As a small tribute to our friend Beth Allison Barr, whose essential new book, The Making of Biblical Womanhood, officially releases today, let me tell a story of evangelical Baptists debating the role of women within the Christian church. Two names will be instantly familiar; most remain unknown.

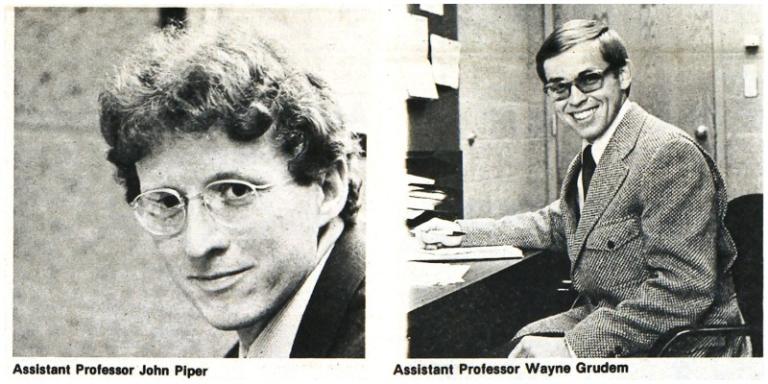

In December 1977, the student newspaper at Bethel College and Seminary (MN) asked Bible faculty, “Should women be ordained pastors of churches?” One fourth-year college professor allowed that “It is a complex hermeneutical question whether Paul’s view was so culturally conditioned that it is not valid today.” But in the end, texts like 1 Tim. 2:12 convinced him that “Paul had a profound insight into the God-given distinctives of male and female. And I think his view which calls for male headship in the home and male authority in the church is a divinely inspired means of preserving the health of the church and the unique glory of man and woman.” Meanwhile, a newcomer to the college faculty gave an even sharper response: “Definitely not. The question here is whether we are going to obey the Bible or conform to the pressures of modern society,” since any ordained pastor engages in the “kind of authoritative teaching role which Paul forbids for women.”

So argued John Piper and Wayne Grudem, respectively, one decade before they helped to draft the Danvers Statement and then found the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood. About thirty pages into Beth’s book, they show up as editors of Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, the 1991 book that our co-blogger Kristin Du Mez (in her own must-discussed book) calls “a manifesto in defense of God-given gender difference.” Few evangelical theologians have done more than Piper and Grudem to advance the constructs of “biblical manhood and womanhood” that Beth and Kristin are helping to dismantle.

While they’re now better associated with other evangelical organizations and movements, I can’t help but think of Piper and Grudem as two of my predecessors on the Bethel faculty (which they left in 1980 and 1981, respectively) who have significant ties to its denomination, the Baptist General Conference. Even before coming to Bethel, Grudem had been ordained by the BGC congregation in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, and Piper went from the BGC’s college to a church that had long been a pillar of the same denomination. (Founded in 1871 — the same year as Bethel — First Swedish Baptist Church of Minneapolis changed its name to Bethlehem Baptist in 1945, the same year that the BGC also dropped Swedish from its title.) In opposing the ordination of women, they surely reflected the sentiments of the vast majority of Conference Baptists at the time.

In 1980, the denominational magazine, The Standard, editorialized that “God sovereignly bestows His gifts for the work of teaching and serving, regardless of sex, but it seems he has given the position of leadership in the church to men.” That summer, the BGC annual meeting declined even to discuss a resolution on “The Role of Women in the Church.” That year marked the publication of Fuller Seminary professor Paul Jewett’s book arguing for The Ordination of Women, which Piper reviewed for The Standard. Rejecting Jewett’s argument “that God is equally like man and women; hence, men and women are equally qualified to speak for Him as His ministers,” Piper concluded, “Whether or not God is more like man than woman, both the Living Word and Written Word reveal Him primarily in masculine images, because these are the images which humans need to be struck with above all in order to feel their own finitude and absolute dependence on Him.”

At the same time, a significant minority within the BGC had long agreed with Jewett. Even the 1980 Standard editorial reserving leadership to men started with a remarkable acknowledgment: “Pastoral service by ordained women in the Baptist General Conference has been a quiet, almost unobserved phenomenon for decades, and no noticeable protest has been registered, at least in recent years.” (One day I’ll tell the story of Ethel Ruff, ordained in St. Paul in 1943.) The editors also took seriously the principles of Baptist ecclesiology: it was for the local church to ordain pastors, not the denomination, and “the decision to ordain or not to ordain is the prerogative of the church.” In 1985 the BGC board adopted a statement emphasizing that “the majority of Conference Baptists believe that the scriptural data support the practice of an ordained male serving in the role of senior pastor (1 Tim. 3:1-7, Titus 1:5-9),” yet those same trustees declined to bar women from that very role. “Since Conference Baptists hold varying interpretations of the Scriptures as they apply to women in ministry,” they decided, “the issue of the ordination of women must not be permitted to become divisive to the fellowship (Eph. 4:2-3).”

By the end of the Eighties, some in the BGC wanted a more explicit endorsement of women in leadership. “In our effort not to become divisive,” wrote a woman from Anoka, Minnesota, “we forget that the Bible contains radical changes in the sinful social order… The church of Jesus Christ will never reach its full potential if we continue to ordain only men. Let’s recognize God’s call upon the lives of women, too!” Indeed, the BGC and its college and seminary had been home to some of evangelicalism’s strongest advocates for that very recognition.

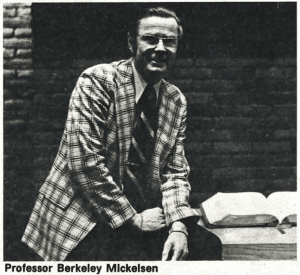

In the 1977 Clarion article, three other professors disagreed with Piper and Grudem, including the only one interviewed from the seminary faculty. A. Berkeley Mickelsen was as certain that women should be ordained as Wayne Grudem was that they should not. “Definitely yes,” he told the student reporter. Because they ignore the ways that the Bible “was written within a certain culture,” he continued, “people take regulations in the Bible and make them the highest ideal, norm or standard. This causes Paul to contradict Paul,” as culturally conditioned statements about some women in certain communities at a specific point in time obscured what Mickelsen took to be the apostle’s overriding theme: how the Gospel restores harmony where sin had caused conflict between groups, including women and men.

(Mickelsen’s seminary students at the time included Carol Shimmin, who became the first woman to earn a Bethel M.Div. in 1976. Ten years later, women accounted for just under 20% of the seminary’s student population. By the end of the twentieth century, that figure would near 30%.)

“They really felt the Bible was being misused to roll back a lot of women’s rights,” their daughter Lynnell said of Berkeley Mickelsen and his remarkable wife, Alvera (a Bethel journalism professor who contributed the egalitarian chapter to this 1989 InterVarsity Press book on evangelical views of women in minsitry). The Mickelsens went on to help found Christians for Biblical Equality, established one month after Piper and Grudem’s group. Through the years CBE’s supporters have included Bethel faculty like Virgil Olson, John Herzog, and our Patheos Evangelical colleague Roger Olson, whose endorsement of that organization holds out the “hope that its ministry will help to free both women and men from the bondage of cultural accommodation to hierarchical male domination in churches and families.” Several of my former students have gone on to work for CBE, including the author of this recent article on Paul as “an advocate in the fight for our equality.”

As I started reading Beth’s book over the weekend, all of this Bethel history came to mind, for complicated reasons:

First, it reminded me that — unlike Beth and many of her readers — I’ve spent most of my life in egalitarian corners of the evangelical world. Not only did I not grow up among evangelicals who trumpeted male headship and female submission, but I work at an evangelical institution where the preaching voice is often a woman’s voice: our campus pastor since 2008 has been Laurel Bunker, and recent chapel speakers have included Bethel Seminary graduates Heather Flies, Stephanie O’Brien, and Caitlyn Stenerson.

But if young men in the BGC (now doing business as “Converge”) aspiring to be pastors don’t want to have female peers or professors, they can attend the seminary spun off of Bethlehem Baptist. John Piper serves as chancellor of Bethlehem College and Seminary, its affirmation of faith explicitly reserves to men “the role of pastor-elder in the ministry of the Word and prayer,” and the only women listed on its faculty page teach English/literature or work in the library.

For that matter, only one of the Bethel chapel speakers I named above serves as the lead pastor of a Converge church. Our seminary continues to help women cultivate the gifts of preaching, teaching, and leadership, yet it’s still rare for its graduates to be called to such positions in its denomination. And even in Bethel’s College of Arts and Sciences, I’m sure that dozens of my female faculty colleagues could tell a version of Beth’s story about a theologically conservative, disruptively vocal male student who “expressed concern about my choice to continue teaching as a wife and mother….”

So as I read Beth’s book, I need to beware the danger of thinking that it describes a Christianity that’s distant from me. To a still significant extent, her story is the story of my colleagues and my students, of my employer and the churches that support it.

Indeed, the main emotion I felt as I read the first chapter of The Making of Biblical Womanhood was frustration. In those pages — as in the ministry of Christians for Biblical Equality, in Berkeley Mickelson’s 1977 interview, and in the earlier work of scholars like Katharine Bushnell — evangelical egalitarians argue again and again that patriarchy is a consequence of the Fall, not God’s divine design, and that the Scriptures both reflect a patriarchal culture and subvert it. Not only are they up against the ingrained attitudes of a religious culture that often affirms a militant version of masculinity, but I think Beth is right that egalitarians’ theological debate with complementarians “is in gridlock.”

So I hope she’s also right that “historical evidence about the origins of patriarchy can move the conversation forward.” While she’s certainly capable of engaging the argument on terms that would be familiar to Bible and theology professors like Piper, Grudem, and Mickelsen, Beth is a historian, adept at resurrecting ancient, medieval, and modern pasts where we can both see patriarchy being constructed and learn from earlier Christians whose faith led them to understand the role of women and men in non-complementarian terms.

I pray that Beth’s readers will indeed “listen not just to my experiences but also to the evidence I present as a historian” — an avowedly evangelical and Baptist historian “who believes in the birth, death, and resurrection of Jesus,” and so writes in the hope that the church itself can experience new life.

Postscript: I’m delighted that this post has found such a wide audience… but one consequence of that is that some readers are new to this blog and its conventions: one of which is that we almost always refer to each other by first name, to underscore how this blog is akin to an ongoing conversation, in which we frequently interact with the work of friends and colleagues. I don’t think I’ve ever referred to John as “Turner” or Philip as “Jenkins.”

At the same time, I completely understand why some readers have expressed concern that I refer to Beth Allison Barr and Kristin Kobes Du Mez (two of my Anxious Bench colleagues) as Beth and Kristin, while the various men referred to in the piece are called by last name: Piper, Grudem, Mickelsen, etc. In many academic and other professional contexts, that’s a real problem, subtly (or not so subtly) reinforcing a version of the inequality that Making of Biblical Womanhood tries to call out. It’s why, when I’m talking with students about my own department, I try consistently to call my fellow history professors Dr. Poppinga, Dr. Kooistra, and Dr. Goldberg, not Amy, AnneMarie, and Charlie.