Hunter Hampton is Assistant Professor of History at Stephen F. Austin State University. Hunter earned his Ph.D. at the University of Missouri in 2017, and he’s at work on his first book, Man Up: College Football and the Making of American Religion. In the wake of last Sunday’s big game, he narrates the football genealogy that connects two members of the Kansas City Chiefs to the “Mormon Father of Modern Football.”

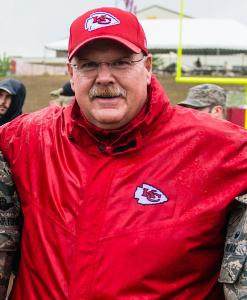

On Sunday night, the Tampa Bay Buccaneers shocked the Kansas City Chiefs. Before the game, Las Vegas oddsmakers favored the Chiefs by three points. With the creativity of coach Andy Reid and passing skills of quarterback Patrick Mahomes II, the majority of sportswriters picked Kansas City. But Tom Brady, who seems to have struck a deal with a spiritual force (which one is uncertain), again proved his doubters wrong. While this may have temporarily stalled Kansas City’s dynasty dreams, Las Vegas has already selected them as Super Bowl favorites for next season. They believe in the magical connection between Reid and Mahomes.

On the surface, the two have little in common. Reid is a sixty-two-year-old, white coach that graduated from Brigham Young University which is known for its Mormon honor code. Mahomes is a twenty-five-year-old black quarterback from East Texas who attended Texas Tech which is known for cold-beer and dust storms. However, a genealogical study into these men’s past, a tool important to both Mormons and football fans, reveals a common source. The football family trees of Reid and Mahomes trace back to a Mormon’s Mormon that coached at BYU for thirty-eight years and fathered modern football: LaVell Edwards.

Reuben LaVell Edwards was born into a Latter-day Saint family just north of Provo, Utah. As the eighth of fourteen children, he was baptized into the Church when he was eight and grew up attending BYU Cougar football games. The Latter-day Saints wrestled with the virtues of the violent game at the turn of the twentieth century. In 1899, the Church’s General Board of Education and future President of the Church, Joseph F. Smith, banned football at LDS schools. BYU went over two decades without a team. In 1919, BYU successfully petitioned to reinstate football after World War I exposed the need for football to train Mormon men. As a child, Edwards witnessed the school and Church’s commitment to football as a tool for assimilating into mainstream American culture. After a successful football career of his own at Utah State, he was hired by BYU as an assistant coach in 1962. Edwards took the helm of the BYU football team ten years later.

As the head coach at BYU, Edwards brought a new style of football. Instead of running the ball, he

passed the ball on any down, at any point of the game, with any amount of time left on the clock. Though the forward pass had been a legal part of the game for sixty-six years, a strong running game still defined success in football. Passing the ball was too uncertain. Edwards bucked this belief to chart his own path built on his quarterback. In his second season, BYU’s quarterbacks averaged twice the number of pass attempts per season, thirty-six, as his predecessor’s. Edwards’s offense reached its potential in 1976 by finishing eighth in the country in points scored per game. For nine of the next eleven years, BYU finished in the top ten of scoring. During this stretch of offensive success, Edwards recruited a massive offensive lineman from Southern California who would play, and eventually coach, under him: Andy Reid.

Edwards’s success on the football field and commitment to his faith gave him a special standing in the Church. In 1976, Edwards gave a talk at BYU entitled “Keys to Spiritual Growth – A Game Plan for Life.” He identified the four keys to a spiritual person as self-control, setting goals, serving others, and receiving the Holy Spirit. The speech concluded with the retelling of a story about a non-LDS player he recruited to BYU who struggled his freshman season but committed himself to the first three keys to growth. As a result of his control, goals, and service, the player made the winning play in the spring football game to cement his spot as a starter the following season. He told Edwards this was the happiest moment of his life and that he was getting baptized into the Church the next day in front of his family. Throughout his career, Edwards seamlessly wove together personal spiritual development, family values, and BYU football’s ability to spread the faith.

In the years after BYU’s undefeated 1984 season, Edwards continued to churn out successful players. Jim McMahon was a two-time All American at BYU and two-time Super Bowl Champion. Steve Young was an All-American and Heisman trophy runner-up at BYU; he then gained notoriety by winning three Super Bowls. In his 1994 MVP season, he averaged twenty-eight passes per game, eleven fewer than during his final year at BYU under Edwards over a decade prior. In 1990, Ty Detmer finished the season with 562 pass attempts for 5,188 yards, becoming BYU’s first and only Heisman Trophy winner.

After earning the reputation of “Quarterback U,” coaches from across the country flocked to Provo to study Edward’s offensive scheme. In 1987, Edwards’s staff invited Hal Mumme after his UTEP offense had employed BYU’s system to upset them two seasons prior. Mumme made annual spring visits to learn under Edwards. In 1989, Mumme invited Mike Leach to join him. Leach was a long-winded BYU graduate who had studied Edwards’s pass-heavy offense from the stands as a student before going off to law school at Pepperdine. Through a series of twists and turns that could only have happened to Leach, including coaching gigs at Iowa Wesleyan and in Finland, he landed his first head coaching job at Texas Tech in 2000. The year before Leach arrived, Tech quarterbacks threw the ball 268 times the entire season. In Leach’s first season, his sophomore quarterback, Kliff Kingsburry, threw the ball 585 times. Kingsbury took over the head coaching position at Texas Tech in 2013. His teams continued to pass the ball at a dizzying rate that peaked in 2016 when his gun-slinger quarterback threw 591 passes. That quarterback was Patrick Mahomes.

In the same year that LaVell Edwards took over as head coach at BYU, football became America’s favorite spectator sport. For the past fifty years, the BYU football team has been a beacon of Mormonism. Family genealogy provides Mormons the opportunity to identify past family members to be brought into the faith through the practice of Baptism for the Dead. Coaching genealogy illustrates to football fans the transfer of schemes and philosophies from one team to the next. While the connection between Andy Reid and Patrick Mahomes may not be familial, they have deep roots that have helped them dominate the modern NFL. They are both branches of a coaching tree whose trunk is LaVell Edwards.