I didn’t mean to write this post.

I’m still undecided what purpose a response to Kevin DeYoung’s review of The Making of Biblical Womanhood would serve. For starters, I’ll never be as funny as Michael Bird. I don’t think a response by me will impact DeYoung. I don’t think he really cares to engage me (see my assessment of his review as compared to that of medieval historian Katherine French). I suspect that the goal of the review was to discredit me so that people wouldn’t read my book. Afterall, The Making of Biblical Womanhood is dangerous to complementarianism (the vehemence of DeYoung’s 5,000 word review proves this). I’m also pretty doubtful that folk who gleefully retweeted his review will listen to a response from me. Did you know that the same day DeYoung published his review trying to undermine my scholarly credentials, a well-respected historian in my field published her own endorsement of The Making of Biblical Womanhood? Sara M. Butler, the King George III Professor of British History at Ohio State University who–just like me–specializes in late medieval England, named it as one of the best books on women in the Middle Ages.

Listen to what she said: “The [SBC] argues that [complementarianism] is grounded in the Bible–but as a historian of medieval Christianity, Barr knows this is not the case. Using her training as a historian, Barr debunks this mythology, highlighting how women shaped early Christianity through their roles as mystics and theologians up until the Protestant Reformation.”

So if the TGC and CBMW crowd are going to accept the ad hominem attack of Kevin DeYoung over the assessment of a top scholar in my field, why would they listen to even more words written by me?

I did decide to address his review in one area: the treatment of medieval women. While DeYoung’s response to Brigit of Kildare, Genovefa of Paris, and Margery Kempe mostly made me roll my eyes (and, like my daughter, I’m a really good eye roller), I know that I have an advantage. You see, I really am a medieval women’s historian, making DeYoung’s concerns easy for me to brush off. But this isn’t as easy for folk unfamiliar with medieval history. So I wrote a response that I meant to post today.

Until I changed my mind. I was responding to a reader’s question about the ESV (the English Standard Version Bible) and realized it also addressed one of DeYoung’s criticisms. Instead of sending this response only to the reader, I decided to share it with you. I’ll save my medieval response for November.

This is what The Making Biblical Womanhood reader asked me: what evidence did I have that

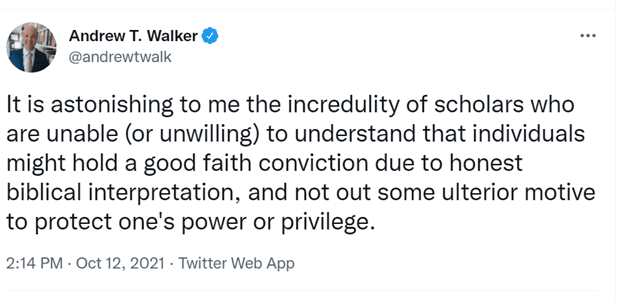

the ESV committee was intentionally pushing a complementarian agenda? This struck me as similar to what Kevin DeYoung asked in his review: how could I have “confidentally ascertained the inner workings of the ESV translation committee”? For those of you paying attention, both of these questions smack of a very recent statement made on Twitter by Andrew Walker, a professor at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary (the SBC flagship seminary in Louisville, KY) and an editor at World magazine. “It is astonishing to me,” Walker wrote, “the incredulity of scholars who are unable (or unwilling) to understand that individuals might hold a good faith conviction due to honest biblical interpretation, and not out [of] some ulterior motive to protect one’s power or privilege.”

The context of each question differs, yet each conveys a similar message: is it possible that complementarianism (or the white conservative Christian worldview in Walker’s case) simply reflects “honest biblical interpretation”? This is a great question. It is a question that I have asked myself. So let me walk you through how I tackled it–specifically, how can I “confidently” assert that a complementarian agenda shaped the ESV.

First, there is the evidence of the ESV itself. In 2019/2020, sociologist Samuel Perry (co author with Andrew Whitehead of Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States) published a fascinating article in the Sociology of Religion Journal (Volume 81:1, pp. 68-92). Titled The Bible as a Product of Cultural Power: The Case of Gender Ideology in the English Standard Version, Perry analyzed 16 biblical passages often used in the complementarian/egalitarian debates, comparing the ESV with the RSV. He found that while 7 of the passages were mostly unchanged, the remaining 9 were altered in the ESV to support a complementarian reading. As Perry writes, “nine of these gender passages were changed and each was altered in the direction of favoring a more complementarian, traditional gender interpretation.” For example, the RSV describes Phoebe in Romans 16:1 as a deaconess of the church at Cenchrea; the ESV describes her as a servant. 1 Timothy 5 in the RSV translates verse 14 as, “so I would have younger widows marry, bear children, rule their households”; the ESV alters “rule their households” to “manage their household.” Perry suggests that the ESV softens “rule” to “manage.” Why? Perhaps because in the complementarian framework only men can rule the household which means women can only be managing it. As Perry writes, “The ESV changes only this word to “manage their households,” thereby softening the meaning to suggest that young wives are merely managers of the home, in which men are expected to rule.” Perry lays out his textual comparison in a series of stunning tables, arguing that “those who read the RSV or the ESV would receive fundamentally different messages in key texts that many theologically conservative Protestants cite as foundational to their doctrines.” Because of how the ESV translates texts about women, conservative evangelicals might believe that women neither did nor could hold leadership positions in the early church. Junia is only well known to the apostles (rather than an apostle herself), Phoebe is only a servant (rather than a deacon or deaconess), and the curse laid on women in the garden is to rebel against their subordinate position (“your desire shall be contrary to your husband, but he shall rule over you). I still regret not finding this article before I published The Making of Biblical Womanhood. I would have cited it ad nauseam within chapter 5…..

The textual evidence is pretty straightforward: the ESV translates key passages to more firmly support a complementarian reading. But, again, is this because of the motives of the ESV committee? Let’s move to my second line of reasoning.

In 2008 I redesigned an old course for the Baylor History department. It was my first year on tenure-track, and the course was historiography. The title is not sexy, but the content literally forms the foundation of the historical discipline. It is the study of how and why historians do what we do (our methodology). The first assignment I designed for the course was a “perspectives essay”. I asked students to engage in a short research project about the life and training of a known historian. Students would frame their essays around this question: what is it about the personal character, life experiences, and/or academic training of the historian which influenced the way they saw history? The second assignment I designed was a source analysis. Students would learn how to interpret sources reliably by investigating the historical context of a source as well as the perspective of its creators.

Let’s see what we find when we apply these basic methodological tools to the ESV.

- We find an all-star male cast. Marg Mowczko calls the ESV Bible a “Men-only Club”. “It is not only the [95] contributors to the ESV Study Bible that are all male,” she writes.” The members of the ESV Oversight Committee, as well as the Review Scholars, are all, and only, male.” Go look for yourself.

- We find the majority of contributors are complementarian. As Mowczko also observes, “The list of contributors to the ESV Study Bible is easy to find online. When I looked at the list for myself, I found, with a few exceptions, a veritable who’s who of many of the most well-known hierarchical complementarians.” Again, go look for yourself. 10 of the 13 current members of the ESV Oversight Committee are clearly complementarian (I looked them up to verify), and I suspect 2 of the remaining 3 are as well (although I couldn’t find iron-clad evidence). You will find prominent complementarians (including SBC and Council for Biblical Manhood and Womanhood names) scattered throughout all levels of the ESV Oversight Committee, Review Scholars, and Advisory Council. Several of these folk (like the Pattersons) were involved in the 2000 Baptist Faith & Message as well as the earlier Danvers Statement.

- We find a least one significant participant in the ESV Study Bible accused prominent complementarian Wayne Grudem’s “dogmatic theology” as ruling “the exegesis of the text.” Synoptic Gospel scholar Robert Stein refused to let his name stand with his contributions to the ESV Study Bible in Luke because Grudem changed his notes. As Stein said, “This cannot stand…this is simply not true. You’ve changed the meaning, and it is no longer true to the text.” (Just think about the implications of this…..)

- We find the ESV is published by a complementarian press. The ESV is published by Crossway which, at least at the time, did not publish egalitarian works. “GNP/Crossway will not publish a work that is egalitarian. Marvin Padgett, vice president, editorial of GNP Crossway says Crossway sees the complementarian view of gender roles in both the home and church as the clear teaching of Scripture.” (Does anyone know if this is still the case???)

- We find that the Council for Biblical Manhood and Womanhood applauded the publication of the ESV Literary Study Bible as taking “an unapologetically biblical stance on God’s gracious plan regarding the complementary roles of men and women.” The CBMW, in other words, called a publication of the ESV unapologetically complementarian. (I hope you are noticing a pattern….)

- We find evidence that the ESV was born in the Gender-Neutral Bible controversy and connected, from the very beginning, with the Council for Biblical Manhood and Womanhood. (BTW check out my conversation with Scot McKnight where he tells his up-close-and-personal account with the ESV).

So where does this leave us? I was not an eye-witness to the translation decisions made for the ESV. But the evidence that the ESV was created by complementarians with a complementarian agenda to further complementarianism is pretty overwhelming. I’ll just leave you with this final thought: if it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it is probably a duck…

And, as a historian, that is about all I have to say (at least until November).