This blog concerns a complaint I often have when I read Christian history, which in an English-language context is all too often written as if Christian is synonymous with Protestant, and that alone. As I will suggest, not only is far more happening in the Catholic context than is known to most non-specialists, but that Catholic story has uncanny parallels to the familiar Protestant tale. Comparing the two stories offers powerful lessons for understanding landmark events in Christian history, including the Great Awakenings and the rise of evangelicalism.

In 1749, Henry Fielding’s novel Tom Jones featured the slimy parson Thwackum, who notoriously declared that “When I mention religion, I mean the Christian religion; and not only the Christian religion, but the Protestant religion; and not only the Protestant religion, but the Church of England.” Scholars have moved far beyond that bigoted stance, but an unconscious Protestant predilection is still sometimes in evidence. Traditionally, books on Christian history might include a well-intentioned and even sympathetic chapter on the Roman Catholic tradition as it existed from, say, the sixteenth century through the twentieth, but this is always subsidiary to the main thrust of the story. Catholics are voices off stage. I have read so many histories of Christian missions to region X that all but omit the long story of Catholic efforts in the Early Modern period, and assume that the real story began with the Protestant arrivals after 1800. Such neglect of the Catholic angle need not arise from any conscious prejudice. Often, Protestant historians tend to think that Catholic matters were much less eventful, because the Catholic faithful were generally passive, disciplined, docile, and uncritical of authority or hierarchy. Hence, Catholics produced nothing like the same factionalism, the same tendency to spawn sects and movements. (Catholic readers: feel free to chuckle here).

Here, let me offer one case-study. It is not necessarily the most significant, but it does highlight the major themes.

The Protestant Awakening

If you have read any history of Christianity in the eighteenth century, you know something about the familiar roster of names – the Wesleys, Whitefield, Jonathan Edwards, and the leaders of the Great Revival. You also know the standard range of locations, in the British Isles and the American colonies, including the Caribbean, in Protestant Germany and Central Europe. The resulting story is one of intense concern about piety, of fiercely revivalist religion and commitment to personal faith and conversion. You also know that the various movements often spilled over into wild excesses, of extravagant emotionalism, with claims of miracles, healings, and signs of the End Times – of what the Earl of Shaftesbury would have called Religious Panics. Mainstream revival leaders fought hard to contain such extremism, or in the language of the day, “enthusiasm,” that is, being filled with God, thous. Repeatedly, those leaders faced the challenge of how far these new currents could be constrained within older ecclesiastical structures, and conservative or reactionary clergy were freely denounced.

So (we are led to believe), if you want to understand eighteenth century revivalism, you have to situate it in the history of Protestantism – of the German Lutheranism that begat Pietism, of the conflicts and schisms in American Puritanism, and the competing currents within the established churches of the British Isles. Revivalism was thus a Protestant response to a series of Protestant problems, movements, and crises.

Meanwhile, in the contemporary Catholic world … what? Look at a hundred books on revivalism in the Anglophone world, and try and find interfaith parallels. Very few are noted, or even glanced at. Of course there are some exceptions to that statement, but I think it is generally fair. Mark Noll, as always, stubbornly continues to confound my generalizations.

What About France?

So let me be specific: what about France? In the eighteenth century West, there were two key Great Powers, namely England and France. Each was a mighty military and imperial state, each operated on a global scale, each possessed very advanced science and technology, and the two vied for dominance of the intellectual world, and the related “soft power” that went with that hegemony. England, of course, was resolutely Protestant, and France was Catholic. And so, some might believe, the Anglophone world permitted wide-ranging religious experimentation and innovation, while Catholic France plodded along in faithful obedience to the Papacy.

The reality was absolutely different. During much of the eighteenth century, Christian France was deeply divided between religious currents, all notionally Catholic, but differing fundamentally on critical issues. For some, this was an era of – now what was that phrase again? – of piety, of fiercely revivalist religion and commitment to personal faith and conversion. And just as in the Anglosphere, some movements spilled over into sensational excesses, of extravagant emotionalism, with claims of miracles, healings, and signs of the End Times. Repeatedly, revival leaders faced the challenge of how far these new currents could be constrained within older ecclesiastical structures, and conservative or reactionary clergy were freely denounced. If John Wesley or Jonathan Edwards had visited France at various points in the 1730s, say, they would have had a powerful sense of recognition.

What’s the French for déjà vu?

I offer an essential primer about the movements I am describing. Between (say) the 1640s and 1789, the French church faced multiple conflicts. One concerned the degree of autonomy that the church should have, and its relationship to Rome. Some favored strongly nationalist solutions, in which the French monarchy would make the decisions. That monarchy was by far the most powerful in the Catholic world, and Popes had to tread very lightly handling those “Most Christian Kings.” Such national-oriented approach was Gallican, reminiscent of English Anglicanism. Others supported doing things exactly as happened in Papal-dominated Italy, “over the mountains,” (the Alps), and that view was thus ultramontane. Those divisions underlay so many other religious disputes through that era.

Theological divisions were bitter. From the 1630s onward, many pious believers had been attracted to Jansenism, which stressed the severity of Original Sin and human depravity, and taught predestination. This obviously bears many resemblances to Calvinism, while the central emphasis on faith and divine Grace resonates with the Lutheran world view. As with Luther and Calvin, the movement’s founders were profoundly influenced by Augustine. Indeed, its founding text was the Augustinus of Dutch Catholic bishop Cornelius Jansen, published posthumously in 1640. In the later seventeenth century, there were a great many parallels between Catholic Jansenists and Protestant Pietists. Still, those Jansenists unquestionably belonged to a Catholic setting, and the movement’s intellectual center was at a monastic house, at the abbey of Port-Royal-des-Champs.

Jansenist believers and communities were strict and rigorist, and they attracted such profound thinkers and advocates as Blaise Pascal. Many famous quotations serve to illustrate the movement’s rigor and severity, but typical are the words of theologian Pasquier Quesnel, “People want to be Christians too cheaply, and consequently they are not Christians at all. Salvation has to cost, it has to cost everything, at least as far as the disposition of the heart is concerned.” The Jansenists’ deadly enemies were the Jesuit order, which represented the voice of Rome, and ultramontane ideas.

Jansenists often found themselves in opposition to the established hierarchy. In 1713, tensions reached a climax when the Papal Apostolic Constitution of Unigenitus Dei Filius decisively condemned Jansenism. But the Jansenists did not go away, and sectarian warfare raged within the French church over the next two decades. Janesnists and their supporters struggled to oppose the Papal decision through a General Council. Heavily factionalized, Jansenists maintained their existence and their structures, particularly in certain highly visible communities.

Convulsionnaires

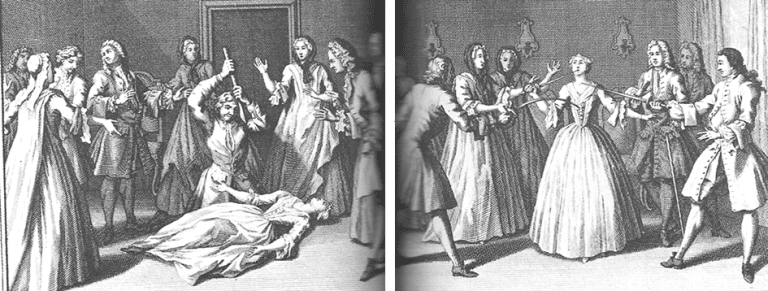

One stubborn Jansenist believer was the deacon François de Pâris (1690-1727) whose burial place at the Paris cemetery of Saint-Médard became the center of a martyr cult, complete with miracles and healings. Jansensists used the alleged signs and wonders to call for his canonization. Devotees followed millenarian ideas and deployed apocalyptic rhetoric, as they followed prophetic leaders. Pilgrims went into wild ecstasies and convulsions, which earned the movement the name of the Convulsionnaires. In the words of an orthodox Catholic history,

They pretended that at his tomb in the little cemetery of Saint-Médard, marvellous cures took place. A case alleged as such was examined by de Vintimille, Archbishop of Paris, who with proofs in hand declared it false and supposititious (1731). But other cures were claimed by the party, and so noised abroad that soon the sick and the curious flocked to the cemetery. The sick experienced strange agitations, nervous commotions, either real or simulated. They fell into violent transports and inveighed against the pope and the bishops, as the [Protestant] convulsionaries of Cévennes had denounced the papacy and the Mass. In the excited crowd women were especially noticeable, screaming, yelling, throwing themselves about, sometimes assuming the most astounding and unseemly postures. To justify these extravagances, complacent admirers had recourse to the theory of “figurism”. As in their eyes the fact of the general acceptance of the Bull “Unigenitus” was the apostasy predicted by the Apocalypse, so the ridiculous and revolting scenes enacted by their friends symbolized the state of upheaval which, according to them, involved everything in the Church.

The reference to the “convulsionaries of Cévennes” concerns the radical Camisards, whom I discussed in my recent column on the “French Prophets.”

Going back to the Catholic groups of the 1730s, as the Catholic Encyclopedia observes,

The convulsions reappeared in private houses with the same characteristics, but more glaring. Henceforth with few exceptions they seized only upon young girls, who, it was said, possessed a divine gift of healing. But what was more astonishing was that their bodies, subjected during the crisis to all sorts of painful tests, seemed at once insensible and invulnerable; they were not wounded by the sharpest instruments, or bruised by enormous weights or blows of incredible violence. A convulsionary, nicknamed “la Salamandre”, remained suspended for more than nine minutes above a fiery brazier, enveloped only in a sheet, which also remained intact in the midst of the flames. Tests of this sort had received in the language of the sect the denomination of secours, and the secouristes, or partisans of the secours, distinguished between the petits-secours and the grands-secours, only the latter being supposed to require supernatural force.

The cult-like movement – this classic eruption of ecstatic religion – is studied in Brian Strayer’s Suffering Saints: Jansensists and Convulsionnaires in France, 1640–1799 (Sussex Academic, 2008). As Strayer remarks,

The format of their séances changed perceptibly after 1732. Instead of emphasizing prayer, singing, and healing miracles, believers now participated in ‘spiritual marriages’ (which occasionally bore earthly children), encouraged violent convulsions …. and indulged in the secours (erotic and violent forms of torture), all of which reveals how neurotic the movement was becoming.

Forms of penance escalated to become what a modern observer would immediately recognize as powerfully sexual and sado-masochistic.

This was all bad enough, but in the mid-1730s, the movement was accused of becoming politically revolutionary, and seeking to overthrow the royal regime. The police ruthlessly stamped out the Convulsionnaires. Or at least they did their best to do so. Jansenist/Convulsionnaire sects continue to surface through the end of the century, and indeed after the French Revolution. (See Serge Maury’s recent book Une secte janséniste convulsionnaire sous la Révolution française: Les Fareinistes (1783-1805).

As in the Protestant revivals, the extremists were a small minority of the larger Jansenist movement, although their activities did serve to discredit the mainstream. That larger body of Jansenists survived and remained active, and campaigned against Papal power, against the ultramontanes, and above all, against the Jesuits. Some of those polemics relied heavily on scandal and charges of sexual depravity: see Mita Choudhury’s intriguingly titled book The Wanton Jesuit And The Wayward Saint: A Tale Of Sex, Religion, And Politics In Eighteenth-Century France (Penn State Press, 2015). Such frequent denunciations of the Jesuit order contributed much to the dissolution of that organization in the 1760s. Although this is way beyond the scope of this blogpost, that story becomes truly bizarre in the second half of the century, when the surviving Jansenists increasingly shared arguments and ideas with leading Enlightenment figures, who were of course very anti-religious.

Two Worlds

If we change the names, so much of this French experience would be instantly comprehensible in contemporary England, or to the American colonies. A loopy New England revivalist like James Davenport would have felt completely at home at the shrine of Saint-Médard. So would many observers of the frontier revivals of the 1790s during the Second Great Awakening. Putting aside the really excessive physical responses, the convulsions, the whole French affair points to a desperate spiritual hunger very much like that we see in England or America during the same years. Yet the responses were quite different. Jansenism did not evolve into a separate church equivalent to the Dissenters in England, or the Baptists or Presbyterians in the colonies. Even during the extreme social and cultural pressure of the climate shock in 1740-41, France produced nothing vaguely akin to the Great Awakening. There was no proliferation of sects, which would in their turn have become influential churches.

The obvious reason for this was the power of the nation’s Catholic church, and its reluctance to accept any rivals. But of itself, that is not a sufficient explanation. At least in theory, the Church of England likewise accepted no breakaways, and Dissenters were subject to severe civil and legal penalties into the nineteenth century.

To return to the period 1740-41, which marked the height of the Great Awakening movement in America, the issue of government control and police power does much to explain the religious manifestations of this particular crisis, and its geography. By far the best-known spiritual explosion of these years occurred in the English-speaking world, where internal political controls were weak by European standards and a high degree of religious freedom and self-expression was accepted, at least de facto. That was assuredly not the case in European states such as France or Prussia, where states not only distrusted and feared religious excesses but had elaborate mechanisms for enforcing internal security. Unlike in the British world, French believers who might have wished to pursue a spiritual revival or a new Awakening around 1740 (say) would very rapidly have fallen afoul of a tough-minded police force, complete with informers, secret agents, and draconian powers of imprisonment. This sensitivity was all the greater following the well-publicized lunacies of the Convulsionnaires in the mid-1730s. And although Pietists originated in the German-speaking lands, they enjoyed some of their greatest successes in the religiously tolerant British-ruled Transatlantic world. Revivals could and would occur only where opportunity permitted.

Why Awakenings Do Not Happen

A comparative study of those eighteenth century movements has many lessons, but the greatest one is perhaps this. In order to have a mass revival or religious awakening, it is not sufficient to have great preachers, or popular spiritual hunger, or new theological insights. There must be a state mechanism that allows groups actually to do such daring and innovative things. Moreover, that is not just a question of what an established church wishes to allow or prohibit, but how far the state cooperates with that establishment, and uses its police powers in its support. Unless we understand those state mechanisms – their presence or absence in particular societies – we cannot comprehend those celebrated Great Awakenings that actually did occur.

It would be wonderful to have lots more comparative studies of religious events and phenomena that cross confessional and international boundaries.

I’ll have more to say about this topic next time.

SOME SOURCES

Before anyone notes this, I am aware that the literature on Convulsionnaires is diverse and often controversial, and each generation reconstructs the movement in its own image. See Anne C. Vila, “Shaking Up the Enlightenment: Jansenist Convulsionnaires and their Witnesses in Mid-Eighteenth Century Paris,” in Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics 41 (2021): 9-37; and Anne C. Vila, “The Convulsionnaires, Palissot, and the Philosophical Battles of 1760,” Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture 48 (2019): 227-243.

I have cited Brian Strayer’s Suffering Saints: Jansensists and Convulsionnaires in France, 1640–1799 (Sussex Academic, 2008). See also B. Robert Kreiser, Miracles, Convulsions, and Ecclesiastical Politics in Early Eighteenth-Century Paris (Princeton University Press, 1978). There is an excellent collection of texts in Catherine Maire, Les convulsionnaires de Saint-Médard: miracles, convulsions et propheties a Paris au XVIIIe siècle (Paris: Gallimard/Julliard, 1985).

For Jansenism, see a great many works by Monique Cottret, including, most recently, her Histoire du jansénisme (Perrin, 2016). For a valuable comparison of Pietism and Jansenism, see Dale K. van Kley, “Piety and Politics in the Century of Lights,” in Mark Goldie and Robert Wokler, eds, The Cambridge History of Eighteenth Century Political Thought (Cambridge University Press, 2006), 110-146.

Particularly for the later period of Jansenism, see the collection of essays edited by Mita Choudhury and Daniel J. Watkins, Belief and Politics in Enlightenment France: Essays in Honor of Dale K. Van Kley (Liverpool University Press, 2019).