A Christian liberal arts education is not supposed to be instrumental!

That’s what I wrote in my notes earlier this summer, listening to a seminar speaker discuss The Instrumental University, an insightful new book by Azusa Pacific history professor Ethan Schrum that begins with Clark Kerr, the architect of the post-WWII University of California system. While he found outmoded the notion of the university as an academic community united by a “central animating principle,” Kerr did think that the “series of communities and activities” that composed the modern “multiversity” strove after a common purpose. Higher education no longer glorified God or cultivated individual character for Kerr, nor was knowledge discovered for its own sake. Instead, the university was an instrument, valuable because it met the needs of government, industry, and other external constituencies.

That’s what I wrote in my notes earlier this summer, listening to a seminar speaker discuss The Instrumental University, an insightful new book by Azusa Pacific history professor Ethan Schrum that begins with Clark Kerr, the architect of the post-WWII University of California system. While he found outmoded the notion of the university as an academic community united by a “central animating principle,” Kerr did think that the “series of communities and activities” that composed the modern “multiversity” strove after a common purpose. Higher education no longer glorified God or cultivated individual character for Kerr, nor was knowledge discovered for its own sake. Instead, the university was an instrument, valuable because it met the needs of government, industry, and other external constituencies.

Schrum argues that Kerr’s view of education originally served progressive purposes — “[prioritizing] instrumental rationality to shape the social order” — and was intended primarily for research universities. But instrumentalism has long since spread throughout American higher education, as government and industry have found educational institutions of all sizes and types — including small Christian universities like mine and Schrum’s — useful instruments for other, not necessarily progressive purposes: preserving national security and training workers according to the needs of employers in a free market economy.

Which is how I find myself making arguments for the economic value of a history major that now ends with a seminar I’m teaching on “applied humanities”… within a Christian learning community whose “central animating principle” motivates us to work for the glory of God, the transformation of the whole person, and the pursuit of truth. We say that we seek after “permanent things”… but also promise to be more responsive to the fluctuating whims of impermanent economic and political systems. We claim to offer a liberating education… for the sake of preparing graduates to function within a neoliberal economy. We have a new president who insists that Bethel will remain the Christian liberal arts college he came to know as a Bethel undergraduate… majoring in business in preparation for a career in the corporate sector (save for a short stint as chief financial officer at Schrum’s university).

Such tensions seem inescapable. If I could wish away educational instrumentalism, I would. But I know enough of our 150-year history to know that Bethel has always been an instrument for external constituents. In fact, I suspect that the liberal arts came to Bethel — at the same time that Kerr built his multiversity — for instrumental reasons.

Here in late 2021, our students certainly seem to believe that Bethel exists primarily to meet the needs of employers in the private, public, and nonprofit sectors. Just look at the list of the most popular majors in this year’s entering class: business, nursing, education, social work, and STEM fields. (To be fair, most come in officially Undecided… but recent history suggests that most will decide on a professional program.) And while such an emphasis has grown more acute in recent years, as humanities and social science numbers have plummeted, it’s not actually new to Bethel.

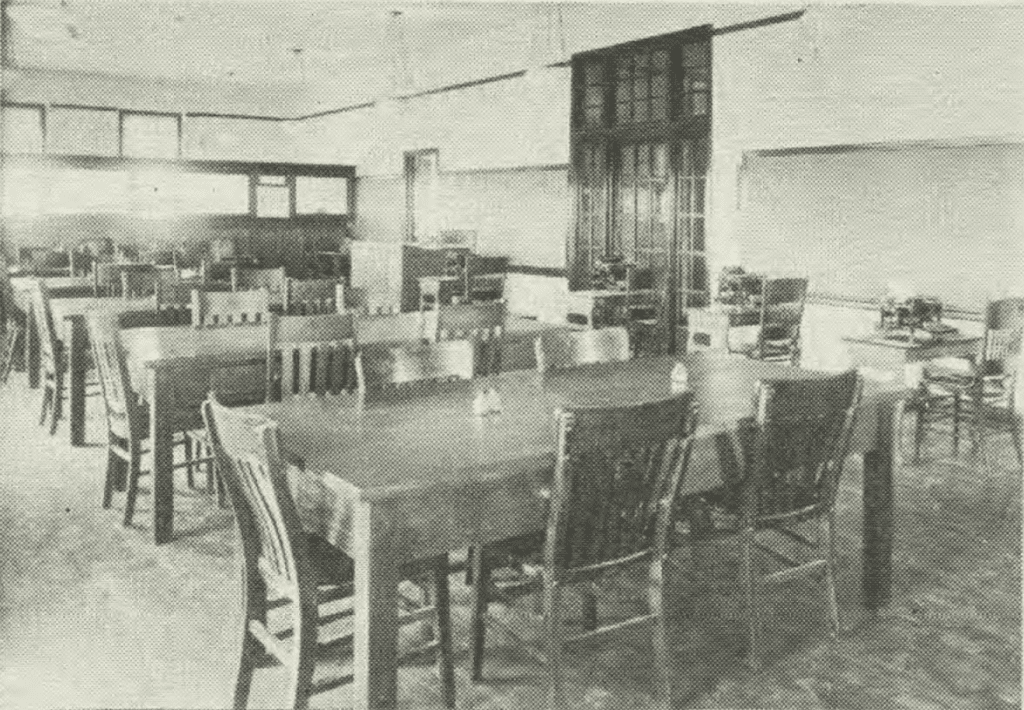

Our business and nursing programs — the two largest in the College of Arts and Sciences, with related programs in our adult and graduate schools — are each less than half a century old. But that kind of job training goes back to the birth of the university’s name. Bethel Academy was established at a Minneapolis church in 1905, providing dozens of first-generation Swedish Americans both biblical literacy and “rudimentary knowledge of English” — increasingly a prerequisite for employment in early 20th century Minnesota. By 1917 the Academy offered a distinct track for nursing preparation, plus a “commercial department” meant “to ground our students in those principles which alone make for permanent success in the commercial world,” through training in fields like bookkeeping, commercial law, “Business English,” and “Modern Office Methods.” That section of the Academy catalog began with a quotation from railroad tycoon and Bethel benefactor James J. Hill: “The demand for young people of brains and capacity in business is far and away beyond the supply. Capital is looking everywhere for the right person to direct it, and the men controlling capital will pay handsomely for such people.”

By then, most Academy students completed a general academic track that included subjects like languages, history, math, and sciences, to prepare them for further education: most likely either across the river, at the University of Minnesota, or across the Bethel campus in the Seminary building, where they would prepare for a career as a pastor or missionary.

That, after all, is the part of our university that gives us our founding date of 1871. From the outset, education at what we now call Bethel was meant to serve as a different kind of instrument for a different kind of external constituent: the Swedish Baptist churches that formally organized their General Conference in 1879. Twenty years later, the University of Chicago’s University Record proudly reported that all seven of that year’s Swedish seminary graduates — the last class of the 19th century — “have accepted calls to become pastors of different churches in this country,” making a total of 126 graduates to that point shepherding congregations in the U.S. — plus Canada, China, Finland, India, and Sweden.

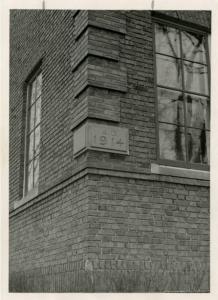

That seminary left Chicago and merged with Bethel Academy in 1914, the first year of World War I. But by the end of World War II, seminary education had evolved to the point that a master’s of divinity degree, and not the old B.D., was becoming the standard credential for professional clergy. So Bethel found itself losing students who had completed its two-year junior college program, gone elsewhere to finish their baccalaureate education, and never come back. To address that problem — and to meet another instrumental need: public schools’ heightened expectations for trained teachers — Bethel College converted to a four-year program in 1947.

It’s only at this point, I would argue, that Bethel started to become the “Christian liberal arts” institution that professors like me insist it has been, is now, and must ever remain. For explicitly instrumental ends, liberal education came to campus.

As far as I’ve been able to discover, the phrase “liberal arts” only entered Bethel’s official self-description after the junior college was founded in 1931. Even then, it was put in service of instrumentalism. The 1932-1933 catalog promised two years’ worth of study in English, foreign languages, natural sciences, social sciences (including history), physical education, and the Bible, but described that sequence as “the general Pre-professional Liberal Arts course,” with hopes expressed for “vocational and other courses” to come in the future. Fifteen years later, with the addition of a “limited though intensive senior college liberal arts curriculum,” the catalog emphasized that a “school is not an end in itself. Rather, it is organized to attain certain more or less well defined objectives for the constituency and for the students.” Alongside spiritual and personal growth, the liberal arts would fulfill “vocational objectives”: training for ministry, missions, and religious education, plus “the professional preparation of Christian young people who look forward to serving in the fields of secular education.”

From the start of the four-year program, majors included history, literature, philosophy, and psychology, alongside teacher training and pre-seminary options. But it wasn’t until the arrival of new president Carl H. Lundquist that Bethel leadership started to articulate a more robust understanding of why a liberal education was an important activity of a Christian college. For the fourth year of Lundquist’s tenure, the 1957-1958 catalog added a lengthy explanation of liberal arts that began with this paragraph:

The foremost aim of the program in the liberal arts at Bethel College is to help each person to realize his unique and sacred potentialities and to make his own best contribution to society. The liberal arts, consequently, are not defined primarily in terms of particular kinds of courses or subject matter but are distinctive in terms of basic spirit and purpose and include all aspects of campus experience. The college attempts to provide an intellectual, social, and spiritual community in which individuals can grow and learn in a variety of situations, are encouraged to assume responsibility intelligently, and may develop a discriminating awareness of and concern for Christian motives.

The catalog nodded to the continuing importance of “preministerial and lay leadership training” and the acquisition of “specific vocational knowledge and skills which enable students to enter into specialized fields.” But the primary emphasis was now on “general or liberal education, on the assumption that a college experience should bring a student to know himself, to appreciate his intellectual and cultural heritage, to understand the world and society in which he lives, to exercise critical judgment, to be intellectually alert, and to work effectively with other people.”

Explaining what was distinctive about education at Bethel in a 1961 report to the Baptist General Conference, Lundquist started with the importance of freedom, which he said “belongs to our Baptist heritage,” but also “to the liberal arts.

In the long evolution of the meaning of a liberal education it has progressed from being education for the “free” man in the early Greek and Roman world to being education that “frees” man in our world. It is in the nature of a liberal arts education to free men from ignorance, superstition, provincialism, and uncritical reasoning.

While Lundquist didn’t share the suspicion many fellow Conference Baptists felt for the idea of “Christian liberal arts,” he did see a threat to Bethel’s religious character coming from another direction: Clark Kerr’s model of higher education. In 1963, the year that Kerr published The Uses of the University, Lundquist warned Bethel’s denomination that “we do not have a uni-versity so much as a multi-versity” if God is not at its center. “Truth ultimately is God,” he wrote, “and God is truth.”

This timeless reality, and not the changeable needs of government or industry, gave “ultimate meaning to all truth—even to scientific truth in this age of space exploration.” So while Kerr developed his idea of the research university at a secular institution meant to be an instrument for the state and the market, Lundquist’s Christian liberal arts college held out the possibility that learning was an intrinsic good.

Sixty years later, Bethel advertises itself as forming “whole and holy persons,” Christ-followers who pursue truth and character… but who also have the skills and knowledge to fill needed roles in our economy and polity. We try to hold both goals — both instrumental and liberal models of education — in tension. But in the next post in this series, I’ll ask if our external constituents will continue to regard Christian liberal arts colleges as useful instruments.

<<Read the first post in this series | Read the next post in this series>>