One sunny afternoon in Germany, I found myself in need of a restroom. And I realized that historian and philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn was on to something.

I was in Berlin for a conference, which I then extended into a European vacation with my friend Jill. By “European,” I mostly mean Berlin. It contains more than enough to hold your interest for a week. But we are Americans, so Europe means castles. We went in search of the closest one.

Turns out the monarchs of Prussia didn’t sequentially inhabit a Prussian king’s castle like normal aristocrats. They each built their own castle. But they had the decency to do it all in one place: Potsdam. Which was only an hour by train from Berlin. We signed up for a bus tour.

Monday is the day all German museums are closed, which we hadn’t realized. Fortunately, castles and their grounds are impressive from the outside. Equally fortunately, one of them at least kept the restrooms open.

That castle was Cecilienhof. Built for Crown Prince Wilhelm and named for his wife Cecilie, Cecilienhof copied the English Tudor architecture both admired. Consequently, it didn’t exactly scream “castle” to me.

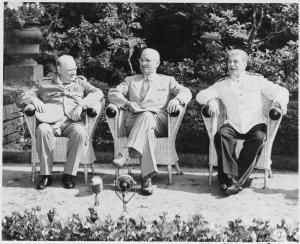

It did scream “I should take a lot of pictures because I can use this in lectures”: Cecilienhof is the location of the famous 1945 Potsdam Conference between Stalin, Churchill, and Truman to determine the shape of geopolitics after World War II.

The Red Army got to the area first and took all the good stuff. (Most things of historical interest are in former East Berlin, for example.) Stalin used this fact to his advantage. Our guide informed us that the Russian leader placed a giant Soviet red star at the entrance to annoy Churchill and made Truman enter by the side door that led to the bathrooms. Our guide then pointed out that the bathrooms are in the same place today and perhaps now might be a good time to use them?

Jill and I had been warned by a friend that public restrooms in Germany require payment. (As did water in restaurants. I’d never been so proud to be an American.) But this bathroom cost more than we thought it would: a full euro each. We had exactly one two-euro coin between us. But you couldn’t just put in the coin and then go through the turnstile. You had to put in the coin, get the ticket that was printed out, collect your change, then scan the ticket, and finally the turnstile would unlock.

This was frustrating enough to figure out if you had the money. The American couple in front of us did not, and we didn’t have extra. They were trying to figure it out and a German woman who was coming out was trying to help. It was chaos. They eventually let us go first while they decided what to do. It was a whole ordeal. We figured it out and Jill scanned her ticket, went through the turnstile, passed back the change, and I repeated the process. Success! We walked through the brief hall into the bathroom.

This bathroom, like all German bathrooms, was spotless. I mean, you’d hope so for the expense. You enter facing the sinks and the stalls are to your left. Weirdly, the toilet seats were square rather than oval. But I got it figured out, actually managed to get out of my stall before Jill exited hers, and went to wash my hands. I was mildly miffed that there was just a roll of paper towels standing on the sink shelf rather than a dispenser (this bathroom cost a dollar!), but it worked.

As I was finishing up, Jill exited her stall, and, discombobulated, turned left instead of right. I saw her out of the corner of my eye and called out, “Oh, don’t go that way. That’s where the urinals are.” She said, “Oh, OK,” turned right instead, and joined me at the sinks. Despite the suboptimal paper towel situation, I successfully dried my hands and exited the bathroom first.

Waiting in the hall, I looked at the door—which was propped open—for the first time. “Jill! Jill!” I yelled. “You’ve got to get out of there! It’s the men’s room!!!”

After we finished laughing hysterically, we debriefed. I had seen the urinals when I exited my stall and thought, “Oh, they must have kept them here because this is a historic bathroom, the one Truman used.” When Jill had seen the urinals, she thought, “Oh, this must be the kind of bathroom where the men’s and women’s sides wrap around and connect.” Neither of us saw the urinals and thought, “Ack! We’re in the men’s room!”

I majored in the history of science as an undergraduate at Princeton, where renowned historian and philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn had taught. That means I read Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions three times. (I really should have skimmed it the second two times it was assigned.)

When I ask normal people if they have heard of the book, they say no. When I ask normal people if they have heard of the phrase “paradigm shift,” they say yes. Kuhn coined that phrase, in that book.

He built this concept off his previous research into the Copernican Revolution. One day in Renaissance Europe, Copernicus up and decided that the sun and planets do not orbit the earth but rather the earth and planets orbit the sun. It’s hard to overstate how radical that was. For one thing, the sun orbiting the earth appeared to have biblical support. For another, it’s what everyone had thought for thousands of years.

So how did he do it? How did he break out of “what everyone knew to be true”? The answer lies in epicycles.

The belief that the sun orbits the earth has the advantage of matching what we see with our eyes. But, technically, it only matches what we see most often and in broadest strokes: the sun rising and setting each day. It doesn’t actually match what we see when we carefully observe the planets, also believed to orbit the earth. The planets don’t traverse across the night sky in accordance with what we would expect if that theory were true.

To account for this fact, ancient astronomers posited “epicycles”: the planets orbited the earth, but they also themselves went around in little circles, like a slinky bent into a ring. This largely made the math work out, but not quite. So astronomers posited additional epicycles within epicycles. Eventually the model and the math were so messy and complicated that a human mind thought, “What if this is just all wrong?” Copernicus underwent a “paradigm shift.”

In other words, the last epicycle was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Copernicus gave in to Occam’s Razor, the philosophical instinct that the simpler explanation is probably the better one. (It actually took Johannes Kepler later positing that the planets did not need to go around the sun in circles, but rather could travel in ellipses, to make the math finally work.)

Part of Kuhn’s insight was that it takes a lot to get to a new paradigm. We are very invested in our ways of seeing the world, and for good reason. Often, there is a perfectly good explanation for the event that doesn’t seem to fit our paradigm within the paradigm itself. It just takes time to find it. So we can’t go willy nilly overthrowing our outlook in the face of every little thing that doesn’t seem to fit it. We’d never get on in life. Our brains are therefore wired to stick to the paradigm.

This is what happened to Jill and me. Once we started using the bathroom, we were understandably very psychologically invested in believing it was the women’s room. When presented with very obvious counter-evidence—urinals—each of our brains automatically invented an “epicycle” to explain their presence. My favorite part of this story is that we invented different epicycles. Because it wasn’t the women’s room, there wasn’t an obvious good explanation that both of our brains would immediately find. We each just unthinkingly made one up that worked for us.

Another big part of Kuhn’s insight was that science at this level is, ironically, more art. Who’s to say whether this piece of apparently contradictory evidence means you should pitch the whole system? Brilliant scientists are the ones who know when and how to do this, and Kuhn claims that it’s these sorts of paradigm shifts that drive science forward.

Kuhn would also note that, strictly speaking, a successful scientific theory is one which allows you to make accurate predictions about the world. It’s not necessarily one that accurately explains how the world works. After all, what is gravity anyway? Why does it work that way? Scientists honestly aren’t sure. But Einstein’s model can both explain more and predict more than Newton’s model. The better theory is the more elegant one with more predictive power. But it too could ultimately be superseded.

Of course, a scientific theory is unlikely to have predictive power unless it in some way corresponds to the real world. But it might be off or incomplete. Or it might be spot on and we’re just missing a key piece of information that explains an apparent anomaly.

As in science, so in life. There’s an art to knowing when to change your mind. To adopt a different religious or political outlook, or not. To change your opinion of a person, for better or for worse. It takes practice, and it takes community. (Peer review exists for a reason!) For Christians, it takes learning to listen to the Holy Spirit. This whole process is part of what the Christian tradition labels “wisdom.” And without wisdom, you just might end up using the men’s room.