the Ramadan tweet suggests that Sesame Street’s efforts to teach young people to be good neighbors in a multireligious world remain as important and necessary as ever. The question posed in the lyrics of the opening theme song offer a beautiful vision for what the show offers children now, in the fictitious world of Sesame Street, and what it can possibly build for a future reality:

Friendly neighbors there

That’s where we meet

Can you tell me how to get

How to get to Sesame Street?

In this moment, as religious hatred and violence continue to plague our world, I confess that more than ever before, I want to know how we can get to Sesame Street.