“Evangelical Protestants have been debating for years over the definition and usefulness of the ‘evangelical’ label,” wrote Ryan Burge yesterday at Christianity Today. “Now, it appears ‘Protestant’ may be losing its place too.”

Both a political scientist and a Baptist pastor, Burge has become a uniquely helpful expert for me to follow in recent years, as he blends statistical analysis with personal experience to explain changes in American religion. His new book on the “religious nones” is an ideal introduction to that increasingly significant phenomenon, and his Twitter feed regularly provides intriguing snapshots of religious trends.

For the new CT article, Burge drew on Nationscape, a relatively new weekly survey conducted by the Democracy Fund and UCLA. When asked about religion, Christian respondents can opt either to identify either by that general term or choose a more specific label: Catholic, Protestant, Orthodox, or Mormon.

Most strikingly, Burge found that “Protestant” is becoming less and less popular with younger Americans, while “Christian” continues to grow. For example: while 70-year olds are about three times as likely to call themselves Protestant (33%) as Christian (10%) when given the choice between the two terms, almost the reverse is true among 20-year olds (22% Christian, 8% Protestant). The gap isn’t quite so large among people my age, but I’m still relatively unusual as a self-described Protestant in his mid-forties.

In some respects, that I still think of myself as Protestant shouldn’t be surprising. I’m also white and highly educated, two categories of Americans that Burge found to be more likely to keep using the term. (Younger African Americans, for example, are both more religious than their white peers and more prone to opt for “Christian” over “Protestant.”) I’m an evangelical who attends a mainline church, which makes me doubly attentive to differences and similarities within Protestantism. And as a history professor at a Christian college, I spend a lot of time helping young Americans who insist that they’re “just Christian” understand how much particular traditions and communities have shaped their religious beliefs and practices.

(Among the other problems Burge noted with the decline of “Protestant,” churches may struggle with the fact that “many folks sitting the pews may not have any clue about their church’s denominational affiliation or its connection to larger church history.”)

But I’m also on record here as suggesting that some older religious categories are less and less useful to describe American Christianity in the 21st century.

So why hold on to “Protestant”?

It’s not because I’m certain that Protestantism is the purest or truest form of Christianity. Indeed, I suspect that one reason for the decline of the term is that it evokes troubling memories of a time in church history when Christians were more likely to regard each other as heretics, rather than “separated brethren” who simply believe in, worship, and serve the same God in different ways.

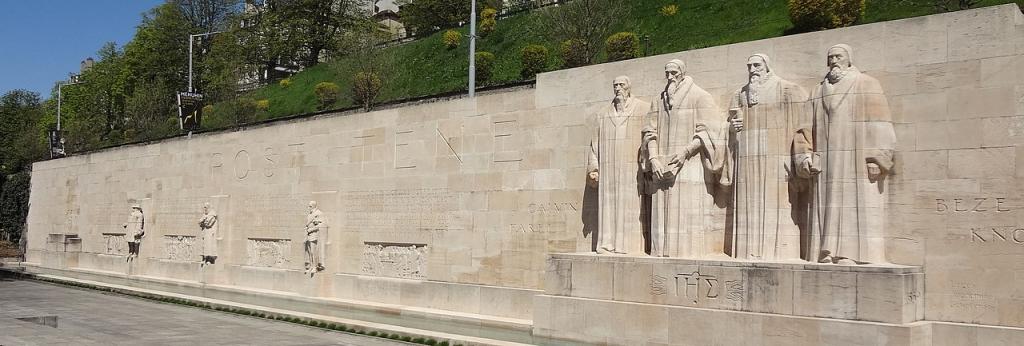

I come to my Protestantism by way of Pietism, an ethos that’s historically been more ecumenical in instinct than some of its religious cousins. But I still recognize differences in my way of following Jesus that trace back to the Protestant Reformation. And for all my uneasiness about extending the divisive legacies of that religious revolution, I still affirm its lingering influence on my identity.

That influence starts with theological doctrines, though they’re not the most important source of my sense of what it means to be a Protestant. I believe that I am a sinner saved by God’s grace alone and justified by faith alone, but I’m a sufficiently Melanchthonian Lutheran to believe that human will is freer than Luther allowed… and I’m a Pietist in part because I don’t want to neglect cultivating the fruits of faith for the sake of scorning “works-righteousness.” I believe in only two sacraments, but I can appreciate the value of continuing to confirm adolescents, to marry and to ordain adults, to bless the sick and dying, and to practice spiritual disciplines that help us identify and address the sin in our lives. (And the fact that I think of baptism and communion as sacraments sets me apart from many other Protestants, including the Baptists who employ me.) I believe in a common priesthood, but know that lay Catholics and Orthodox are as likely to be active members of their communities as Protestant pastors are prone to take on too much responsibility and power in theirs.

So I see my Protestant self less clearly in confessions and catechisms than in histories of Protestantism. Writing to mark the 500th anniversary of Luther’s 95 Theses, for example, Alec Ryrie defined his subject not in terms of the solas but the affections:

From the beginning, a love affair with God has been at the heart of [Protestants’] faith…. Beneath all the arguments, the distinguishing mark of a Protestant is the feeling and memory of that love, one on which no church or human authority can intrude. It is because Protestants care so deeply about God that they have been willing both to fight one another and take on the world on his behalf.

I don’t know that that kind of love is unique to Protestantism, but it seems distinctive of it. More than any doctrine or denominational membership, it’s that “love affair with God” with which no authority can interfere that makes me feel connected to Luther and his followers, who reminded the Catholic reformer Erasmus of “young men who love a girl so immoderately that they see their beloved wherever they turn…”

But most often, I see my Beloved in the one authority all Protestants are prepared to accept (and debate): the Bible. Without discarding the wisdom of tradition and the guidance of teachers, the acumen of reason or insights gained by personal experience, I join my spiritual forebears in turning to a book that they called “an altar where we meet the living God,” scriptures whose unchallenged authority John Calvin said (in a passage quoted by Ryrie) was “self-authenticating… a feeling that can be born only of heavenly revelation. I speak of nothing other than what each believer experiences within himself.”

Finally, I’m a Protestant because I protest. Not often, not too loudly, and never without doubt and regret, but I’m a Protestant because I find myself wanting to protest against Protestantism itself, which is as likely to fall into corruption, error, and torpor as anything else that humans do. To be Protestant is to recognize that no human interpretation of the Bible, even our own, is the same thing as the Word of God and that no human institution, even our church, is the same thing as the Kingdom of God.

But I protest in anticipation more than anger, trusting that any church once reformed will always be reforming. If Protestantism leaves me suspicious of what humans like me do in the name of God, it also leaves me hopeful for what God can accomplish through us sinners, whether we call ourselves Protestant or not.