At the end of my post last Tuesday, I alluded to a controversy brewing at Bethlehem Baptist Church in Minneapolis, Minnesota. So I’m grateful to Greg Rosauer for sharing a guest post today that expands on that story, and draws a helpful historical contrast with an earlier incident in the same city. Greg is associate professor and archivist at the Berntsen Library of the University of Northwestern-St. Paul, and a member of Trinity City Church in St. Paul, MN.

At the beginning of this summer, my pastor and I were reflecting on how Bethlehem Baptist Church (BBC) had a formative impact on us during our college years in the early 2000s. In particular, we recalled imbibing a disposition of seeing racial justice and justice for the unborn as commensurate and naturally allied goals. It wouldn’t dawn on us till years later how these themes of then-pastor John Piper were an odd couple for many American evangelicals. Thus, it surprised me when the successor of Piper’s Minneapolis pulpit, Jason Meyer, resigned due in part to charges that his attempt to address the city’s racial unrest subordinated the gospel to social justice ideology.

In his resignation letter, Meyer utilized a recent taxonomy of developing factions in evangelicalism to indicate that he no longer fits at Bethlehem. According to Meyer, BBC and its school, Bethlehem College & Seminary (BCS), are drifting towards neo-fundamentalism. Meyer is not name-calling here, but making an historical observation that others have seen as well. The polarizing force of national politics, compounded by COVID and racial unrest, has externalized the political and social impulses of American evangelicals. And (surprise!) evangelicals, even very conservative ones, display differing attitudes and dispositions toward culture. The label neo-fundamentalism refers back to the militant mentality of twentieth century fundamentalists who fought against perceived ideological and cultural threats to the gospel. Today, evangelicals and their institutions seem to be sorting themselves by their level of militancy against such threats.

That this has happened before in the mid-twentieth century is not news. But perhaps I can add an observation by comparing what is happening now at BBC and BCS with another church and school located in downtown Minneapolis more than 70 years ago.

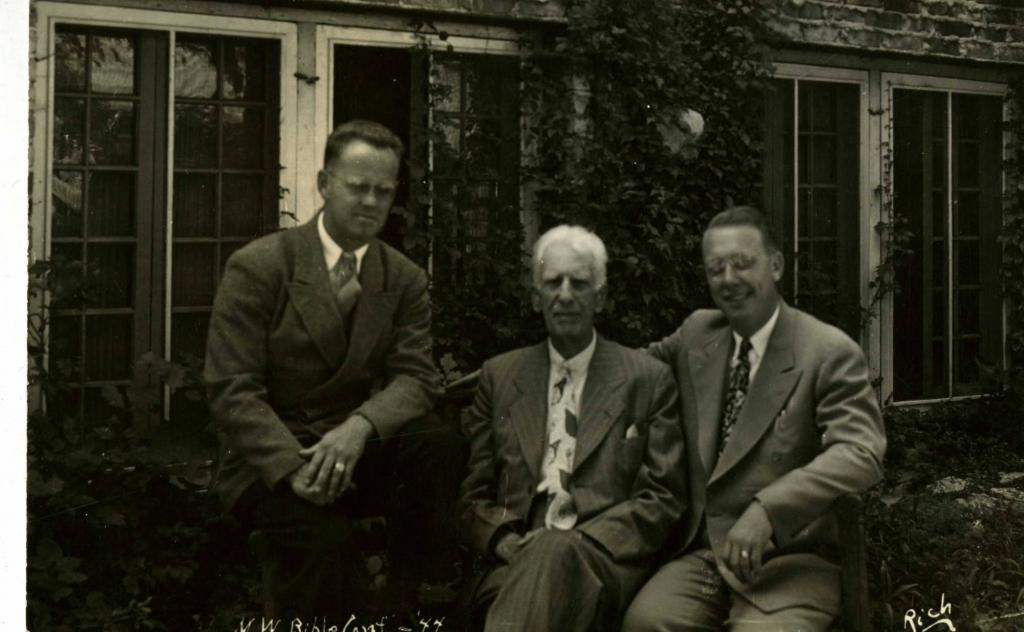

William Bell Riley (1861–1947) was a figurehead in the fundamentalist movement of the early twentieth century. He was the longtime pastor at First Baptist Church in Minneapolis and the founder and president of Northwestern Schools (a church-based Bible college and seminary). A prolific author and conference speaker, Riley expended most of his organizational and polemical skills attacking the “menace of modernism” (i.e., the encroachment of theological liberalism in denominations, schools, and culture). It is hard not to see the parallels with Piper, who also pastored a Baptist church in Minneapolis, is a prolific author and conference speaker, helped spark the neo-Calvinist movement, and founded a church-based college and seminary.

Both men were institution builders in their own way. However, the institutions they erected were/are dominated by their personalities. In Piper’s case, I think there is an awareness of the danger of personality-driven institutions, but try as he might there is no getting around the fact that the pews fill and the school recruits on the basis of John Piper’s “brand.” This is not necessarily a bad thing, but it is undoubtedly dangerous to be an evangelical celebrity (as a certain podcast has thoroughly reminded us of late). Riley knew very well the power of personality-driven movements, which impelled him to cajole a young man named Billy Graham to take the reins of his church-based school upon his death in 1947. Jason Meyer succeeded Piper as the pastor of the church in 2013, and not as the president of the school.

But despite this difference, Graham and Meyer inherited an institution from a founding leader who was virtually unassailable and essential to its identity. And by virtue of that status in the institution/movement, Riley and Piper had a critical level of trust amongst their constituents which the incoming leaders did not have. This trust allowed some constituents of the institution to downplay or deny aspects of Riley’s and Piper’s ministry with which they were uncomfortable. A different but glaring example of this dynamic happened a couple weekends ago when the former president, Donald Trump, spoke at a rally in Alabama and received boos from the crowd for suggesting that they should get vaccinated. The interesting thing about this is the way in which many otherwise loyal Trump supporters were never onboard with “operation warp speed” and are now openly hostile to what Trump sees as one of his major accomplishments.

The idiosyncrasies of Trump aside, I think a similar kind of disconnect happened when Riley stepped off the stage, and I suspect this is happening now with Piper’s slow exit. Things that Riley and Piper held together in their ministries were never comfortably joined in the minds of their constituents.

For Riley, the point of tension was his interdenominationalism. Though he was firmly Baptist, he designed his school to be interdenominational and promoted cooperative efforts in the fight against modernism. He also was not a separatist, though much of his rhetoric supported the growing impulse of fundamentalists to leave denominations tainted by liberalism. The tension between leaving or staying, fighting or cooperating animated the battles that ensued within mid-century fundamentalism. Graham was a fundamentalist, but he was not “a fighting ultra-fundamentalist.” By the 1940s, fundamentalism was splintering, and its most significant split, neo-evangelicalism, was happening right within Riley’s own school. As president, Graham was influenced by Carl F.H. Henry and Harold Ockenga to take Riley’s school in the neo-evangelical direction only to encounter significant resistance from separatistic “ultra-fundamentalists” at the school. The separatistic militant mentality of some collided with Graham’s cooperative evangelistic spirit, rendering Riley’s Northwestern Schools ungovernable even for a man of Graham’s talent. Many of Riley’s constituents had never accepted his interdenominational cooperative spirit. They liked the way he fought, but they always suspected that Riley’s cooperative efforts would result in compromise. Graham resigned the presidency in 1952 amidst charges that he compromised the gospel for worldly recognition and acceptance.[1]

Jason Meyer’s resignation in 2021 is eerily similar. As I mentioned, Piper was well known for emphasizing racial justice issues. In part this was a heritage of the neo-evangelicals in spaces like Wheaton and Fuller (where Piper was educated). But it seems that many under his ministry were always uncomfortable with addressing race and racism. Jason Meyer, like Graham before him, inherited an institution where ideological tensions could only be held together by an irreproachable and trusted founder. A contingent of BBC members, it seems, tolerated racial justice efforts under Piper but were always uncomfortable with them. As many pastors have found out, 2020 exacerbated the discomfort of discussing race. For BBC, that discomfort was manifested in open suspicion of Meyer’s commitment to the gospel, even by a few of Bethlehem’s own elders. Meyer, like Graham, was not afforded the same latitude of trust given to his predecessor. In other words: Meyer cannot be concerned about racial justice without suspicion of being “woke.” Just as Graham could not cooperate with non-fundamentalists without suspicion of being “liberal.”

The difference that had split the neo-evangelicals from the fundamentalists was not mainly doctrinal, but dispositional. In 1951 Graham attempted to temper the militant disposition of Riley by emphasizing Riley’s interdenominational spirit. The “fighting ultra-fundamentalists” reversed the emphasis. “A fundamentalist,” according to George Marsden’s casual definition, “is an evangelical who is angry about something.” Meyer, like Graham, was not sufficiently militant against liberalism or wokeism. Hence, Meyer’s sense that BBC and BCS are moving toward a neo-fundamentalism—i.e., a culture concerned to fight the encroachment of secular ideologies infiltrating the church and where care for the needs of the broken is a secularization subterfuge. In a church culture where compassion entails compromise, it is not enough to check off all the doctrinal boxes. Compassion can look too much like non-rational empathy. The fear—sometimes rightly founded—is that if we forfeit reason, we no longer have a Christian faith.

My hope is that Christians—of all stripes—will lay down the burden of suspicion towards one another and take up the humble confidence of our Lord, doing “everything without grumbling or arguing, so that we may become blameless and pure, ‘children of God without fault in a warped and crooked generation’” (Phi 2:14 NIV).

[1] This account is based on an article of mine: Greg Rosauer, “Billy Graham’s Northwestern Years (1948–1952): Emerging Evangelical and Fundamentalist Identities,” Fides et Historia 52, no. 1 (2020): 39–54.