Like other faith communities around the world, our Lutheran church is finding ways to worship apart from a physical sanctuary. What we watch online has liturgy, prayers, hymns, Scripture readings, and a sermon. But one element is conspicuously absent: the sacrament of Holy Communion, which we haven’t received since a Lenten evening service the Wednesday before large public gatherings in Minnesota were suspended.

In the age of COVID-19, what does it mean that Christians can’t gather in person to participate in the ritual they call Communion, Eucharist, or the Lord’s Supper?

Can sacraments, like work and education, take place remotely? While some theologians who specialize in digital issues argue for online communion, others conclude that “in virtual worship, we remain ultimately uncommuned in a full sense.” Warning that sharing masses online as anything more than a temporary measure “would amount to wishing for a kind of ‘disincarnation’ of Christ,” one French Catholic theologian urged his bishop to challenge their government’s restrictions on gathering for worship. Our church’s denomination has formally discouraged the practice of virtual communion, and even suggested that the disruption of “fasting” from that sacrament “gives us the time and space to examine our understanding of and practices around Holy Communion.”

Today’s post is dedicated to such examination. I’m no theologian, so if you really want to dig into the issues related to virtual communion, you might check out this podcast (co-hosted by a colleague from Bethel Seminary). But as a historian, I thought I’d share the story of a Christian movement whose members didn’t take Communion for some 350 years. They weren’t guarding against the threat of disease, but a danger described by the apostle Paul:

Whoever, therefore, eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be answerable for the body and blood of the Lord. Examine yourselves, and only then eat of the bread and drink of the cup. For all who eat and drink without discerning the body, eat and drink judgment against themselves. For this reason many of you are weak and ill, and some have died (1 Cor 11:27-30)

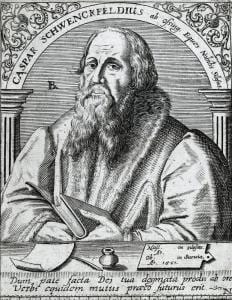

Our story starts in 1518, in what’s now Poland. An aristocrat and royal counselor named Kaspar Schwenkfeld von Ossig experienced a “visitation of the divine” that led to a profound religious conversion. Though never ordained, Schwenkfeld began a new career as a Protestant reformer in the region of Silesia.

Initially influenced by Martin Luther’s writings, Schwenkfeld began to break with Wittenberg in 1524. He warned local pastors that Luther’s understanding of salvation by grace alone went so far to avoid works righteousness that it minimized the importance of changed lives and changed behavior. Believing “that reformation without reformed lives was meaningless,” explains Schwenkfelder pastor Jack Rothenberger, Schwenkfeld hoped that “the personal experience of the living Christ” would bring about a “maturing awareness on the part of a believer that he or she is empowered daily by Christ to live for God and others.”

Schwenkfeld hoped to find a “Middle Way” between Catholic and Lutheran positions on justification and sanctification, but it was his attempt at mediating the debate over Communion that led to his final rupture with Luther.

As they read Paul’s description of the Last Supper in 1 Corinthians 11, Schwenkfeld and his colleagues in Silesia decided to re-interpret “This is my body” as “My body is this”: the physical bread was not Jesus’ body, but Jesus’ body was spiritual bread. After the two men discussed the issue in Wittenberg in 1525, Luther held on to his belief in consubstantiation and dismissed Schwenkfeld’s view as a variant on that held by his Swiss rival Ulrich Zwingli: that Christ was spiritually, but not physically, present in the meal. But Schwenkfeld insisted later that there was “a vast difference” between his view and that of Zwingli (or John Calvin): “For although we say in both cases, as is certainly true, that the body and blood of Christ are eaten and drunk only spiritually, nevertheless we are indeed far from one another as to what it means that the body of Christ is spiritually eaten in his Supper, and his blood spiritually drunk.”

While they would later be accused of minimizing the importance of the sacrament, Schwenkfeld’s decision to stop taking Communion actually stemmed from his high view of it. “The divine presence of Christ in the power of the Holy Spirit is uniquely present when we gather around the table,” preached Schwenkfelder pastor David McKinley in this 2015 sermon.

And that’s why Paul would teach in 1 Corinthians 11 that we ought to take special care in approaching this meal, so as not to do it flippantly or carelessly or in vain. Because if we do that, we could be guilty of partaking the Body and the Blood of the Lord in an unworthy manner.

On April 21, 1526, Schwenkfeld and like-minded pastors issued a circular letter claiming that “the Holy Sacrament or mystery of the body and blood of Christ has not been observed according to the Gospel and command of Christ.” Rather than invite God’s judgment for unworthy participation in the Lord’s Supper, “we admonish men in this critical time to suspend for a time the observance of the highly venerable Sacrament.”

They called it the Stillstand — a sacramental “standing still,” until Christians had demonstrated their worthiness to take Communion.

What could have made 16th century Christians unworthy of the bread and the cup? Beyond their general concern that the Reformation was not reforming lives, Schwenkfeld and followers of his “Middle Way” were particularly agitated that a fracturing church defied Jesus’ and Paul’s exhortations to Christian unity. How could Lutherans and Catholics be worthy to receive what they understood to be Christ’s body when their disagreement on that very sacrament was tearing apart the Body of Christ?

And so, historian Peter Erb observes, the Schwenkfelders became “one of the few movements whose beginnings were the result, in fact, of ecumenical, not sectarian concerns.”

(That from a 2006 article that manages to connect the Schwenkfelder story to The Da Vinci Code. You can also read Erb’s summary of Schwenkfeld’s life and thought in an 1989 issue of Christian History Magazine occasioned by the 500th birthday of that “forgotten reformer.”)

From 1526 through his death thirty-five years later, Schwenkfeld abstained from the Lord’s Supper. While he agreed that a sacrament required both spiritual grace and a material sign, he taught that believers could still receive the former without participating in the latter, as in this 1531 argument:

Neither Christ, nor his grace, nor the Spirit is bound to the use of the sacraments, nor attached to any external thing. Through Christ, God effects such a mystery freely in the Spirit where and when he finds the soul prepared through faith that it desires his grace and activity, be it immediately before the use of the sacrament, in the use, after the use, without the use, and with the use. Just as he works before the sermon, in the sermon, without the sermon, and with the sermon, independently in divine spiritual freedom…. Should such use occur apart from the use of the sacraments, it must nevertheless take place to a greater degree and more powerfully where the institution of Christ is followed also externally and practiced in obedience of faith with correct understanding and use. Where these two parts — the correct understanding and use — do not obtain, then it is better to omit [the sacraments] and apprehend the grace of God in other ways, so that the individual does not receive death, punishment, and condemnation where he supposed he would find life and salvation, as was the case in Corinth.

In his book on Schwenkfeld, Paul Maier concluded that “outer communion remained only a theoretical possibility with Schwenkfeld, while the inner observance received the predominating emphasis in his theology. He taught his followers that they were able to partake of Christ spiritually ‘every day, every hour, yes every moment’” — just as Jesus had enjoyed a “spiritual supper” with his disciples (John 6) and with the Samaritan woman at the well (John 4). “As often as a man senses divine sweetness in Christ, comfort, joy, love, grace, and mercy,” Schwenkfeld assured his followers, “as often as he has a foretaste of eternal life, he holds with the Lord his Supper.”

After Schwenkfeld’s death in 1561, the movement that took his name maintained what Erb calls “an open conspiracy”: followers met in private and adhered to Schwenkfeld’s teachings, but some continued to attend other churches in public. By the 18th century, persecution led the Schwenkfelders to seek new homes. After finding temporary asylum with the Moravians of Herrnhut in 1726 (the 200th year of the Stillstand), forty Schwenkfelder families migrated to Pennsylvania in 1734. By the early 19th century, there were no Schwenkfelders left in Europe.

According to Howard Kriebel’s history of the Schwenkfelders in Pennsylvania (one of the 1.4 million books now available from the National Emergency Library), that community began to discuss ending the Stillstand in the 1840s, but the first Schwenkfelder celebration of the Lord’s Supper in America didn’t happen until 1877. Some waited until the 1890s.

Today, the Schwenkfelder movement consists of a couple thousand people attending five churches in southeastern Pennsylvania. Those at Central Schwenkfelder Church in Lansdale now take Communion several times a year, but Rev. McKinley closed his 2015 sermon on Schwenkfeld’s Stillstand with words that all Christians can appreciate:

When we approach the Lord’s Supper, we realize that there is something deeper taking place. God is calling us to a deeper walk, a deeper devotion, a deeper level of faith and dependence on Christ, represented in food: the bread and the cup.