“Off to preach?”, my most Baptist colleague used to ask my most Reformed colleague. “No,” she replied, “to teach.”

That exchange has often come to mind as I’ve followed a lawsuit pitting social work professor Margaret DeWeese-Boyd against her former employer, Gordon College. At the heart of the case is the question of whether Christian college professors are also Christian ministers.

An evangelical institution outside Boston, Gordon denied DeWeese-Boyd’s application for promotion to full professor in 2017, even though she had the backing of her department and faculty senate. Alleging that the administration was punishing her for opposing Gordon’s traditional stance on sexuality, DeWeese-Boyd went to court, contending that she had been discriminated against.

Gordon’s attorneys have claimed that promotion was denied because DeWeese-Boyd failed to meet criteria for scholarship, but they also invoked what’s called the “ministerial exception” to antidiscrimination laws. As I understand it, that principle was formalized in 2012, when the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously dismissed a lawsuit filed by Cheryl Perich, a teacher fired by Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church and School. Both the free exercise and establishment clauses of the First Amendment, wrote Chief Justice John Roberts, left to religious groups the employment of their ministers, and Perich qualified as a “minister” on several counts. (Last year, a 7-2 SCOTUS majority reaffirmed that principle in a case involving a teacher at Our Lady of Guadalupe School, a Catholic institution in California.)

Likewise, Gordon president Michael Lindsay has argued that Gordon professors function as ministers, even if they aren’t ordained clergy or don’t teach subjects like theology, biblical studies, or religion. DeWeese-Boyd and her colleagues not only have to “profess the Christian faith” themselves, but are expected “to assist students in their spiritual journey as part of their intellectual formation; to be available to minister to students with questions, personal needs, spiritual exploration” and “to inculcate the Christian identity and transmit it to the next generation.” (I’m quoting here from Daniel Silliman’s excellent summary of the case at Christianity Today.)

Earlier this month, Massachusetts’ Supreme Judicial Court upheld the trial court’s ruling in favor of Schwab’s client. (Here’s Silliman’s report on that result.) “While it may be true that Gordon employs Christians, and ‘Christians have an undeniable call to minister to others,’” concluded Justice Scott Kafker, “this line of argument appears to oversimplify the Supreme Court test, suggesting that all Christians teaching at all Christian schools and colleges are necessarily ministers.” He and his colleagues seem to have been persuaded by DeWeese-Boyd’s attorney, Hillary Schwab, who contended that her client’s functions on campus weren’t “religious or ministerial,” since she didn’t teach religion, lead chapel or preach at it, conduct Bible studies, etc. “The ministerial exemption is not boundless,” argued Schwab, since otherwise religious employers would have “carte blanche to violate the anti-discrimination laws.”

It’s unclear if Gordon will appeal this month’s decision, but it wouldn’t surprise me to see it continue to a higher court. One way or another, this case has important implications for Christian universities like my employer, which joined an amicus brief filed by the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities in support of Gordon. If the DeWeese-Boyd judgment were affirmed, warned the CCCU, “it would pose an existential threat to religious higher education in Massachusetts.”

I’m no legal scholar, so I won’t pretend to assess how well the Massachusetts court employed the Hosanna-Tabor criteria for the ministerial exception, or to predict if its ruling will become a new test for the Our Lady decision. Instead, I want to think about the larger question of whether Christian college professors like me are “ministers.” I’ve probably done enough to meet the Tabor criteria (e.g., I preached in chapel in 2019, led a short-lived Bible study when I first came to Bethel, and have led students in prayer at one time or another in all of my classes), but I want to think of “minister” less in the context of legal precedent than the historical and religious context of Christian higher education.

(And I do mean “think”… I’ve been in my job for eighteen years, and I don’t have a settled opinion on this matter. What follows is a rather lengthy example of me using blogging to “think in public.”)

My first, most instinctively Protestant instinct is to say, “Of course I’m a Christian minister: all Christians are ministers.” (Asterisks in the bulletin at my parents’ Southern Baptist church used to mark the moments during worship when “All the ministers will stand.”) With my Pietist forebear Philipp Spener, I want to decry the notion that non-clergy are excluded from “spiritual functions… as if it were not proper for laymen diligently to study in the Word of the Lord, much less to instruct, admonish, chastise, and comfort their neighbors, or to do privately what pertains to the ministry publicly, inasmuch as all these things were supposed to belong only to the office of the minister.”

But even Spener would maintain the distinctness of that office, and argue that certain spiritual functions are reserved to those specially called and gifted members of the common priesthood that Protestants call ministers or pastors. I doubt he’d see someone like me as fulfilling that kind of role.

Even when I’ve used part of his 1675 book quoted above (Pia Desideria) to help flesh out a Pietist vision for Christian higher education, I’ve had to acknowledge that what little Spener writes about education is specifically intended for the training of professional ministers. When he calls the pastor-preparing departments of 17th century universities “workshops of the Holy Spirit,” where “study without piety is worthless,” I seek to extrapolate such principles to present-day Christian liberal arts colleges where only a tiny handful of students are preparing for seminary, or even majoring in programs like ours in Missional Ministry. I’m a devout Christian working at an explicitly “Christ-centered” university… but as a historian who primarily teaches European and military/diplomatic history to students who are preparing for seemingly secular professions. And unlike many of the first generations of faculty at church-related schools like Bethel, I was trained entirely within the secular academy and credentialed according to its standards.

Nonetheless, there’s a reason that a University of Minnesota-trained Russian historian like my Baptist colleague could use the words “preach” and “teach” interchangeably — while my Calvin College-educated colleague (a historian of prostitution) would as firmly reject that equivalence.

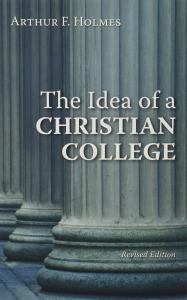

The tension shows up in the very first book I was given when I had to figure out what it meant to be a history professor at a place like Bethel. “The teacher is the key to a climate of learning,” observed Wheaton philosophy professor Arthur Holmes. “His teaching is his ministry” (emphasis mine).

I don’t think that’s an unusual sentiment in Christian colleges. (Or Christian schools like the one that fired Cheryl Perich: “God is leading me to serve in the teaching ministry,” she wrote after her termination — a sentence quoted by John Roberts in the Hosanna-Tabor opinion). I’ve used much the same language myself, to explain my sense of calling to students, colleagues, and readers. I sometimes ruminate on the pastoral dimensions of being a professor at a personal blog I named after an essay about the 18th century pastor and educator August Hermann Francke, a “Pietist schoolman” who “tended to place less emphasis… on erudition than on pastoral care, less on the authority than on the responsibility of the pastoral office.”

So I’d agree that I’m engaging in two of the “ministerial” roles that Lindsay ascribed to Gordon professors: “to assist students in their spiritual journey as part of their intellectual formation; to be available to minister to students with questions, personal needs, spiritual exploration…” I suspect that DeWeese-Boyd did the same for her students.

It’s the third that gives me pause and seems to be in question in DeWeese-Boyd’s case: “to inculcate the Christian identity and transmit it to the next generation.”

Writing for the majority in Our Lady, Justice Samuel Alito argued that Hosanna-Tabor recognized that “inculcating its teachings” was “at the very core of the mission of a private religious school.” In his Tabor concurrence, Alito had reasoned that religious authorities had to be free to hire their leaders and their employees who facilitated worship and other rituals, but also “those who are entrusted with teaching and conveying the tenets of the faith to the next generation.”

I can see the argument in the context of churches themselves, perhaps even in K-12 schools. But is my task as a Christian college history professor to “inculcate” Christianity in my students, “conveying the tenets of the faith” to them?

Here I’m struck that I could only find the word “pastor” in Holmes’ Idea of a Christian College twice, both instances suggesting that “ministers” like me engage in something unlike catechesis. As Christian college professors, he wrote, we must instead counter the

defensive mentality… still common among pastors and parents… that the Christian college exists to protect young people against sin and heresy in other institutions. The idea therefore is not so much to educate as to indoctrinate, to provide a safe environment plus all the answers to all the problems posed by all the critics of orthodoxy and virtue.

Teaching may be my ministry, but my flock are Christian students who “are often raised on credulity, sometimes told it is dangerous to think and to question what they are taught.” My task is less to supply answers than to ask questions, of students whose faith may consist primarily of what Holmes called “a response to the stimuli of parents and pastors.”

I teach, Holmes would tell me, but I do not indoctrinate — even those theological or ethical beliefs that I personally affirm. Indeed, sometimes my role requires me to teach contradictory doctrines. Last week, for example, I spent a fair amount of time in our Christianity and Western Culture survey making the best case I could for medieval theologies of transubstantiation and penance — beliefs that I don’t share; beliefs that Bethel’s Baptist founders would have rejected as heresies.

Why? Because, as I was told in my job interview, Bethel exists to help students “make their faith their own.” Not their parents’ or their pastors’, not Bethel’s or mine. Their own.

That doesn’t mean I’m at Bethel to talk students out of beliefs that I affirm. But “making faith their own” is only meaningful to me because it’s possible that my students will come to disagree with me about doctrines that are indisputably central to Christianity. I hope and pray that my students choose to follow Jesus Christ, but the experience of studying war and genocide with me may leave them convinced that I’m right about God’s apparent absence but wrong about his Son’s presence. It’s painful to contemplate, but my teaching ministry might help a few students to make their non-faith their own.

I’ll certainly try to complicate their doubt, just as I’m complicating the faith of their classmates. But can I really be said to be inculcating Christian teachings about matters as crucial as the existence and nature of God — let alone something as secondary as sexuality?

I don’t think so, but then I’m a Christian minister who teaches, not preaches.