Last week, a friend of mine recounted her experience working as a physician in New York City during the deadly first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic. This friend also happens to be a military veteran who deployed to Iraq in the early 2000s, and so I was intrigued to hear her description of serving as a frontline healthcare worker in March and April 2020. It was like a war, she said. For nearly two months straight, she witnessed unrelenting death, as patient after patient arrived at her hospital and succumbed to Covid-19.

She has not been the only one to draw parallels between pandemic and war. One of the most famous chronicler of the early days of the pandemic, Dr. Craig Smith of New York-Presbyterian Hospital and Columbia University Medical Center, wrote daily updates that read like messages from a battle-worn general. His updates, which were grisly in content and yet graceful in form, aimed not only to inform the world about the daily horrors he witnessed but also to steel the public’s courage—as he put it, to “balance terror with reassurance.” To do so, he drew regularly on military history and martial metaphors. For example, on March 25, only two weeks after the World Health Organization declared Covid-19 a global pandemic, Smith remarked that he was “mostly astonished by the explosion of energy and creativity being applied to the battle.” He quoted Emily Dickinson—“Not knowing when the dawn will come / I open every door”—and declared, “Doors are flinging open all over the place.” And by May 5, when the worst of the initial surge had passed, Smith wrote,

On this sunny Cinco de Mayo, why not celebrate victories? Whether we’re as outnumbered by the coronavirus as Zaragoza was by the French at Puebla depends on fanciful assumptions about relative biomass, but we have felt outnumbered…[But] wins balance losses. Victories bloom in cemetery soil.

The comparison between pandemic and war in many ways makes sense. The federal government used the Defense Production Act to create ventilators and vaccines. Communities prepared to build field hospitals to expand capacity during the most dangerous surges. And healthcare workers responded valiantly to fulfill their duty to care for their patients and serve their communities. Many thousands lost their lives in the process—and their deaths may have made the bloom of future victories possible.

Today is Memorial Day, a somber day when Americans mourn the loss of loved ones who died in military conflicts. But the immense death and suffering of the past year and a half, along with the observation of healthcare workers like Smith and my friend, force me to pause and reflect on what this holiday means to Americans in this particular moment, as Covid-19 cases fall in the U.S., as the number of vaccinated people rise, and as many more of us begin to resume life as normal. Thousands of healthcare workers lost their lives during the pandemic, and though there are certainly differences between a soldier in combat and a physician in a hospital, the shared themes of service and sacrifice make me wonder: how will remember those whose lives were lost fighting on the front lines in the war against Covid-19?

“a rededication to the martyred dead, to the spirit of sacrifice, and to the American vision”

To begin, it’s useful to consider the significance of Memorial Day as an aspect of American civil religion and as an articulation of the value of selfless sacrifice for the common good.

In 1967 the sociologist Robert Bellah made the famous observation that there “exists alongside of and rather clearly differentiated from the churches an elaborate and well-institutionalized civil religion in America.” The beliefs, symbols, and rituals that comprise this American civil religion are expressed in a variety of public ceremonies and collective acts of commemoration that articulate a distinctive “national religious self-understanding.”

In the United States, the observation of Memorial Day is an important ritual of American civil religion. Its origins lie in the Civil War, a moment when, as Bellah put it, “a new theme of death, sacrifice, and rebirth enter[ed] the new civil religion.” The 1860s saw the establishment of national cemeteries at Gettysburg and Arlington, which honored those who had died during wartime. Alongside these physical monuments were new public rituals—in particular, Memorial Day. As Bellah explained,

…the Memorial Day observance, especially in the towns and smaller cities of America, is a major event for the whole community involving a rededication to the martyred dead, to the spirit of sacrifice, and to the American vision. Just as Thanksgiving Day, which incidentally was securely institutionalized as an annual national holiday only under the presidency of Lincoln, serves to integrate the family into the civil religion, so Memorial Day has acted to integrate the local community into the national cult. Together with the less overtly religious Fourth of July and the more minor celebrations of Veterans Day and the birthdays of Washington and Lincoln, these two holidays provide an annual ritual calendar for the civil religion.

“akin to reading the names on a war memorial”

The “martyred dead” and the “spirit of sacrifice” that Memorial Day was designed to commemorate has focused traditionally on those who died in the specific context of war. But whom else might we memorialize if we embraced a different understanding of war and a broader definition of people who embody the “spirit of sacrifice”? We might consider, for example, healthcare workers who put themselves in harm’s way in order to care for their patients, even well before the Covid-19 pandemic.

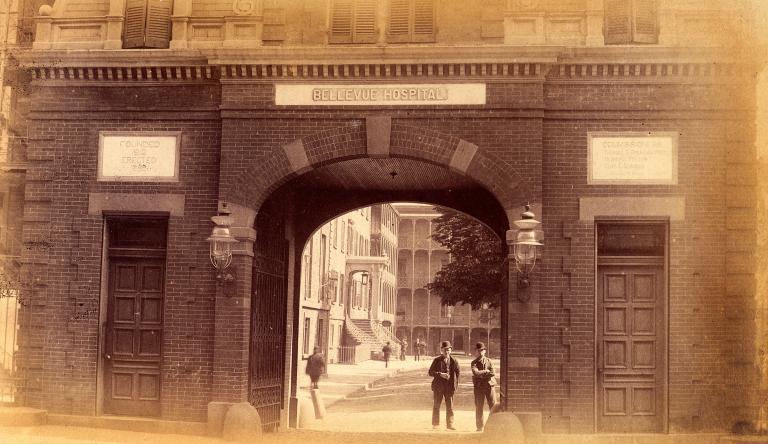

Take, for instance, the 1847-1848 typhus epidemic, known as “the Great Epidemic” at New York City’s Bellevue Hospital. (Bellevue, I should add, is where my husband trained as a surgeon for five years.) As David Oshinsky explained in his history of Bellevue, typhus primarily affected poor people, many of whom had recently disembarked the “famine ships” carrying Irish immigrants dislocated by the Potato Famine. Although many typhus victims died on ships or in homes, others sought treatment at Bellevue, where hundreds died and where the staggering caseload of typhus patients forced the hospital to pitch tents on its lawn. While Bellevue struggled to care for most of the city’s typhus patients, New York Hospital, which was located nearby, often dumped its sickest patients, which only added to Bellevue’s burden and exacerbated the hospital’s high mortality rate.

The patient death rate at Bellevue was a shocking 40%, and the death rate was even higher for the physicians and medical students who worked there. “To scroll through the fatalities in 1847-48 is akin to reading the names on a war memorial,” observed Oshinsky. In numerous entries, physicians’ and medical students’ cause of death was noted as “typhus fever, contracted while on duty at the hospital.” Throughout the ordeal, however, the staff at Bellevue remained committed to fulfilling their duty to care for the sick and dying—even when the physicians themselves were dying. “They remained at their posts through the worst of it, some rising from their deathbeds to train others to carry on,” Oshinsky wrote.

In the wake of the Great Epidemic, Bellevue came under scrutiny for the number of patients lost to typhus, and in response, the hospital restructured how it handled patient care. In the new system, Bellevue relied on a corps of recent medical school graduates known as “the house staff,” who were overseen by a team of “attending” physicians and surgeons and a smaller, more senior group of “consulting” physicians and surgeons. These positions were demanding and offered no remuneration. However, as Oshinsky pointed out, the roles of attending and consulting physician were “deeply coveted by the city’s medical elite as a sign of professional status and Christian duty.”

“Lost on the Frontline”

Healthcare workers have demonstrated a similar valor, sense of duty, and spirit of sacrifice during the Covid-19 pandemic. “Lost on the Frontline,” a joint effort by Kaiser Health News and The Guardian, has endeavored “to count and honor every US healthcare worker – whether doctors or custodians, nursing home aides or paramedics – who died after contracting the coronavirus on the job in the first year of the pandemic.”

The findings of “Lost on the Frontline” are sobering. As of April 2021, the project counted 3,607 healthcare workers who died of Covid-19 in the first year of the pandemic. More than half were under the age of 60. Nearly one-third of the deaths were nurses, with support staff also suffering high levels of death.

Some of the same patterns of inequality that have been observed elsewhere emerged in this project’s analysis. “Lost on the Frontline” found that the majority of healthcare workers who died were people of color. Many of the healthcare workers lost to Covid-19 had also expressed concern about inadequate personal protective equipment.

Finally, one-third of the healthcare workers who died were immigrants, and immigrants from the Philippines accounted for a disproportionate share of deaths. (As I discussed in a previous Anxious Bench post, this particular issue hits home for me. Filipino Americans have been hit hard by the pandemic. They account for 4% of American nurses but 31.5% of nurse deaths. Many of my Filipino American aunties, uncles, and cousins have been on the frontlines since the very beginning of the pandemic, serving some of the most impacted communities in New York, which is one of the two states that experienced the highest levels of healthcare worker death. One of my mother’s nursing school classmates died of Covid-19, along with her husband and son. All three were Filipino American nurses. Despite this fact, my mother, a paragon of courage and duty, still declared her own willingness to come out of retirement and return to the hospital to help.)

Healthcare workers have long endangered their lives in the name of caring for the sick. But while American civil religion readily honors “the spirit of sacrifice” of those who fought and died in wars, will we see a similar effort to honor the valor of healthcare workers? Over the past year, I’ve seen proud displays of pink hearts and banners to celebrate “healthcare heroes.” But once we return to normal life, will we take time to remember the pandemic? Will we remember the courage and resilience of the people who donned PPE and bravely walked into the hospital to face the terrifying unknown, while the rest of us stayed at home and baked banana bread? Will our understanding of duty, service, and sacrifice be capacious enough to include not only the soldier who dies in battle, but also the immigrant nurse who dies caring for the isolated elderly in an assisted living facility?

The sound of the hospital calling my husband is a distinctive one: a blaring horn, like the one that Boromir blows in The Lord of the Rings. This choice of ringtone is a practical one. When my husband is on call and the hospital needs him in the middle of the night, he requires a ringtone that can rouse him from his sleep. It almost always rouses me from my sleep, too, but when that happens, I’m never bothered. In fact, it’s an occasion for my favorite line. “It’s the Horn of Gondor,” I tell him, “and you’re being summoned to battle.”

As a surgeon and a military officer, he understands the importance of duty. He gets out of bed. He puts on his scrubs. He heads to the hospital to take care of his patients. He does all these things without complaint because these are responsibilities that he embraces wholeheartedly, perhaps at risk to himself.

So many healthcare workers who have worked on the frontlines of the pandemic have served their patients and their communities with courage, commitment, and compassion. Thousands have lost their lives in the process. As our nation moves toward claiming victory over Covid-19, will we remember those whose care and labor carried us through our darkest days? Will we remember their sacrifices?