Whatever else I accomplish in my academic career, I think I can assert one claim to fame: I think I’m the first American to have attended two American institutions of higher learning in the years they turned 300. I started my bachelor’s degree at the College of William and Mary in 1993, three hundred years after that royal couple chartered a school in Williamsburg, Virginia as “a certain Place of Universal Study, a perpetual College of Divinity, Philosophy, Languages, and other good arts and sciences…to be supported and maintained, in all time coming.”[1] Then eight years later I was wrapping up my doctorate at Yale University when it concluded its third century and started its fourth.[2]

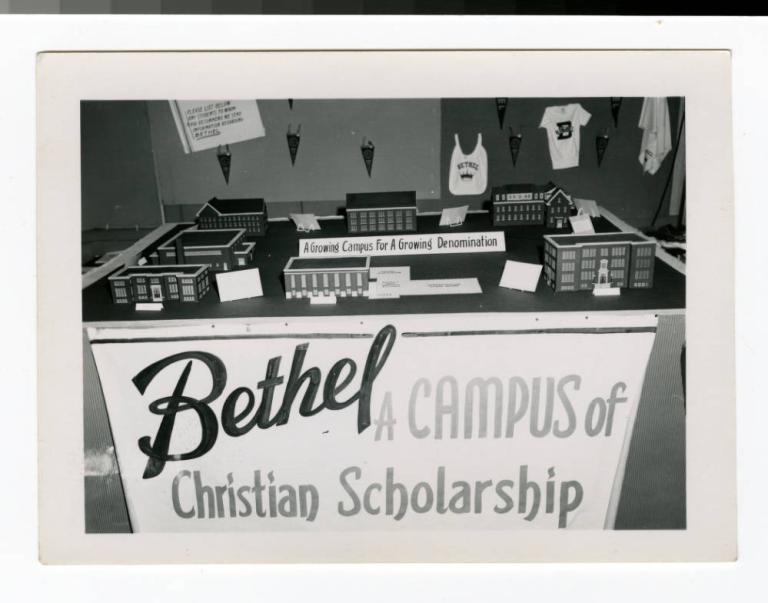

If that’s an accomplishment, it’s a trivial one. But perhaps it helps explain why I’m as eager as any of my employer’s alumni to observe Bethel University’s 150th anniversary this fall.

Maybe especially for institutions whose entire purpose is to propel people into their futures, it’s important to have milestones that remind us to remember the past that we’ve inherited. For if you work at an institution whose history spans multiple centuries, you’re always building on — or tearing down — what’s already built up. I’d rather we do so knowingly than not.

So this fall I want to mark Bethel’s sesquicentennial by writing occasional posts about its history — for the sake of the few readers here who are connected to Bethel, but also because themes in its story will sound familiar to the many more out there who have studied or worked at other Christian colleges.

To set up that series, let me start by telling a short version of Bethel’s 150-year story.

What I’ll do is repeat the trick I pulled three weeks ago, when I was asked to introduce Bethel’s history to its newest faculty members. Thirty minutes wasn’t a long time to cover fifteen decades, so I adapted Mark Noll’s strategy of emphasizing a few “turning points” and focused on five of our 150 years, trying to space them about thirty years apart.

1871

The beginning is always a good place to start, and Bethel’s beginning is more dramatic and ignominious than most: poor immigrants studying for ministry amid the embers of the Great Chicago Fire.

About twenty years after pietistic Swedish Baptist immigrants began to organize in the United States, a preacher, polymath, and Union Navy veteran named John Alexis Edgren organized a new seminary in Chicago. Its intended host — the First Swedish Baptist Church — had burned down, so Edgren opened his school as the Swedish department of the Baptist Theological Union. At first, there was but one student, with a second joining halfway through the year. Slow growth continued over a difficult first twenty years. After temporary moves to St. Paul, Minnesota and Stromsburg, Nebraska — plus Edgren’s bitter departure to California — the Swedish Baptist Theological Seminary returned to the Morgan Park neighborhood of Chicago and renewed a complicated relationship with the University of Chicago (revived in 1891 by a million-dollar gift from John D. Rockefeller).

1914

For reasons we don’t need to dive into right now, the Swedish Baptists’ seminary returned to St. Paul, Minnesota in 1914, merging with a nine-year old high school called Bethel Academy. Even as World War I broke out in Europe, Bethel Academy and Seminary erected buildings across the road from the Minnesota State Fairgrounds. (Key funding came from the Minnesotan rail baron James J. Hill.) Barely surviving a global conflict that shuttered a sister school in Seattle, Bethel grew in the 1920s, with the seminary gradually joining the academy in adopting English as its language of instruction. The academy didn’t survive the Great Depression, closing in 1936, but a new junior college (est. 1931) continued, even absorbing a small seminary program meant primarily to train women for foreign missions work.

1947

Then-Bethel Institute struggled to stay afloat during World War II, when most college students either entered the military or took good-paying war industry jobs. But the G.I. Bill spurred a postwar surge in enrollment, to the point that Bethel not only had an American Legion post on campus but had to house some of its students in a fairgrounds building unaffectionately called Hotel El Barno.

At once to accommodate the more expansive expectations of those federally-funded students and to meet new requirements for the training of pastors and teachers, Bethel College became a four-year institution in 1947. “Perhaps not even the bravest of our forebears included such a picture in his dreams of faith,” rejoiced the denomination’s magazine. “Doors are ajar to great vistas of service for Christ in the field of Christian education.”

1972

In 1954 Bethel hired a new president, Baptist pastor Carl H. Lundquist, who both linked Bethel to the larger neo-evangelical movement (serving as president of the National Association of Evangelicals in 1978-1980) and helped the school find a more distinctive religious heritage in Pietism. By the time he retired, in 1982, the student body had doubled in size twice.

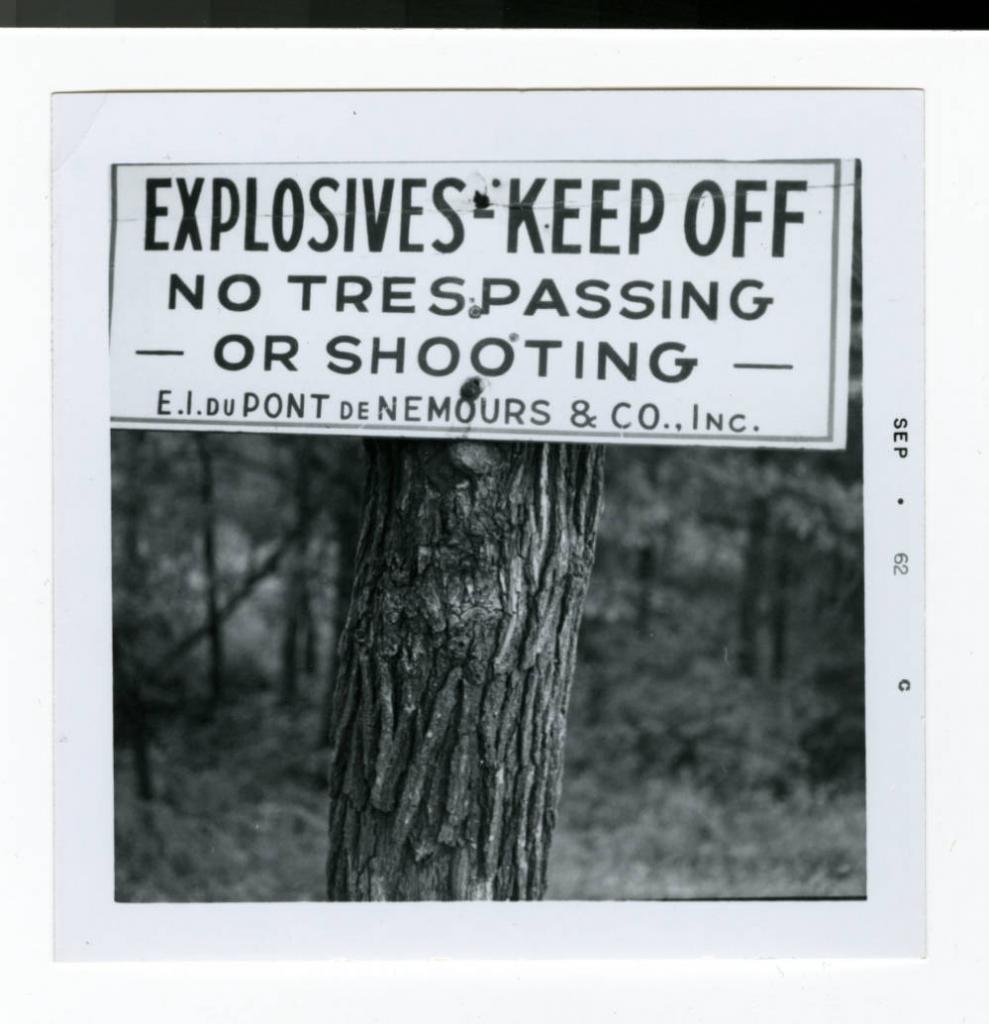

Under that kind of demographic pressure, Bethel soon outgrew its urban campus. After purchasing over 200 lakeside acres of former dynamite testing grounds from the DuPont Company, Bethel began to relocate to the tiny suburb of Arden Hills: the seminary in 1965, then the college seven years later. Also in the Seventies, the seminary added a West Coast campus in San Diego.

2004

Lundquist’s successor, academic dean George Brushaber, immediately faced an enrollment crisis in the mid-1980s. But Bethel resumed its pattern of growth as the twentieth century ended: not only in the college, but with the beginning of the school’s first degree completion and non-seminary graduate programs. Bethel College and Seminary became Bethel University in 2004. Having already presided over the construction of a still-stunning concert hall and a new senior dorm, Brushaber left office in 2008 as a new student commons bearing his name neared completion…

…and at the same time that the Great Recession caused the unemployment rate and home foreclosure rate in Minnesota to double. It’s too early to tell whether that economic event makes for a more important turning point than the shift to a university model, but suffice it to say that our college enrollment (both traditional and adult) peaked about ten years ago and has been in decline ever since. There have been multiple rounds of personnel reductions and program eliminations in that decade, and the San Diego campus of the Seminary closed.

As we mark a sesquicentennial amid yet another of Bethel’s periodic downturns, I have some grave concerns about the challenges facing our institution — most of them to be found at many other private religious colleges and universities. I’ll use some posts in this occasional series to reflect on some of those problems.

But it’s not the first time that Bethel has gone through ups and downs. So while G.W. Carlson and Diana Magnuson wrote Persevere, Läsare, and Clarion, their 125th anniversary history booklet, as Bethel was reviving its late 20th century fortunes, I echo the hopefulness of their concluding paragraph, which is rooted in something deeper than the economics of higher ed:

One can be hopeful about the future of a school with such a rich spiritual and cultural heritage. Recording, understanding, and celebrating that heritage is necessary if we are to have an appropriate perspective for current and future discussions about the educational mission and what Bethel will be in the future. That future holds great promise based on Bethel’s past ability to “persevere” throughout economic crises and theological challenges. One can be hopeful because Bethel values its “läsare” heritage where the Bible is revered as God’s Word for the modern age.[3] One can be hopeful about the future because Bethel maintains its commitment to being a “clarion” community committed to continually proclaiming the Word of God at home and abroad.[4]

Read the next post in this series>>

[1] While my undergraduate alma mater never fails to trumpet its relative (for the U.S.) antiquity, let this W&M alum acknowledge that “all time coming” isn’t quite the full story. William and Mary shut down during the Civil War, didn’t reopen until 1869, then closed for lack of funds between 1881 and 1889.

[2] I suppose someone could have studied at Harvard during its 1936 tercentenary and then come back to W&M or Yale over half a century later, but that seems unlikely.

[3] Swedish for “readers,” the läsare carried the Pietist revival of the 1840s to the countryside, defying the state church to organize small group Bible studies.

[4] The Bethel student newspaper has been called The Clarion since the 1920s.