Christmas is a time to look back on the year almost passed by, and the findings and discoveries of that year. So what was new or unexpected? In 2020, the short answer was: a huge amount of the unexpected, and virtually none of that good. As Charles Dickens said, it was the worst of times, it was the … oh wait, no, it was just the worst of times.

Having said that, on a personal level, I have a literary and/or cinematic discovery to report. It involves Katherine Anne Porter, Sam Peckinpah, the Mexican Revolution, a heretical pseudo-gospel, and the fall of Muslim Spain. No, really. It also, in a bizarre way, encapsulates many of my longest-standing interests and obsessions. Bear with me on a somewhat strange voyage, during which I shed a little light on what is widely regarded as one of the greatest of American films. Call it my Christmas extravaganza.

By way of background, one of my all-time favorite films is Peckinpah’s 1969 Western The Wild Bunch, which is set during the Mexican Revolution, probably in 1914.

Also, and I would have thought, utterly separately, I have recently been doing a lot of work on a strange gospel that first appeared in the early seventeenth century called the Gospel of Barnabas. This is a subversive retelling of the story of Jesus in which he proclaims a strongly Muslim message, prophesying the coming of Muhammad as the last prophet. Very probably, it was written by the Spanish Muslims who had been forced to convert to Christianity, the Moriscos, and who were eventually expelled from the kingdom in 1614. Some Morisco, at least, got his revenge by writing Barnabas, which currently enjoys vast popularity in the Muslim world as a counterblast to Christian claims. I have a lengthy book chapter on Barnabas coming out in 2021.

So why on earth am I linking those two phenomena, the film and the gospel?

La Golondrina

The link is a song, the beloved Mexican song of departure, exile, and farewell, La Golondrina, which is often today heard at funerals. It is sung heartbreakingly during The Wild Bunch, and is also heard over the final titles:

A donde ira

Veloz y fatigada

La golondrina

Que de aquí se va

Por si en el viento

Se hallara extraviada

Buscando abrigo

Y no lo encontrara

Where can it go

rushed and fatigued

the swallow

passing by

tossed by the wind

looking so lost

with nowhere to hide.

The song’s origins are a little mysterious, if not quite as weird as Barnabas itself. I quote Wikipedia:

“La Golondrina” (English: “The Swallow”) is a song written in 1862 by Mexican physician Narciso Serradell Sevilla (1843-1910), who at the time was exiled to France due to the French intervention in Mexico. The lyrics come from a poem written in Arabic by the last Abencerrages king of Granada, Aben Humeya, in a translation by Niceto de Zamacois, which Sevilla found in a magazine used as packing material.

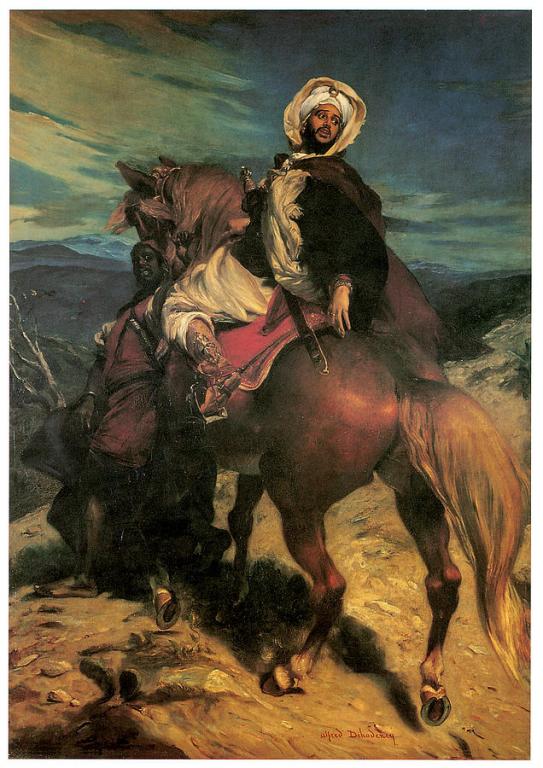

This demands some explanation. The fall of Muslim Spain was a multiple stage process, and two key events are often confused. In 1492, the Christian kings annexed the Emirate of Granada, the last Muslim state in the peninsular, and expelled its king, whom the Spanish knew as Boabdil. Most of the Muslims accepted notional Christian conversion, becoming the Moriscos, but that conversion was for most a superficial affair. In 1568, the Moriscos rebelled under the Aben Humeya mentioned here, who was killed the following year. All these events attracted deep romantic interest in the nineteenth century, especially in the 1860s, and the two figures – Boabdil and Aben Humeya – were often confused as the “last king of Granada.” At various points, each of the two was given credit for composing the Golondrina.

Marià Fortuny, The Slaying of the Abencerrajes (1870)

Now, Serradell’s authorship is undoubted, but the issue is whether he was actually drawing on an older text, and much ink has been spilled over that. You can find an astonishingly detailed history of the song here. Almost certainly, there was not in fact an Arabic original, and that story was part of the common romanticization of the time. The Abencerrages dynasty was the subject of much writing in the nineteenth century, by Washington Irving and others, and it is hardly surprising that a Mexican author in the 1860s would latch on to the legend. But the core fact here is that the song was commonly assumed to be about the Muslims being exiled from Spain, which is my Barnabas link.

Old Mortality

So where did Peckinpah find the song? He spent a lot of time in Mexico, and could have heard it in many places, but here is my discovery. I was recently re-reading Katherine Anne Porter’s classic 1939 collection of three novellas published under the title of Pale Horse, Pale Rider. That was also the title of one of the three stories, which concerns the influenza epidemic of 1918, and on which I have posted at this site. The other two stories were Old Mortality and Noon Wine.

The least known of the three, sadly, is Old Mortality, which concerns the stories (true or false) by which families live, and how these over time become myths that determine the attitudes of later generations. It also centrally concerns generational conflict. The story has an interesting scene at a fancy dress ball, set in Texas at the end of the nineteenth century. That ball is pivotal to the whole narrative:

Harry and Mariana, in conventional disguise of romance, irreproachably betrothed, safe in their happiness, were waltzing slowly to their favorite song, the melancholy farewell of the Moorish King on leaving Granada. They sang in whispers to each other, in their uncertain Spanish, a song of love and parting and that sword’s point of grief that makes the heart tender towards all other lost and disinherited creatures: Oh, mansion of love, my earthly paradise. . . that I shall see no more. . . whither flies the poor swallow, weary and homeless, seeking for shelter where no shelter is? I too am far from home without the power to fly. . . . Come to my heart, sweet bird, beloved pilgrim, build your nest near my bed, let me listen to your song, and weep for my lost land of joy. . . .

Beyond doubt, that is the Golondrina, although it is not named as such, and Porter’s description seems to attribute it to Boabdil, the last king of the older realm of Granada, expelled in 1492. Boabdil (Muhammad XII) was a tragic hero in nineteenth century romantic art and literature, whose “Last Sigh” on departing was much commemorated. (Salman Rushdie took the phrase as the title for his 1995 novel The Moor’s Last Sigh). The supposed location of that sigh – Puerto Del Suspiro del Moro – is a notable mountain pass, and a tourist attraction.

Alfred Dehodencq, Boabdil el Chico (1869)

Note Porter’s “melancholy farewell of the Moorish king,” which perfectly fits Boabdil. As I said, Aben Humeya is normally credited as author, but Porter is absolutely not alone in any confusion on this point.

When Porter was writing in the 1930s, the Golondrina was not well known in Anglo America, and I personally don’t know many early written references to it. But Porter herself knew Mexico very well indeed and was closely associated with Mexican radicals and leftists in the 1920s. A sociable woman, she had probably married a couple of them. (As she declared in her own defense, “I have no hidden marriages. They just sort of escape my mind.”)

Peckinpah and Porter

So what is the Peckinpah link? I’m glad you asked. In 1965, Peckinpah’s career was in meltdown, having had desperate struggles with the studio over his film Major Dundee. He had undoubtedly heard the classic words “You’ll never work in this town again!” Unable to make movies, what he did instead, in 1966, was to write and direct a stunning television production for ABC’s Stage 67, which was so excellent that it restored his career and reputation. Many people still regard his work in this television piece as a classic, a masterpiece of the medium. Based on that new credibility, Peckinpah went off to make his passion project, which was The Wild Bunch. That appeared in 1969, and it left Western fans around the world singing La Golondrina. Some of us still do.

So what was the television production that restored his reputation? It was Porter’s Noon Wine, one of the three novellas in the 1939 collection, and she herself was very pleased with his script. Indeed, without her strong recommendation, he would never have got the contract. Porter herself was at the top of her reputation in 1966, the year she won a Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. As a Texan with a deep interest in the borderlands and the West, she shared a common sensibility with the Californian Peckinpah. Both The Wild Bunch and Old Mortality begin in south Texas. In the latter book, not long after the dance scene I quoted earlier, Harry flees to Mexico to escape scandal and potentially lethal violence.

Peckinpah was a literate soul. In order to do his adaptation, he obviously read Noon Wine, the middle story in the collection. It is surely safe to assume that he also read the first piece, which is Old Mortality, with that lovely passage about the Golondrina. I think that is where he got the idea for the song, and how to use it in the film. Given the topics he was obsessed with throughout his career – death, nostalgia, the passing of an old world – how could he have resisted a title like Old Mortality? That would not have been a bad alternate title for The Wild Bunch itself. More to the point, his film addresses so many of the same themes that are central to Old Mortality, such as shifting values, and the legends by which people live and die. Not to mention fleeing to a more authentic West in Mexico.

Porter had a deep interest in film-making, dating back at least to the 1920s. Surely, Peckinpah must have read her 1934 story Hacienda, which is about making a major film in Mexico, and specifically about searching for locations. This grew out of her work with Sergei Eisenstein and his Soviet associates, as they strove to make Que Viva Mexico! Especially in his editing techniques, Eisenstein was a mighty influence on Peckinpah. Sentences like the following from Hacienda must have resonated powerfully with Peckinpah: “The camera had caught and fixed in moments of violence and senseless excitement, of cruel living and tortured death, the almost ecstatic death-expectancy which is in the air of Mexico.” Does that not sound like a foreshadowing of The Wild Bunch? Porter and Peckinpah really would have had a lot to talk about.

A Tribute?

Was the use of La Golondrina in the film an explicit nod to Porter? Without her Noon Wine, there would have been no Wild Bunch. The film is full of other tributes and nods to iconic figures. The final scenes borrow visually from Treasure of the Sierra Madre: that’s why the Wild Bunch riders at that point unaccountably decide to don their hats under the Mexican sun. Musically, the film’s other best known song is the hymn Shall We Gather At The River, which was an instantly recognizable trademark of John Ford. It appears in seven of Ford’s films. (That hymn dates from 1864, Golondrina from 1862). Its use in The Wild Bunch can’t be understood except as a Ford hommage. So why should Peckinpah not salute his fellow Western free spirit, Mrs. Porter?

I think I am the first person to make the Old Mortality connection: do correct me if I am wrong.

It does all make me wonder what other strange linkages I might encounter between fields of interest that on the surface have nothing whatever to do with each other.

Last year, I had the great pleasure of reading W. K. Stratton’s wonderful book The Wild Bunch: Sam Peckinpah, a Revolution in Hollywood, and the Making of a Legendary Film (Bloomsbury 2019). Jerry Holt has a chapter on “La Golondrina: The Secret Text of The Wild Bunch,” in Michael Bliss, ed., A Uniquely American Epic: Intimacy and Action, Tenderness and Violence in Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (University Press of Kentucky, 2019). An excellent older read is Thomas F. Walsh, Katherine Anne Porter and Mexico: The Illusion of Eden (University of Texas, 1992). You could easily use that subtitle for a book on Peckinpah’s Mexico.