Given the Easter weekend off from teaching, I spent last Friday searching for a place to get my first COVID vaccination. I found one… three hours from home, in Minnesota’s Iron Range. So to keep me company on my journey north, I checked out an audio book about a much longer, more arduous trip in the same direction: Hampton Sides’ In the Kingdom of Ice, an engrossing account of the ill-fated Arctic voyage of the U.S.S. Jeannette. While Christianity plays little role in his story, Sides’ book reminded me that, for some Westerners in the late 19th century, science was akin to religion — as capable as any traditional faith of inspiring fervent belief, even to the point of martyrdom.

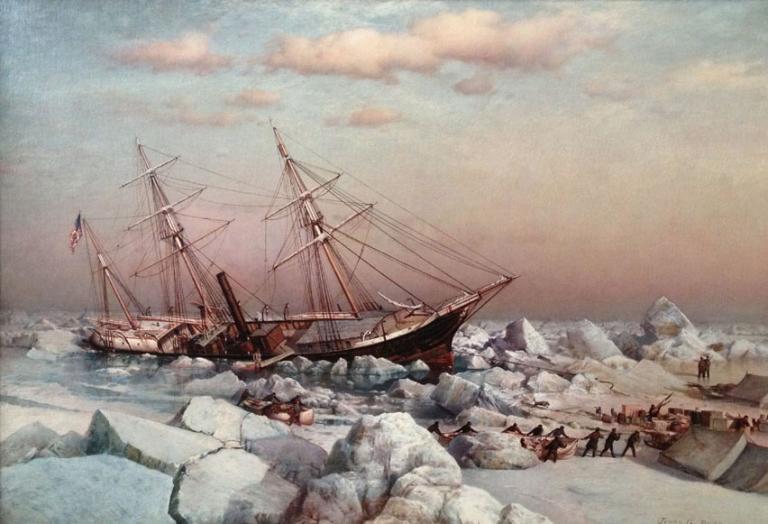

The captain of the Jeannette was an ambitious American naval officer named George Washington De Long. With the backing of New York Herald publisher James Gordon Bennett Jr., De Long purchased (and renamed) the Pandora, a British vessel with extensive Arctic experience, and began retrofitting and provisioning it for a multi-year expedition to the North Pole. But in September 1879, just two months after departing San Francisco, the Jeannette’s crew of thirty-three found themselves trapped by ice in the Chukchi Sea. They remained there for the better part of two years, finally abandoning ship as the vessel was crushed in June 1881. Setting off across the ice in hopes of reaching Siberia, only one group of thirteen survived. De Long starved to death at the end of October, though his journals were discovered, to be edited and published by his wife.

“He belonged to the men who have cared for great things,” Emma De Long wrote of her husband, “and he entered upon the work before him with a single-minded earnestness, and a brave trust in God.” To him, she insisted in a somewhat defensive footnote, “God was no vindictive, stern tyrant. The records sufficiently witness to his devout, unswerving confidence in a watchful Father.” Perhaps such traditional convictions did sustain George De Long through his terrible last months, but it was more modern faiths that animated his and other attempts to reach the North Pole.

First, the Enlightenment’s belief in human potential and goodness. “The Arctic Ocean has been for years the nursery of heroic deeds,” wrote Congregational pastor W. L. Gage, introducing the survivor’s memoir by the Jeannette’s naturalist, Raymond Lee Newcomb, with such exploration revealing “that which is noblest and most admirable in man….” Unlike war, in which courage was alloyed with cruelty, Arctic expeditions like De Long’s revealed “one continuous strain of heroism, one incessant and good-humored story of that which is best and most hopeful in the human soul.”

Though Gage likened “stories of polar adventure” to the “glorious recklessness” of fictional characters like Tom Sawyer, De Long thought himself cautious, diligent, and rational. He attempted his expedition precisely because he believed it was backed by the other faith of modernity: science.

De Long experienced what Sides calls his “baptism by ice” in 1873, while taking part in the attempted rescue of the doomed (and likely murdered) Arctic explorer Charles Francis Hall. In Sides’ telling, Hall had been driven by an “almost religious fervor” for a scientific theory that was as popular as it was wrong:

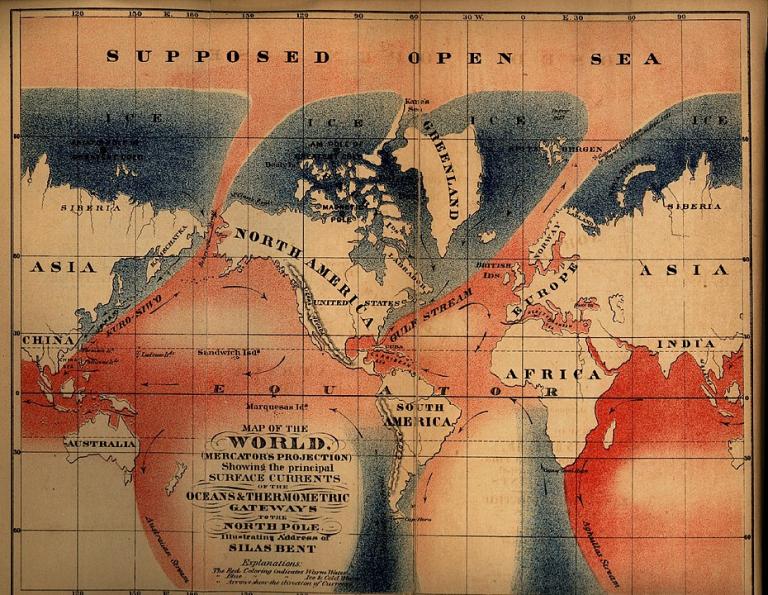

The idea, widely believed by the world’s leading scientists and geographers, went like this: The weather wasn’t especially cold at the North Pole, at least not in summer. On the contrary, the dome of the world was covered in a shallow, warm, ice-free sea whose waters could be smoothly sailed, much as one might sail across the Caribbean or the Mediterranean. This tepid Arctic basin teemed with marine life—and was, quite possibly, home to a lost civilization. Cartographers were so sure of its existence that they routinely depicted it on their maps, often labeling the top of the globe, matter-of-factly, OPEN POLAR SEA.

Why would anyone think this? We don’t need to delve deeply into explanations that struck Sides as acts of “desperation… like trying to prove the existence of God by employing elaborate teleological arguments.” What’s most striking is that world-respected scientists, for decades, “had contributed to the plausibility, the probability, and finally the certainty of this chimerical idea.”

While the tragic results of British expeditions like Sir John Franklin’s had fostered skepticism about the theory among members of the Royal Geographical Society, the Open Polar Sea had significant support from leading geographers, cartographers, and oceanographers on both sides of the Atlantic. Sides particularly emphasizes the writings of the American naval officer Silas Bent and the German polymath August Petermann. Both men believed that warm-water currents like the Atlantic’s Gulf Stream and the Pacific’s Kuroshio could help a steam-powered ship break through the ring of ice along the Arctic Circle, after which it would find relatively smooth sailing to the Pole itself. While earlier explorers like Franklin and Hall had tried the dangerous passages to either side of Greenland, Bent and Petermann urged a Pacific route through the Bering Strait, which separated Russia from the territory it had recently sold to the United States. Bent told a St. Louis crowd in 1868 that his theory may, “in God’s Providence, be the means of averting the recurrence of some of the sad calamities that have attended former expeditions….”

In his 1869 book on The Open Polar Sea, Isaac Israel Hayes described the iceberg-ridden waters off Greenland as “a land of enchantment… the ‘very seat of the gods.’” He likened the High Arctic to sites from Norse mythology: Valhalla, Gimle, and Himinborg, “the Celestial Mount, where the bridge of the gods touches Heaven.” But while they held their beliefs as devoutly as any pre-modern, adherents generally expressed their convictions in the language of scientific method, not myth. One magazine reassured readers of his article that Bent’s notion of a “Thermometric Gateway to the Pole” rested on “deductions of science” and “the quiet authority of mathematical calculation.” All that was missing was an explorer willing to test the hypothesis with his life. “Perhaps I am wrong,” Petermann told a reporter from the Herald, “but the way to show that is to give me the evidence.”

Indeed, the deaths of the Jeannette‘s crew provided that evidence. But it didn’t take nearly that long for George W. De Long to rethink his faith in the Open Polar Sea. By June 1880, a year before he finally abandoned ship, the stranded explorer came to the bitter realization that that Bent’s “thermometric gateway” was both “a delusion and a snare.”