I stepped over the low stone wall and walked down the path to the river. The water of the Brazos stood still in the summer evening, reflecting only a slightly blurred image of the I-35 bridge crossing into downtown Waco. Behind me stretched the green lawn of the Fort Fisher campground. I had just walked from the Texas Ranger Museum, skirting the modern edge of the old First Street Cemetery, as I made my way down to the river bank.

The historian in me knew I had just walked across a graveyard. Yet no visible evidence of it remains. Unlike the part of the cemetery closer to the highway, the upper terrace of the old First Street Cemetery, no headstones marked the resting places of the the early Waco families buried nearer the river. Only a very recent historical marker, placed near the (now) main entrance of First Street Cemetery, indicates that the nineteenth-century graveyard once encompassed a much larger area. “In the 1890s,” the marker states, “burials were dug in tiers which resulted in the disturbance of previous burials. In 1968, after years of neglect, the Waco City Council voted to relocate graves and/or markers in the lower terrace of the cemetery to the upper terrace. The lower terrace became a recreational campground know as the Fort Fisher Park.”

Waco families buried nearer the river. Only a very recent historical marker, placed near the (now) main entrance of First Street Cemetery, indicates that the nineteenth-century graveyard once encompassed a much larger area. “In the 1890s,” the marker states, “burials were dug in tiers which resulted in the disturbance of previous burials. In 1968, after years of neglect, the Waco City Council voted to relocate graves and/or markers in the lower terrace of the cemetery to the upper terrace. The lower terrace became a recreational campground know as the Fort Fisher Park.”

In other words, part of the cemetery has disappeared.

The origin of First Street Cemetery dates all the way back to 1852 when the thriving Waco community established their first city burial ground on the south bank of the Brazos River. Originally it comprised five acres purchased for the city and augmented by an additional two acres from the local Masonic lodge. A third area was added in 1868/1869 by the local lodge for t he International Order of Odd Fellows. An 1869 city map shows the property that became a 4th addition to the cemetery in 1882.

he International Order of Odd Fellows. An 1869 city map shows the property that became a 4th addition to the cemetery in 1882.

“Mom,” my daughter called me. We were taking an evening walk through the cemetery together. “I think this person must hav e been a preacher.” She had found a cemetery marker that looked like a lecturn with a Bible on top. Sometimes I can talk her into going with me on my evening walks. First Street Cemetery is an easy distance for us from where we live on Baylor campus as a Faculty-in-Residence family, and she likes to look at the carvings on the tombstones. First Street Cemetery sits right across University Parks Drive in the shadow of the McLane Football Stadium. As I watched my daughter walk slowly through the old tombstones, kneeling to read the names and find the dates, I knew she could only see some of the history that lay buried here. Only the markers of some of the possibly thousands of people remain.

e been a preacher.” She had found a cemetery marker that looked like a lecturn with a Bible on top. Sometimes I can talk her into going with me on my evening walks. First Street Cemetery is an easy distance for us from where we live on Baylor campus as a Faculty-in-Residence family, and she likes to look at the carvings on the tombstones. First Street Cemetery sits right across University Parks Drive in the shadow of the McLane Football Stadium. As I watched my daughter walk slowly through the old tombstones, kneeling to read the names and find the dates, I knew she could only see some of the history that lay buried here. Only the markers of some of the possibly thousands of people remain.

Although many of the graves in the cemetery have been affected by the changing urban landscape around it, it is the last addition to the cemetery that seems to have been affected the most. It is the part that has mostly disappeared.

Would it surprise you to learn that this is the part of the cemetery that was dedicated to Waco’s non-white population?

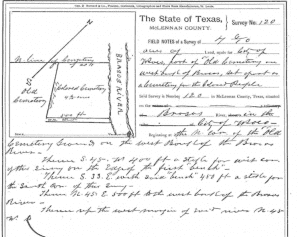

As the 1882 survey map states, it was land “set apart as a Cemetery for the Colored People.” For many years, not very many people in Waco knew about this Black cemetery. T. Bradford Willis and John Griggs wrote in a short paper “The Predominately African-American Section of First Street Cemetery of Waco, Texas”, that “This map with a ‘formally designated  colored cemetery’ at First Street Cemetery does not appear in the known written histories of Waco and McLennan County.” And some of the people who later learned about it seem to have minimized its existence–calling the area an “‘informal burial ground’ for paupers.” As Willis and Griggs have written, “this section of First Street Cemetery/Fort Fisher Park has been dismissed by some of having any historical significance. It has been referred to many times in local newspaper articles as just an informal burial ground for paupers.” A decision made by the City of Waco in 1968 helped erase the memory of this cemetery when the lower terrace burial site was turned into a recreation area. While the graves were supposed to have been relocated and reburied to the upper terrace of First Street Cemetery, they apparently were not. A construction project begun in 2007 unearthed some 250-300 unmarked graves. A significant number of these human remains were determined to be African American (according to the archaeologist who supervised the project), just as the 1882 survey map suggests.

colored cemetery’ at First Street Cemetery does not appear in the known written histories of Waco and McLennan County.” And some of the people who later learned about it seem to have minimized its existence–calling the area an “‘informal burial ground’ for paupers.” As Willis and Griggs have written, “this section of First Street Cemetery/Fort Fisher Park has been dismissed by some of having any historical significance. It has been referred to many times in local newspaper articles as just an informal burial ground for paupers.” A decision made by the City of Waco in 1968 helped erase the memory of this cemetery when the lower terrace burial site was turned into a recreation area. While the graves were supposed to have been relocated and reburied to the upper terrace of First Street Cemetery, they apparently were not. A construction project begun in 2007 unearthed some 250-300 unmarked graves. A significant number of these human remains were determined to be African American (according to the archaeologist who supervised the project), just as the 1882 survey map suggests.

The cold hard truth seems that, in 1968, the (I suspect mostly white) leaders of Waco turned an old Black cemetery into a campground without properly removing most of the graves or recognizing the historic site. While Waco has worked hard to correct this past mistake, there is only so much that can be done. Much of the rich cultural heritage and history of Waco’s early Black and Brown inhabitants has simply been erased–the “Many prominent African-Americans” who were buried in First Street Cemetery, “including Knights and Daughters of Tabor, a member of the Mosaic Templars of America, a 19th century Texas legislator, a 19th century member of the Waco City Council, a chairman of the board of Paul Quinn College, one of the original twenty-one settlers of Waco Village, many U.S. veterans, and former slaves” are simply gone (at least until DNA tests can confirm the identities of some of the bodies). This isn’t all the fault of the 1968 decision. It is also because of the overall neglect of the historic site. Poor records were kept in the late nineteenth century, and throughout the twentieth-century, First Street Cemetery was simply not deemed enough of a priority by Waco to be kept in good repair.

Except for a few parts of it.

A Waco Tribune Herald article notes the cemetery is “Waco’s oldest burying ground and contains Confederate soldiers, pio neer politicians, slaves, ministers and workers of Mexican and Chinese descent.” Can you guess, out of that list, which graves were taken better care of? As I wandered through the visible tombstones that day with my daughter, I found that in 1976–just a few years after the Waco City Council had covered the Black cemetery with a campground–the Appomattox Chapter No. 2394 of the United Daughters of the Confederacy had erected a memorial stone for the Confederate Veterans

neer politicians, slaves, ministers and workers of Mexican and Chinese descent.” Can you guess, out of that list, which graves were taken better care of? As I wandered through the visible tombstones that day with my daughter, I found that in 1976–just a few years after the Waco City Council had covered the Black cemetery with a campground–the Appomattox Chapter No. 2394 of the United Daughters of the Confederacy had erected a memorial stone for the Confederate Veterans

buried in First Street Cemetery while chapter #2600 of the United Daughters of the Confederacy restored the marker for Nathaniel Jackson Wollard on the 26 of April, 1998.

Meanwhile, the descendants of Black slaves who lived and died in Waco still have no marker at their original gravesite.

Historical commemoration says more about the people who erect the statues and the markers than it does about the people commemorated. In twentieth-century Waco, we chose to build a park over the bodies of dead Black Americans while erecting new markers commemorating the white soldiers who fought to preserve slavery. The bad news is that this choice says a lot about the people we were–people complicit in racism. The good news is that we can choose, starting right now, to be better.

Just something to think about next time someone complains about taking down a Confederate statue.