Not surprisingly, a 2020 Games held in 2021 has made for an odd Olympics, with masked athletes entering empty venues in a country whose population isn’t sure it wanted the event to proceed. Yet there I was before church on Sunday morning, glued to my TV for live coverage of multiple track and field events. And it struck me that the Olympics, tainted as they always are, also illustrate sport’s most redemptive principle: that competition is actually cooperative, a kind of striving together.

At first blush, that sounds ridiculous. Doesn’t Olympic competition pit athletes and their countries against each other? Doesn’t the success of one require the failure of others?

In the Olympics’ signature event, the 100m dash, Lamont Marcell Jacobs of Italy claimed a surprising win in the men’s final. Jacobs wasn’t “on anyone’s top 10 list” coming into the games, said Peacock announcer Bill Spaulding. “That’s the magic of sport,” agreed his colleague, British runner Tim Hutchings. But it surely didn’t feel magical to U.S. champion Trayvon Bromell, who fell a millisecond short of qualifying for the finals and so removed one obstacle from Jacobs’ path to victory.

Of course, in a sport that makes much of the concept of “personal best,” it can also feel like runners, jumpers, and throwers primarily function as individuals, competing against themselves even more than their rivals. Entering the last round of the triple jump finals, Yulimar Rojas already had the gold clinched before she made her final attempt. Yet she gave her best effort of the event, leaping 15.67 meters to break a world record that had stood over for a quarter-century.

Remarkable as that individual achievement was, her victory also underscored that most national teams in the Olympics are not all that competitive. Rojas was the first Venezuelan to win a gold in athletics, and just the fourth winner in her country’s entire Olympic history. The Philippines had gone a century without gold until weightlifter Hidilyn Diaz lifted 224 kg last week, and almost a third of IOC members have never won so much as a bronze. Most of those countries are in the post-colonial world, making the Olympics just one more example of how geopolitical competitions for power and wealth continue to tilt supposedly-level playing fields.

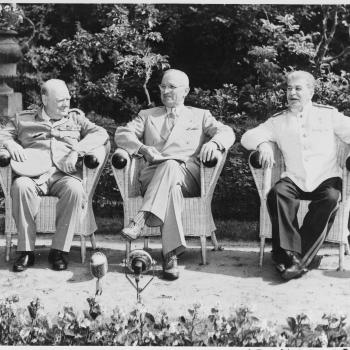

As the citizen of a country that won its thousandth gold medal in 2016, watching the Olympics even risks feeding a sense of national superiority. I was too young to remember the chants of “USA! USA!” from the Miracle on Ice, but four years later I felt like every one of my nation’s 83 gold medals in Los Angeles represented some kind of ideological triumph over the boycotting Soviets. The Cold War is long over, but every morning my son starts his day by checking to see if his nation is ahead of China and Russia; every morning, I worry that I’m helping to pass along a faith in American exceptionalism to another generation.

My pal Charles Lindbergh would tell me not to fret. (Have I mentioned that my biography of Lindbergh comes out two weeks from today?) “This world was not created on the basis of equality,” he wrote during World War II. “It was created, and it has always existed on the basis of superiority… God gave competition as a measure of the quality of life.”

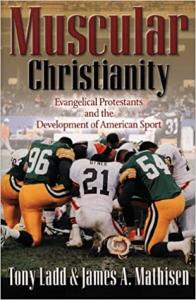

Incidentally, his belief in this kind of God is one reason he never embraced Christianity. “I think the essential value of competition is deplorably lacking in the marvelous philosophy of Jesus,” he complained in one letter; in another he decided that one weakness of Christian theology was its “blindness to the competitive qualities of life.”

Lindbergh clearly had never encountered the phenomenon of “muscular Christianity.” Just now, as I was drafting this post, I heard American swimmer Simone Manuel tell NBC studio host Rebecca Lowe that her success in Olympic competition brings glory to God.

Lindbergh clearly had never encountered the phenomenon of “muscular Christianity.” Just now, as I was drafting this post, I heard American swimmer Simone Manuel tell NBC studio host Rebecca Lowe that her success in Olympic competition brings glory to God.

But I’m not sure that Lindbergh (whose sporting career was limited to competing on a college rifle team) understood something that a Christian athlete like Manuel probably knows well: competition actually derives from a Latin word meaning “to strive together.”

That doesn’t mean that there are no winners and losers in Olympic events, but it does mean that competition is inherently cooperative. Some Christians have certainly emphasized this dimension of the Olympics. “When competition is viewed through the lens of striving together,” wrote sports researcher Landon Huffman and pastor Ed Goodman, during the Rio games,

whether in recreational soccer or Olympic track and field, competitors are regarded as comrades who embody and reflect God-given abilities rather than adversarial enemies who must be dominated and destroyed. Sport competition can therefore be enjoyed in the spirit of Proverbs 27:17, which states, “As iron sharpens iron, so a man sharpens the countenance of his friend.” Adopting a striving-together mentality of sport competition enhances relationships among all participants—teammates, opponents, coaches, and spectators—who can appreciate playful antagonism, diversity of skills within the body of Christ, and the beauty of God’s creation through human movement, relationships, and fellowship. Redemptive sport competition seeks God’s transcendent purpose for, and displays God’s glory through, participation in sport that emphasizes striving together.

As I wrote here that same summer, the Olympics can function as their own religion, a modern alternative to Christianity that worships nothing more transcendent than the ever-increasing accomplishments of humanity. But whatever the Tokyo Olympians’ personal religious beliefs and motivations, it wasn’t hard to see them exemplifying the “striving together mentality” on Sunday.

After Yulimar Rojas set her world record in the triple jump, she jumped into the embrace of Spanish athlete Ana Peleteiro, who seemed as thrilled for her rival as for her own bronze medal. Soon the TV feed cut to the stands, where coaches were hugging each other and athletes of all nationalities were filling in for absent fans to cheer on the competitors. While distant viewers like me are also (in a small sense) necessary to make Olympic competition possible, it’s those various individuals in the Tokyo National Stadium who knew best how they had each played necessary roles in the drama: without coaches to teach her, spectators to encourage her, fellow athletes to push her, and even officials to enforce her sport’s rules, Rojas could not have competed as she did.

Even more striking was the result of another field event: the high jump competition, which ended with the two leaders deciding to share the gold medal rather continue to a jump-off. Even a coach as relentlessly cheery as Ted Lasso claims to hate ties, but no one could despise the sight of Italian Gianmarco Tamberi leaping into the arms of Qatar’s Mutaz Essa Barshim. Having driven each other to new heights (literally), they shared the triumph — and emotions and memories that only a fellow competitor could grasp.

“Talk about Olympic spirit,” marveled analyst (and former Olympic runner) Alysia Montaño. “The Olympic spirit is to build a peaceful and better world,” she continued, “which requires mutual understanding with the spirit of friendship, solidarity, and fair play.” She echoed the Olympic oath, updated for Tokyo to more strongly affirm the value of equality while rejecting the any-means-necessary ethic that has often led individuals and nations to cheat their way to victory. Olympic athletes like Barshim, Tamberi, Rojas, and Peleteiro now pledge to compete in “the spirit of fair play, inclusion and equality. Together to stand in solidarity and commit ourselves to sport without doping, without cheating, without any form of discrimination.”

I’m not sure that’s a kind of competition that Charles Lindbergh would love, but it’s one that Christians should certainly celebrate.