Earlier this week Jerry Falwell Jr., president of Liberty University and one of President Trump’s leading evangelical supporters, once again found himself at the center of controversy. And once again, Falwell had no one to blame but himself. This time, the matter at hand wasn’t his decision to keep Liberty open against public health recommendations, nor was it his threat to sue journalists who covered the decision, nor was it his tweeting a racist image of Gov. Northam. At issue, rather, was a photo Falwell posted to Instagram—a photo in which he stood, arm in arm with a young woman who is not his wife, each with their shirts tugged up, their pants partially undone, and, in the case of Falwell himself, his underwear clearly visible beneath his slightly protruding belly. One of his hands rested just beneath the girl’s breast, the other clasped a glass of “black water,” according to his own caption (translation: definitely not alcohol).

When the internet erupted in consternation, Falwell’s friends came to his defense. Malachi O’Brien, a fellow at Falwell’s Falkirk Center, initially claimed on Twitter that the man in the photo was not Falwell. Before long O’Brien deleted that tweet, conceding that it was indeed Falwell, but asserting that the photo had been “taken out of context.”

O’ Brien was right. To understand Falwell’s proclivities, his behavior must be situated in terms of the longer history of white evangelical masculinity.

To be sure, the context O’Brien was referring to was the party Falwell hosted on his yacht inspired by the Netflix mocumentary series Trailer Park Boys. While on vacation, Falwell and “lots of good friends”—friends who apparently included a number of young, somewhat scantily clad coeds—recorded their revelries on video. (Judge for yourself whether the video of the president of one of the country’s largest Christian universities makes the situation more or less problematic.)

Of course, this isn’t Falwell’s first brush with impropriety. In 2019, the New York Times reported on the intricate, tabloidesque tale of “the friendship between Mr. Falwell, his wife and a former pool attendant at the Fontainebleau hotel in Miami Beach; the family’s investment in a gay-friendly youth hostel; purportedly sexually revealing photographs involving the Falwells; and an attempted hush-money arrangement engineered by the president’s former fixer, Michael Cohen.”

Months after the New York Times story broke, Politico published an investigative report on the “culture of fear and self-dealing” Falwell fostered at Liberty. That story included another incriminating image of Falwell, a 2014 photo of the university president partying at Miami Beach’s WALL nightclub. Falwell initially denied that he’d visited the club* and alleged that the images were photoshopped, but the next day new photos appeared depicting Falwell and family members at the club, some of whom can be seen holding alcohol.

The real problem for Falwell wasn’t his penchant for clubbing, his apparent alcohol consumption, or even his tastelessly insufficient attire, but rather the seeming hypocrisy of it all. Liberty University has a strict code restricting the behavior of students by prohibiting the consumption of alcohol and nicotine, dictating modest dress (including skirts no shorter than two inches above the knee and “modest one-piece” swimsuits), and prohibiting all “media or entertainment that is offensive to Liberty’s standards and traditions,” including “lewd lyrics, anti-Christian message, sexual content, nudity, pornography, etc.” as well as all “sexual relations outside of a biblically ordained marriage between a natural-born man and a natural-born woman.” Moreover, in all personal relationships, students are “to know and abide by common-sense guidelines to avoid the appearance of impropriety.” Failure to abide by these rules results in fines, disciplinary community service, or withdrawal from the university.

By these standards, Falwell himself appears to be nothing less than the poster boy of the hypocrisy of family-values evangelicalism. But again, context is helpful. As I trace in my book Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation, for many conservative evangelicals, family values don’t mean what we might think they mean.

By these standards, Falwell himself appears to be nothing less than the poster boy of the hypocrisy of family-values evangelicalism. But again, context is helpful. As I trace in my book Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation, for many conservative evangelicals, family values don’t mean what we might think they mean.

Falwell’s antics are sometimes contrasted with the more esteemed leadership of his father, Jerry Falwell Sr., but the older Falwell helped create the masculine ideal that would one day be embodied, with all its foibles, by his own son and heir apparent. At Thomas Road Baptist Church, Falwell Sr. promoted a particularly militant Christianity closely linked to a rugged masculine ideal. The church was an “army equipped for battle,” Sunday school an “attacking squad,” and Christian radio “the artillery.” Enemies abounded: feminism, communism, government intervention in the family, IRS interference in Christian (segregated) schools, and “rampant homosexuality.” It was up to Christian men—strong, militant men—to fight this “holy war.” For Falwell Sr., Jesus himself took the form of a holy warrior: far from the effeminate, delicate man depicted in images sporting “long hair and flowing robes,” the Reverend Falwell’s Jesus “was a man with muscles…Christ was a he-man!”

Other evangelicals, too, joined Falwell Sr. in propping up a rugged masculine ideal. James Dobson, the father of family-values evangelicalism, emphasized the role of testosterone as part of God’s blueprint for manhood. Testosterone made men aggressive, but it also made them heroes, protectors of women and children, church and nation. Christian sex manuals made clear that a man’s God-given testosterone had sexual side-effects, too. God filled men with sexual desire but gave them little capacity for restraint. It was instead up to godly women to ensure virtue by dressing and behaving modestly around men who were not their husbands, and by fulfilling every sexual need of the men who were.

In 1973 in her book The Total Woman, Marabel Morgan instructed women on how best to do so. She urged housewives to keep up their “curb appeal,” to “look and smell delicious,” to be “feminine, soft, and touchable”—at least if they wanted husbands to come home to them and not take up with their secretaries. To keep a husband’s interest, Morgan was a strong believer in the power of costumes in the bedroom (or kitchen, living room, or backyard hammock,” so that when a husband opened the front door each night it was like “opening a surprise package.” A woman was to love her husband “unconditionally,” which meant making herself sexually available to him. Her book advised women not only on how to be submissive sex partners, but also “sizzling” lovers. It would eventually sell more than ten million copies.

The motif of a man’s sexual desire and a woman’s obligation to meet that desire runs through conservative white evangelicalism, from the 1970s to the present. In the early 2000s, as the 9/11 terror attacks reinvigorated calls for militant Christian manhood, conservative evangelicals embraced this equation with renewed vigor. According to Seattle megachurch pastor Mark Driscoll, women performing oral sex on their husbands was a biblical mandate; if they thought they were “being dirty,” chances are they were pleasing their husbands. The otherwise inexplicable “smokin’ hot wife” phenomenon that swept the world of conservative evangelicalism is part of this same impulse.

When men stepped out of line—when they were unfaithful to their wives, when they abused women or even young girls, when they engaged in same-sex affairs, it was often the wife who bore the blame for failing to meet her husband’s sexual needs. The perpetrator, meanwhile, was awarded with forgiveness.

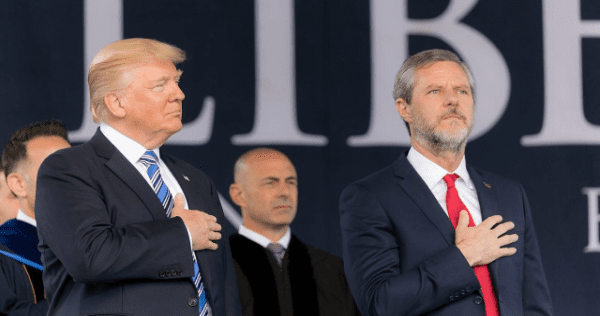

Given this history, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that white evangelicals had little difficulty dismissing allegations of sexual misconduct against Donald Trump in 2016. Nor should Falwell Jr.’s ardent support for the president be in any way puzzling. Already in 2012, Falwell had invited Trump to Liberty University. When the visit stirred some controversy after Trump told students they should “get even” with those who wronged them in business, Falwell jumped to Trump’s defense. This posture was fully compatible with Christian teaching in that it was representative “of the ‘tough’ side” of Christianity.

That this toughness went hand-in-hand with crassness was understood. The same testosterone that made men aggressive also made men heroes. Boys would be boys.

This isn’t Falwell’s first attempt to depict himself in terms of a virile masculinity, of sorts. Scrolling through his Instagram one finds videos of Falwell pumping iron, an image of him carrying Liberty University cheerleaders on his shoulders, and enough shirtless photos to make even someone like Putin jealous.

The fact that Falwell has been able to maintain this posture for so long suggests that his behavior doesn’t ultimately entail the betrayal of family values evangelicalism, but rather that crassness, masculine sexual prowess, and abuse of power can be found at the very heart of conservative white evangelicalism.

*Correction, of sorts: As Napp Nazworth helpfully pointed out to me on Twitter, Falwell Jr. did not actually deny that he had been at the nightclub, simply that there was evidence of him being at the nightclub.