The streets were empty of children. Fear stalked the town. People kept to themselves… Churches canceled services.

Sunday school classes were held over the radio. Stores and theaters closed.

Not 2020, but 1950: Wytheville, Virginia — about 25 miles from where my parents now live, in a town whose governing council asked that ambulances from Wytheville not stop there on their three-hour drive over the mountain roads leading to the hospital in Roanoke.

“People bathed in Clorox,” recalled a 2002 retrospective in the Roanoke Times, “washed their hands in rubbing alcohol, wore pouches around their necks filled with garlic and onions and other folk remedies. A local bank spritzed its bills with fly spray, hoping to kill off money-borne infection.”

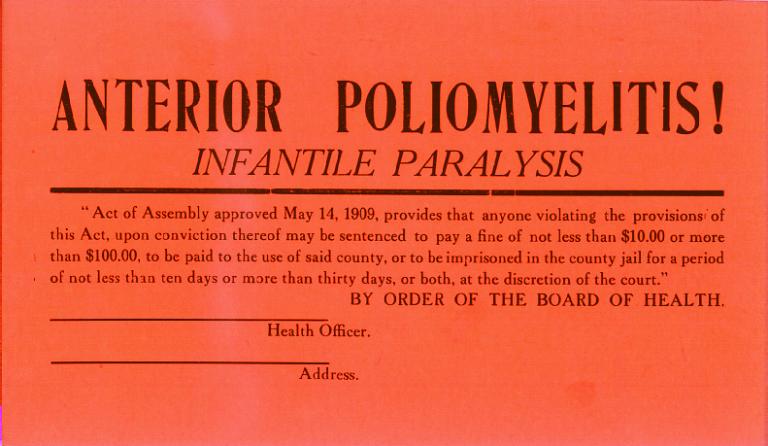

Not COVID-19, but poliomyelitis: the terrifying disease resulting from a virus attacking the nerve cells that move muscles. In its most acute form, polio causes sudden paralysis and even death, as victims lose the ability to breathe.

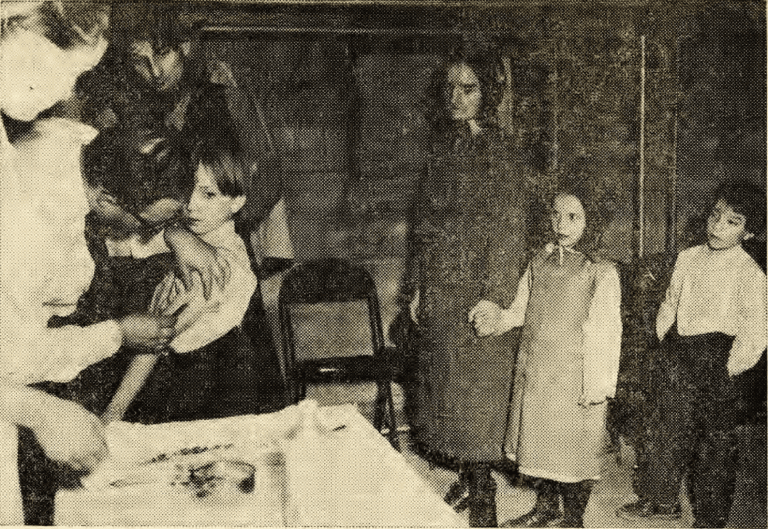

People of all ages caught polio, including the man who had been president throughout most of the Great Depression and Second World War. But it was particularly dangerous for children like Johnny Seccafico, the toddler son of the Wytheville Statesmen’s second baseman, who couldn’t move his limbs and, at first, was considered too sick to be placed inside one of the few iron lungs available, the machines that breathed for those unable to do so on their own.

During 1950’s “summer without children” — when Wytheville parents kept their kids away from swimming pools, parks, churches, and other public places — almost 200 of the town’s 5,500 residents contracted polio: 100 times the national rate. Then two years later, the disease surged around the United States, paralyzing over 20,000 Americans. 1952 marked the worst outbreak of a disease that had haunted the American imagination since 1894, when 18 people died and 132 more were paralyzed in Vermont.

“At times,” wrote Clyde Foushee in 1951, “you have perhaps wondered what you would do if polio should strike one of your children.” A Presbyterian pastor from South Carolina, Foushee asked Christian Century readers to bring to mind anxieties and assurances that were probably already familiar:

…you keep saying to yourself, “Don’t get panicky. This situation demands steady nerves and level heads.”

Your wife is calm and composed. Her eyes say, “Don’t get excited. We’ll carry this cross together.”

But as the hypothetical child “looks at the big iron lung” and struggles not to cry, Foushee had his readers imagine how they’d pray:

Alone with God, you give vent to your pent-up feelings. You beg God to subdue the fevered tempest before it leaves your child with lifeless or twisted limbs. You try desperately to persuade God to do your will. How gladly you would take the place of your child if she could only be set free.

In the end, his pastoral counsel was that parents simply ask God for “the grace to accept thy will and the courage never to doubt thy wisdom.” But Christians joined other Americans in anticipating word of a cure. When news of a successful vaccine came in 1955, The Christian Century lavished praise on Dr. Jonas Salk and other scientists. “We hope,” the editors wrote that April, “that services of thanksgiving to God are being held in millions of homes and thousands of churches for this answer to prayer, this successful completion of a decade of intensive concentration on medical research.”

Polio did not disappear from the American consciousness. Too many people had survived serious cases to be ignored. In 1957 the Baptist General Conference’s magazine reported on a Minneapolis church that installed a ramp to aid wheelchair-bound polio survivors. Three years later it ran an ad for a “middle-aged Christian woman” willing to “live with and care for” a paralyzed child.

But as the Century editorial had predicted, polio soon joined smallpox among the medical nightmares that became “nothing more than dreadful memories” in American society. Its power to terrify became metaphorical, as when FBI director J. Edgar Hoover warned Christianity Today’s readers of the continuing dangers of Communism: “Like an epidemic of polio, the solution lies not in minimizing the danger or overlooking the problem—but rapidly, positively, and courageously finding an anti-polio serum.” Just as polio had a vaccine, America had an “anti-communist serum” in its “Judaic-Christian tradition, the power of the Holy Spirit working in men.”

Incidentally, Salk’s vaccine (which used killed polio virus to trigger the production of antibodies) was so massively popular in the U.S. that his rival Albert Sabin had to go to the Soviet Union in 1957 to conduct field studies of his live-virus alternative, which could be administered orally. It was approved for American use in 1961 and remained popular until a federal panel advised against it in 1999. (More on that before we’re done…)

But not everyone was willing to vaccinate themselves or even their children. In the late 1970s, Christian objections to vaccination led to two of the last significant polio outbreaks in the developed world.

Worse yet, cross-Atlantic visits brought the same disease to unvaccinated Dutch Reformed enclaves in Canada. From there it spread to a different American Christian population that had always been somewhat suspicious of government-sponsored vaccination initiatives: the Amish, fourteen of whom suffered paralysis from polio in 1979.

Objections to vaccinations didn’t disappear from either group, but opposition did soften. As early as July 1979 the CDC estimated that the majority of America’s Amish had taken at least one dose of Sabin’s live-virus vaccine. By the start of the 1980s, the United States had been declared polio-free.

More than seventy more unvaccinated Dutch children contracted polio in 1992-1993, and there was a small flare-up of the disease in a Minnesota Amish community in 2005. But that last incident was quickly traced back to an immunocompromised infant who had been exposed to the live form of a polio virus still used in Sabin’s oral vaccine — most likely via someone who had been vaccinated somewhere outside of North America.

But as Atlantic writer Olga Khazan reported in 2015, America’s “anti-vaxxer” movement continues to point to that Christian community as a model of vaccine-free health. “When we think of Amish people,” began one such 2013 article,

we think of a simple life, free of modern advancements. Most of us view them as foolish for not using the advantages of convenient technology and even look down on them for not conforming to the norms of mainstream society. But if we look at the statistics, the Amish are much healthier than the rest of America.

Why? Before getting to other, more plausible arguments, that author claimed (without peer-reviewed evidence) that a lack of autism and learning disabilities among the Amish stemmed from their supposed refusal to vaccinate their children.

Most Amish do vaccinate (and help their neighbors during the COVID outbreak), and most other conservative Christians (including staunch Calvinists) strongly support the practice. But seventy years after the polio panic in Wytheville, some Christians still deny the science behind vaccination — or object to vaccines that originated with fetal tissue research. (Numbers are hard to discern, in part because anti-vaxxers are increasingly invoking religious exemptions, as fewer and fewer states accept “philosophical” objections.)

As we look ahead to the day when a coronavirus vaccine makes social distancing and shelter-in-place orders as distant a memory as iron lungs, I hope that more and more Christians will heed the advice of the Methodist pastor I quoted in my post on the 1918 influenza pandemic:

Christians do not discount their faith in the omnipotence of their God by keeping their bodies and homes and streets clean and nongerm producing; by using care in traffic and travel, accepting vaccination, sprays and disinfectants and keeping God’s own laws of health and life. Any other course is the fruit of ignorance and false teaching. (emphasis mine)