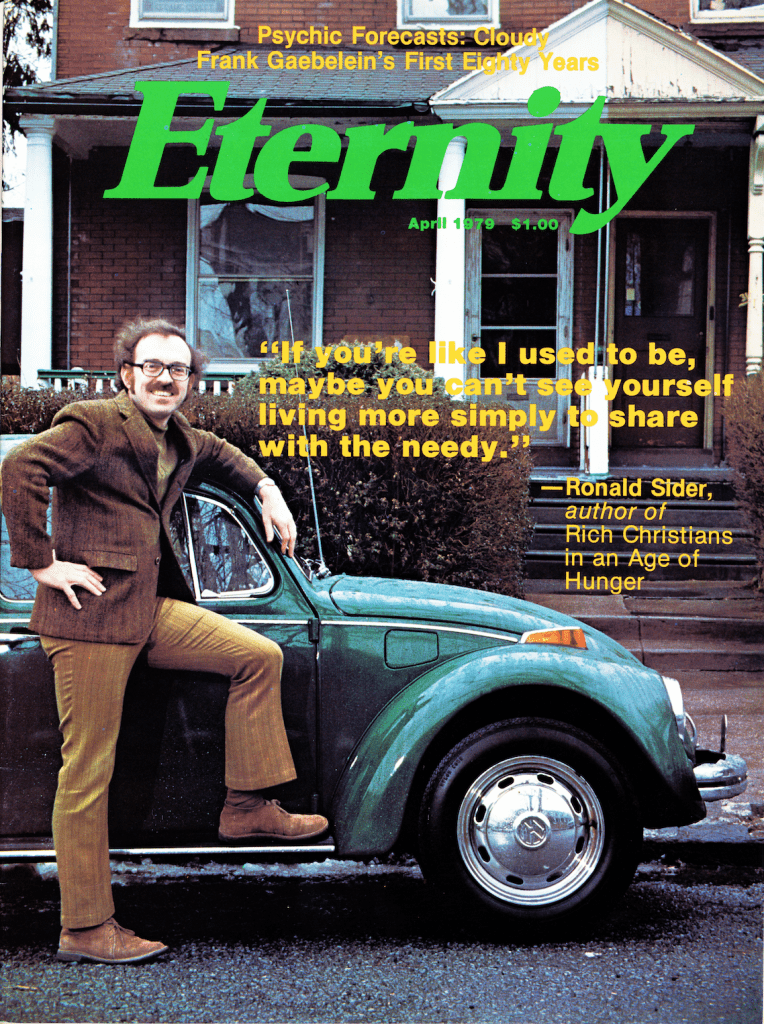

Ron Sider is perhaps most notable for his book Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger (1977). It contended for simple living, and it pushed for graduated tithes, the giving away of money at higher rates the more money you make. In short, the book articulated an anti-prosperity gospel.

Published in the 1970s, it resonated with some evangelicals suffering in the midst of economic recession and oil embargoes. And it provoked one of his critics, David Chilton, to write a book with the funniest—and most eye-rolling—title I’ve ever seen: Productive Christians in an Age of Guilt Manipulators (1981).

Though Sider sojourned among evangelicals for most of his career, at heart he was an Anabaptist country boy. He grew up in the 1940s on a 275-acre farm in rural southern Ontario, firmly ensconced in the close community of the nonconformist Brethren in Christ, a denomination equal parts Anabaptist and holiness. His mother wore a prayer veiling. His father rigorously kept the Sabbath. His cousin Roy Sider, an influential bishop in Ontario, preached that it was wrong to vote. Very few of the Brethren played organized sports or pursued higher education. Sider himself struggled with guilt over his “worldly” decision to wear a tie and to part his hair to the side. Sometimes burdened by the perfectionistic theology of his tradition, he was relieved when his father once cussed after a prized cow died.

Though Sider sojourned among evangelicals for most of his career, at heart he was an Anabaptist country boy. He grew up in the 1940s on a 275-acre farm in rural southern Ontario, firmly ensconced in the close community of the nonconformist Brethren in Christ, a denomination equal parts Anabaptist and holiness. His mother wore a prayer veiling. His father rigorously kept the Sabbath. His cousin Roy Sider, an influential bishop in Ontario, preached that it was wrong to vote. Very few of the Brethren played organized sports or pursued higher education. Sider himself struggled with guilt over his “worldly” decision to wear a tie and to part his hair to the side. Sometimes burdened by the perfectionistic theology of his tradition, he was relieved when his father once cussed after a prized cow died.

A sense of history also characterized his childhood. One side of his family—with the German last name of Wenger—could trace its roots back to the sixteenth-century Reformation in the Alps. Four centuries later the Wengers and Siders still identified with the cultural and political marginalization of the early Anabaptists. Each genealogical line contained ancestors who had been persecuted—sometimes even tortured and executed—by their Reformed and Catholic antagonists.

In his teenage years Sider abandoned many of his tradition’s cultural idiosyncrasies. He was a star athlete and an outstanding student in his one-room country school. One of the first in his family to attend college, he headed off to Waterloo Lutheran University in Ontario in 1958. Struggling with doubt over faith and modern science, he specialized in apologetics under John Warwick Montgomery, who was just emerging in the 1960s as an important evangelical opponent of the “death of God movement.” Montgomery, who would go on to debate atheist Madalyn Murray O’Hair and situation ethicist Joseph Fletcher in the late 1960s, taught Sider proofs for the resurrection of Christ and inspired him to pursue a life in academia.

When Sider received the news that he had received a full graduate fellowship to Yale University to study early modern European and Reformation history under noted Luther scholar Jaroslav Pelikan, he fell to his knees “breathless with gratitude” for this opportunity to be a faithful witness to Christ in the secular academy. At Yale Sider began his quest to become a college professor and InterVarsity campus advisor.

Sider’s research, however, led to an unexpected vocation as social activist. His dissertation subject, Reformation-era theologian Andreas Von Karlstadt, inspired his desire not to “let the doctrine of justification sell out sanctification.” Faith, he decided, required right behavior, not merely correct belief.

Seeking to understand poverty, racial inequities, and evangelical indifference in the face of urban blight, Sider experimented with urban living. He lived at first on the edge, then in the center, of New Haven’s black community. In 1967 he joined the NAACP and sat with his black landlords the night Martin Luther King was assassinated. In 1968 he participated in voter registration drives and encouraged the InterVarsity chapter at Yale to do so as well. These experiences, he remembers, “got me so concerned with racial issues that I felt I could not go on doing nothing but reading Latin and German for my dissertation.”

Seeking to understand poverty, racial inequities, and evangelical indifference in the face of urban blight, Sider experimented with urban living. He lived at first on the edge, then in the center, of New Haven’s black community. In 1967 he joined the NAACP and sat with his black landlords the night Martin Luther King was assassinated. In 1968 he participated in voter registration drives and encouraged the InterVarsity chapter at Yale to do so as well. These experiences, he remembers, “got me so concerned with racial issues that I felt I could not go on doing nothing but reading Latin and German for my dissertation.”

Despite his new interests, Sider did in fact finish the dissertation. Subsequently, Messiah College, his denomination’s leading institutional of higher education, hired him to teach at an urban satellite campus next to Temple University in Philadelphia. This move completed his shift away from history to social concerns. Instead of teaching classes on Reformation history, he focused on war, poverty, and racism. The Sider family lived in a largely black neighborhood in Germantown, and their sons went to a nearly all-black public school. Sider’s wife, Arbutus, organized parents’ groups and led marches on city hall. They attended several non-Mennonite churches: a black Presbyterian congregation and a semi-intentional community called Jubilee Fellowship.

But Sider’s concern for social injustices emanated largely from his childhood. He had observed his parents, who had never voted, adopt a needy child out of an “Anabaptist concern for peace and justice and for the poor.” Sider later explained that “I didn’t start out in life seeing the world from the windows of a Cadillac but rather [from] the other side.” His childhood—rural, Canadian, Anabaptist—gave him a “distance from the culture that … has been a real blessing.” These marginal identities and a Mennonite reading of Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount, which stressed radical generosity, animated Sider’s vision for simple living.

Sider continued to explore themes of poverty, the environment, race, and simple living during his long and productive career. But Sider’s early biography helps explain his retirement activities, which have focused largely on themes of peace. His most recent book—If Jesus Is Lord: Loving Our Enemies in an Age of Violence (2019)—is the third volume in a series. The first was an exploration of all the post-New Testament, pre-Constantinian church writings on killing. Titled The Early Church on Killing: A Comprehensive Sourcebook on War, Abortion and Capital Punishment (2012), it fit Sider’s long-held consistent life ethic. The second, titled Nonviolent Action: What Christian Ethics Demands But Most Christians Have Never Really Tried (2015), fit Sider’s interest in active peacemaking over passive nonresistance.

Sider continued to explore themes of poverty, the environment, race, and simple living during his long and productive career. But Sider’s early biography helps explain his retirement activities, which have focused largely on themes of peace. His most recent book—If Jesus Is Lord: Loving Our Enemies in an Age of Violence (2019)—is the third volume in a series. The first was an exploration of all the post-New Testament, pre-Constantinian church writings on killing. Titled The Early Church on Killing: A Comprehensive Sourcebook on War, Abortion and Capital Punishment (2012), it fit Sider’s long-held consistent life ethic. The second, titled Nonviolent Action: What Christian Ethics Demands But Most Christians Have Never Really Tried (2015), fit Sider’s interest in active peacemaking over passive nonresistance.

These books are a fitting bookend to Sider’s childhood. Indeed, they are authentic products of his Anabaptist heritage. But they are not mere exercises in identity politics. He clearly wants to show Christians of other stripes that peace is biblical—and even that it works. If Jesus Is Lord marshals example after example of successful unarmed insurrections against oppressive regimes. One of the most convincing, he says, involved over a million nonviolent Filipino demonstrators prevailing against the vicious dictator Ferdinand Marcos in the 1980s. Summarizing all the known cases of both major armed and unarmed insurrection from 1900 to 2006, Sider concludes, “Nonviolent resistance campaigns were nearly twice as likely to achieve full or partial success as their violent counterparts.”

Ron Sider is still trying to evangelize the evangelicals.