I have been writing about how empires spread and shape religions. The most obvious feature of that process, perhaps, is in matters of language. Empires diffuse languages, which commonly survive after those empires themselves have faded into oblivion. In turn, transnational or global languages make world religions possible.

The Ghost of the Old Roman Language

The most famous example of that process is the role of Latin in the growth and diffusion of Christianity, especially in its Roman and Catholic form. Before the Roman Empire, the Mediterranean world had a great many languages and language families, most of which have vanished, in some cases leaving little trace. That includes, for instance, the Punic of North Africa and the Celtic languages of much of Continental Europe. There would also have been many other tongues not related to known groups, of which Basque is a very rare survivor today. When the Empire collapsed in the West, Germanic languages spread widely and rapidly. Under the Roman Empire, Latin spread far and fast, and eclipsed those older languages, at least among elites. In some cases, the lack of a vernacular written traditions accelerated decline and disappearance. When the barbarians arrived, they found a Latin speaking world.

Christianity spread within those linguistic boundaries, and took Latin with them. Usually, vernacular languages borrowed heavily from the new conceptual world, and its technical phrases. Latin had episcopus, which the ever cloth-eared English turned into “bishop.” That hegemony was all the greater when, as so often happened, Christian missionaries brought not only the faith, but the literacy through which it was expressed.

For a thousand years, Latin was the critical language of Christian life and thought in the West, with the Vulgate Bible as a primary vehicle. Of course, there was scholarly writing in vernacular languages – Irish, English, Russian, Icelandic, and others. But these were incidental to the larger religious story. Christianity spread Latin, and Latin spread Christianity. Right up till modern times, Latin was a key language in the religious life of Catholics, who long outnumbered their Protestant and Orthodox rivals.

As Thomas Hobbes noted of the Catholic Church in 1651, “The Language also, which they use, both in the Churches, and in their Publique Acts, being Latine, which is not commonly used by any Nation now in the world, what is it but the Ghost of the Old Roman Language.”

Christianity’s Other Tongues

As I say, that is a familiar story, but it is by no means the only example of its kind. Greek, of course, was the original primary language of Christianity, and the vehicle of so much of its thought and belief. For so many believers, the Scriptures meant the Greek Septuagint. But the enormous spread of Greek was a product of empires, especially the Hellenistic realms that inherited the world of Alexander the Great. It was two empires especially, the Seleucids and Ptolemaic, which brought so many cultures around the world into contact each other, and allowed the transcontinental spread of ideas and writings, not to mention visual imagery and iconography. The Septuagint itself was a product of Ptolemaic Alexandria, a city named for the original world-conqueror.

When the Roman Empire divided into western and eastern halves in the fourth century, Greek increasingly flourished, and gradually became known as “the Roman tongue.” Byzantine historians lamented barbarian attacks on their own land, which they called “Romania.” After the schisms with the Catholic world, Rhomaios came to be the term for an Eastern Orthodox Christian, who presumably spoke Greek.

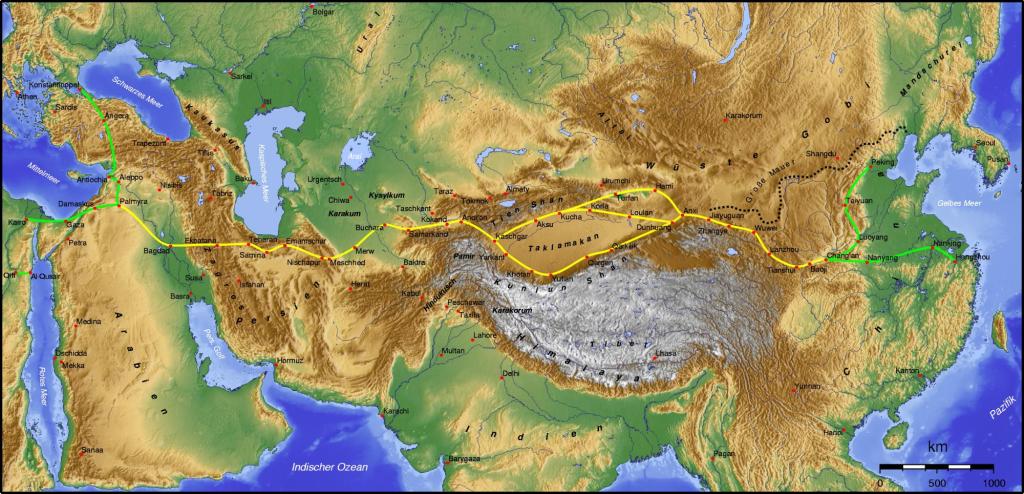

Another of the great historical languages of the Christian faith was Syriac, which originated in the Levant. It was the enormous Persian empire that allowed Syriac-speaking Christians to travel across so much of Central and eastern Asia, taking with them their scriptures and liturgy. As in the West, when the empire perished, the religious and linguistic ghosts persisted, and prospered. Syriac texts crossed the Silk Road, and are found in oases in China’s far West.

The ghosts in this case are those of the bygone Persian Empire. I’ll have a lot more to say about this issue in future posts.

The Language of the Horde

Nor is this a Christian story alone. It very much applies to Islam, which spread together with Arabic, often to cultures that were highly literate in older languages. Persian especially was a major rival. Over time, Arabic dominated, and today, some 400 million people speak Arabic as a first or second language. That does not include the other Muslims who must read and know the Qur’an in that language, even if it is not part of their daily life. Islam spread Arabic, and Arabic spread Islam.

Of their nature, empires bring together peoples from very different backgrounds and language environments, and makes them communicate with each other. Sometimes, those peoples might borrow the conqueror’s language intact, but often they mix and match, mingling old and new, and in the process, they create whole new languages, which go on to enjoy phenomenal success. Empires, in other words, create new languages, which serve as crucial vehicles for the building and spread of faiths.

Much like Latin in the West, those Islamic languages, Arabic and Persian, interacted with other tongues. One of the great languages of modern Islam is Urdu, spoken by over 200 million in the Indian sub-continent, if we include native speakers and those with a good working knowledge. The language is very much an imperial legacy – in fact, the heir of multiple empires, both Islamic and Christian.

Urdu is a version of the Hindustani language, but with extensive Persian and Persianized borrowings. Those additions reflect the activities of successive Islamic invaders and imperial conquerors from the north-west, particularly during the Mughal period. By the early eighteenth century, it came to be known as “the language of the camp,” Zaban-e-Urdu, using a Turkic word that found its way into English as “horde.” We might say that Urdu is “the language of the horde.”

Urdu became a highly sophisticated literary language with a vibrant poetic tradition. In an Islamic context, Urdu was the language of popular religious poetry, and of sermons. It became the key vehicle for modern-day Islamic revivalism. In the nineteenth century, it became the language for the vital schools of Islamic thought based in the subcontinent, the Deobandis and the Barelwis. The Deobandi school gave rise to many modern Islamist movements. A Deobandi scholar once told me, quite proudly, “It’s odd more people haven’t heard of us! We made the Taliban.”

The language enjoyed its greatest success and distribution because it was adopted as the standard tongue of the East India Company (in 1837), and subsequently of the British Raj. If British administrators and soldiers could not speak excellent Urdu, they had no place in the government of the sub-continent. Right up to the 1940s, it was a serious insult for an Indian to address an administrator in English, as it suggested that the Brit in question had not taken the trouble to learn good Urdu.

Imperial Britain borrowed extensively from Urdu, importing a great many of its words into the regular English language. As so often through world history, armies are commonly the means by which languages spread across empires, through a process of two-way transmission. Just to take a well known example, the British army wore uniforms that were “soil-colored,” or in Urdu, khaki.

In the First World War, British soldiers overseas famously wanted to get back to their home country, to Blighty. Soldiers prayed quietly for a “Blighty wound,” something not serious enough to kill or maim permanently, but enough to get them sent back home to peace and safety in Blighty. What word could be more English, more suggestive of village greens and the local pub? Blighty is however taken from the Urdu word bilayati, which in turn comes from the Arabic wilayat, meaning a country or kingdom.

Although by no means all Urdu-speakers today are Muslim, Urdu is the official language of Pakistan, and is very common among Indian Muslims. Respectively, Pakistan and India are the world’s second and third largest Muslim nations by population.

The Language of the Coast

East Africa offers a parallel story. In this region, Muslim traders from the Arabian Peninsula mingled with the Bantu-speaking Africans, where they created a hybrid language which in Arabic was called “of the coast,” Sawahili. Today, some twenty percent of the vocabulary of this Swahili language is made up of Arabic loanwords. At least a hundred million speak the language.

This area of East Africa was never part of a formal Caliphate or Empire run from Arabia or Baghdad, but the imperial influence was apparent in language and religion. We think of comparable regions beyond the old Roman frontiers, such as Ireland. I quote Wikipedia:

From their arrival in East Africa, Arabs brought Islam and set up madrasas, where they used Swahili to teach Islam to the natives. As the Arab presence grew, more and more natives were converted to Islam and were taught using the Swahili language.

When the European empires arrived, so they in their turn tried to appropriate its use. So did Christian missionaries. Swahili today has a very substantial tradition of Christian hymn-writing.

Language in Modern Africa

In modern times, we see a comparable mingling of religion and imperial languages, especially in post-colonial Africa. Back in the 1960s, when Christianity was rising in Africa and Asia, Western observers imagined that it would be expressed chiefly in local languages. Liturgical churches prepared services in those languages, and with appropriate adaptations of local custom and belief. It was all part of inculturation. I insert here a story about how Pope Francis began Advent a couple of years ago, with a Congolese Mass:

The Congolese (originally Zairean) rite was started by the Congolese bishops in 1969 after the Second Vatican Council, and is an adaptation of the Roman rite. It was approved by the Congregation for Divine Worship in 1988, and uses dance, oral stylistic traditions, songs with traditional instruments and invocation of the saints and ancestors of upright hearts.

Much of that was relevant and useful, but what those observers missed was just how critical the colonial languages would remain after independence, especially in societies with multiple local tongues. That meant English, but also French and Portuguese in their former empires. This is particularly apparent in the vast culture of revivals and miracle crusades, which use those old colonial languages as a means of crossing local ethnic and tribal boundaries. Why use multiple simultaneous translators when you can just use English? That also has the effect of making English (or the other European-derived tongues) seem like the normal means of communication in faith. Nigeria is a prime example of that process.

By the way, Nigeria has been an independent state since 1960, and the median age of its population is around 18 – that is, people born in this present century, and after 9/11. Only the really old have the slightest recollection of the British Empire, or of English as the language of imperial administration. For most Nigerians (or Ugandans, or Kenyans), English is an African language, and always has been.