2004 was my first experience of a presidential election on an evangelical college campus. For the most part, I don’t remember that contest inspiring a great deal of passion at Bethel — certainly nothing to compare with what I’d seen four years earlier on the Yale campus. Every morning I walked past a decent number of Bush bumper stickers in the parking lot… and none (that I recall) for Kerry. But there was at least one car decorated like this:

It belonged to my colleague, friend, and mentor G.W. Carlson, a political scientist and Russian historian who served on our faculty for over forty years. He died of a stroke five years ago this month, so he’s come to my mind often of late. But the other reason I thought of his “God is not a Republican… or a Democrat” bumper sticker is that a much more famous Baptist sent out the following tweet last week:

Jesus is not a Republican or a Democrat.

— Beth Moore (@BethMooreLPM) February 3, 2021

It’s not just Beth Moore. Last month Zachary Wagner, editorial director of the Center for Pastor Theologians, wrote a pre-Inauguration Day post that started:

Jesus is not a Republican. This has been said before. But now it must be said more loudly and more clearly than ever. There are good and godly men and women who vote Republican and serve in elected office as Republicans. But the association of the name of Christ with the Republican party of Trump has become a scourge of shame for the church. The time has come––indeed, it is long overdue––for the entire church to denounce this association in the strongest possible terms.

It’s not just Americans. Last summer British evangelical Adrian Warnock wrote a “Jesus is not a republican or a democrat” post here at Patheos. “For the sake of the global cause of Christ,” he pleaded with American evangelicals, “PLEASE do not claim that Christians can only follow one political tribe.”

So what’s the history of this expression? It goes back at least as far as a Clinton-era book by Tony Campolo. Is Jesus a Democrat or a Republican? (1995) took its title from its first chapter, in which Campolo argued that

So what’s the history of this expression? It goes back at least as far as a Clinton-era book by Tony Campolo. Is Jesus a Democrat or a Republican? (1995) took its title from its first chapter, in which Campolo argued that

God expects us to never let partisan loyalty tempt us into reading the platform ideas of any party into the Bible. If we are to be faithful to the true God, we must not allow the principles of any party to override what the Bible has to say to us.

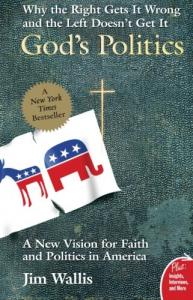

In 2004, the progressive evangelical group Sojourners printed the “God is not a Republican… or a Democrat” bumper sticker that GW affixed to his car. Two years later, in the preface to his book, God’s Politics: Why the Right Gets It Wrong and the Left Doesn’t Get It, Sojourners founder Jim Wallis reiterated that

God is not partisan; God is not a Republican or a Democrat. When either party tries to politicize God, or co-opt religious commitments for their political agendas, they make a terrible mistake. The best contribution of religion is precisely not to be ideologically predictable nor loyally partisan. Both parties, and the nation, must let the prophetic voice of religion be heard. Faith must be free to challenge both right and left from a consistent moral ground.

At the time, I remember wondering if evangelicalism had turned a page, if it might cease to be viewed as something other than the Republican Party at prayer. In October 2006, Wallis came to Bethel for an evening conversation with theologian Greg Boyd that filled our Great Hall and was covered by CNN. A few weeks later former Bush adviser David Kuo called for evangelicals to fast from politics, in part to help create some space between themselves and the GOP. In 2007 a University of Nebraska freshman named Jake Meador looked forward to a talk by historian Randall Balmer, who had had his own “Jesus Is Not a Republican” essay appear in the Chronicle of Higher Education. Meador (a conservative Presbyterian who now edits Mere Orthodoxy) observed that Balmer, Wallis, and Campolo were all “trying to make [the point] that Christianity is not about a political ideology; Jesus is not a Republican or a Democrat. Jesus, and the life he modeled and demands of his followers, transcends partisan politics.”

But on the eve of the 2012 election, Wallis and Wes Granberg-Michaelson took to The Huffington Post to reiterate that “God Is Still Not a Republican, Or a Democrat.” Lamenting the enduring strength of the Religious Right, they again decried how “a few conservative evangelical leaders have allowed their political ideology to trump fidelity to the whole witness of the Bible….”

And here we are, two presidencies later, with not just Beth Moore but former congressman Trey Gowdy repeating the mantra that Jesus is “not a Republican or a Democrat.”

A GOP politician and lawyer from South Carolina, Gowdy was talking to Fox News last June, after Donald Trump’s infamous church photo op during the George Floyd protests in Washington. But more often, the “Jesus is not” slogan has been tied to politically progressive evangelicals. Writing in 2012 at his own blog, our own David Swartz interpreted Wallis and Michaelson’s use of the slogan as a reflection of “the politically homeless nature of the evangelical left…” But other evangelicals had wondered if the members of that “moral minority” really meant the “or a Democrat” part of the phrase. Following up on the 2006 event at Bethel, Greg Boyd credited Wallis with trying

hard to remain non-partisan, repeating over and over that “God is neither Democrat nor Republican.” But he nevertheless ends up with a set of (mostly democratic sounding) opinions that he believes does in fact constitute “God’s Politics” (the name of his book). Unfortunately, the minute we attach a “God” or “Christian” label to one set of political opinions, we legitimize others attaching the label “God” or “Christian” to their set of political opinions.

Campolo himself addressed the problem in a 2005 interview with NBC News. Reiterating that “it’s time for us to stand up and say Jesus is not a Republican; Jesus is not a Democrat,” he emphasized that “the answer to the religious right is not to create a religious left in which we get a bunch of Christians who are saying if you don’t vote Democratic, you’re out of the will of God.” (In his 1995 book, he had observed that those attending mainline Protestant churches in the 1960s “could easily come away believing that Jesus was a Democrat.)

While David acknowledged nine years ago that Wallis and Michaelson were closely tied to the Democratic Party, he nevertheless suggested “that each feels a deep ambivalence about voting for a pro-choice president who continues to bomb with drones.” I know I did, much as I admired that particular president.

So how do we proceed? Gowdy’s surely right that Christians would “all be better off if we follow the teachings of Christ and did not involve him in partisan politics.” But though Jesus belongs to no political party, following him necessarily has implications for how we participate in a politically polarized society. God was not partisan or ideological, wrote Wallis, but he did have a “politics,” one that

So how do we proceed? Gowdy’s surely right that Christians would “all be better off if we follow the teachings of Christ and did not involve him in partisan politics.” But though Jesus belongs to no political party, following him necessarily has implications for how we participate in a politically polarized society. God was not partisan or ideological, wrote Wallis, but he did have a “politics,” one that

reminds us of the people our politics always neglects—the poor, the vulnerable, the left behind… challenges narrow national, ethnic, economic, or cultural self-interest… reminds us of the creation itself… pleads with us to resolve the inevitable conflicts among us, as much as is possible, without the terrible cost and consequence of war. God’s politics always reminds us of the ancient prophetic prescription to ‘choose life, so that you and your children may live,’ and challenges all the selective moralities that would choose one set of lives and issues over another.

I have no regrets about voting for Democrats in 2016 and 2020; it was the best option available to protect this democracy from Donald Trump. But perhaps the Biden presidency is a good time for Christians to step back and think in fresh ways about how we can participate in “God’s politics” more than human partisanship.